I wrote recently about the year 1453, which marked the Fall of Constantinople, and therefore one of the most often cited events in European history. I suggested, however, that it mattered far less than we usually think. Realistically, historians can’t avoid using significant dates: textbooks, courses, and documentaries have to start and end somewhere. The problem arises when we take those dates of convenience and assume that they really did mark moments of fundamental change. Often, these were critical turning points for some people, but by no means for everybody.

Through the years, I have often taught courses on the History of the Second World War, which according to the original course description (which I did not create) is defined as running from 1939 through 1945. When the war started is open to some debate. Depending on where you stand, the conflict dated from the start of the Spanish Civil War in 1936, or the Japanese aggression in Manchuria in 1937. As I taught the class, I regularly placed so much emphasis on the continuities from the First World War – political, but above all, military – that the two great struggles came close to merging into one. In modern-day Russia, the approved Putin line sees the real war as only beginning in June 1941, with the Soviet-German confrontation, and everything before that “Great Patriotic War” was just squabbling between rival bands of equally malignant imperialists. The Battle of Britain? What’s that?

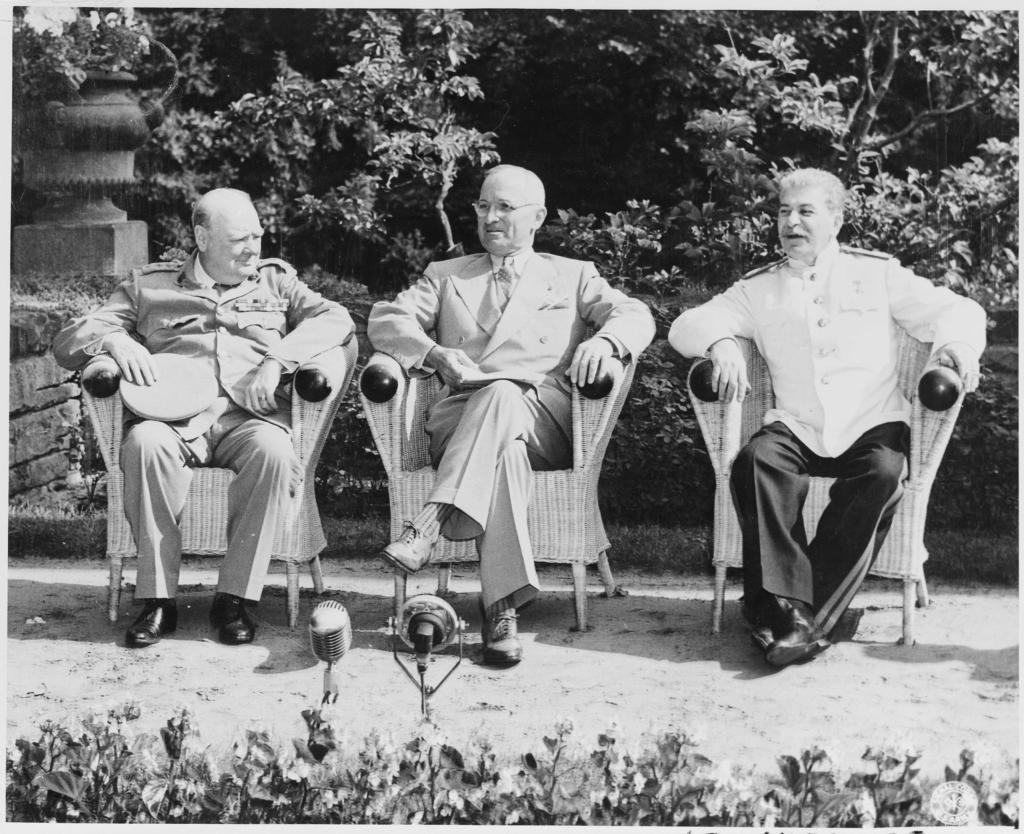

But surely, at least we can agree that 1945 marked the end of the war? Over several days in early May of that year, various German forces surrendered to Allied commanders, and we can celebrate the exact day of victory as we choose. But how do you get a symbolic ending more convincing than Hitler’s suicide in the bunker and the Soviet capture of Berlin, followed by Hiroshima and the Japanese surrender on the USS Missouri? We can hear the inspiring music as the closing titles roll. 1945, peace, demobilization, the boys come home, blue birds over the white cliffs of Dover… Most dramatically, and unequivocally, we know that this year marked the end of the Holocaust. Of course, we know that the Cold War was just starting off, but that is a whole different story, and one that would not hit its stride fully for a little while.

But that contrast between World War and Cold War is far more nuanced than we might think. We might think, for example, that the Second World War was a struggle against Nazis, Fascists, and ultra-nationalists. But in the crucial period between 1939 and 1941, the Soviet Union was de facto allied with the Axis. In the Fall of 1940, the time of the Battle of Britain, Stalin had come close to full membership in that group.

The “end” of the war is just as complex. Viewed from on high by aliens unfamiliar with the niceties of our familiar ideologies, it would be very hard to support this vision of a sudden shift to peace in 1945. In much of the world, including the familiar zones of combat over the previous few years, we really do not see any significant diminution in the scale of politically motivated violence and slaughter, nor of mass ethnic cleansing, and the scale of that violence is stunning. Just how many people died in warfare and political massacre in the post-1945 decade? Fifteen million? More? And in every case, these were conflicts that grew directly out of the great Second World War, or at most had been submerged temporarily during that struggle.

Look for instance at Keith Lowe’s bitterly depressing book Savage Continent: Europe in the Aftermath of World War II (2012), roughly covering the years 1945-1950. He describes the mass expulsion of twelve million Germans from Eastern Europe, which constituted the largest refugee crisis in human history. Two million of those Germans died in the process. That does not count a great many more Europeans – both fighters and civilians – killed in border wars and endemic massacres in the shifting borderlands between Poland and Ukraine. Meanwhile, anti-Communist guerrilla wars continued in Poland, the Baltic states, and the Ukraine through the mid-1950s. For Ukrainians, 1945 marked a new phase in a sequence of spasmodic wars, massacres, and persecutions that lasted intermittently from 1917 through 1956, nearly forty years in a wilderness of terror. From this perspective, the year 1945 itself marked at most a realignment of forces.

The era finds a grim symbol in the Sachsenhausen concentration camp in Germany, run by the Nazi regime from 1936 through 1945, where thousands were starved and murdered. From 1945 through 1950, Sachsenhausen was the site of the main concentration camp run by the Soviet NKVD in Germany, where thousands more were starved and murdered. The Communists likewise repurposed the former Nazi site of Buchenwald, with similar results. Meet the new boss. Same as the old boss.

That is all quite separate from the Greek civil war of 1944-49, which killed around 160,000 out of an original population of just seven million. I find it hard to pin down comparable figures for Yugoslavia in the same period. The country lost a million in the “actual” war between 1941 and 1945, and probably hundreds of thousands more over the following couple of post-1945 years of “peace.” 1945 made precious little difference to the factions involved, or even the uniforms they wore.

One reason we pay so little attention to the “wars after the war” is that so many of the victims were not European, and not white. The bloodiest theater of all was China. Between 1945 and 1949, the civil war between Nationalists and Communists killed at least 2.5 million. Communist victory was then followed by the bloodiest single phase of the era, when the government exterminated “landlords” and real or supposed class enemies. Estimates for the number of victims vary widely, but two or three million is a good estimate for actual killings. Millions more suffered prolonged imprisonment in conditions where survival was questionable. When we recall the notoriously genocidal Cambodian Communist regime of the 1970s, the Khmers Rouges, we often forget how closely they were following this original Maoist Chinese playbook.

Although it falls outside my chosen time period here of 1945-55, Communist China then went on to set a startling record even for the blood-soaked twentieth century, when famines induced by Mao’s Great Leap Forward (1958-62) killed somewhere between 15 and 50 million more Chinese people. Thirty million is a good consensus figure.

Going back to the immediate post-World War II period, other parts of eastern Asia also suffered ghastly violence, in the Indonesian Revolution (1945-49), the First Indo-China War (1946-1954) and of course the Korean War (1950-1953). Counting military and civilians combined, this phase of the Indo-China war alone killed at least a million. Korea accounted for three or four million dead, a large majority being civilians. Not so immediately connected to wartime conditions was the Partition of India in 1947, which killed many. Estimates range from perhaps 500,000 to ten million, with two million a reasonable consensus figure.

When set aside such unimaginable atrocities, something like the First Arab-Israeli War of 1948 looks very minor indeed, with “only” 25,000 dead.

If we take the number of deaths for 1945-1954 at a very rough fifteen million, that is about as many as perished during the whole First World War. For me, that arithmetic raises serious issues about the importance we attach to 1945, which in much of the world marked not an end to warfare, but at best a reconfiguration, even a rebranding. But our need for a clean narrative demands that we find a terminus for the “war years,” and that by definition means imposing a vision of “peace” on the subsequent decade, which in reality was horrendously destructive. To adapt the words of Patrick Henry, historians may cry, Peace, Peace — but there was no peace.

A case can be made for tracing the “History of the Long Second World War” from 1936 through about 1954. In terms of teaching, that post-1945 period demands far more than a token final class in a 15-week course on the Second World War – which in practice, is the very most that it ever receives.

On a related subject, the centennial commemorations of the First World War produced several important studies focusing on the “post-war” world of 1918 through 1924 or so. Even more than in the case of 1945, we readily see that 1918 not only did not mark the coming of peace, but in many parts of the world, the year marked a real turn towards the seriously bloody and destructive. Few would deny that the Russian Civil War grew inexorably out of the earlier struggle. To the total of those killed in action in multiple military conflicts, military or civilian, we add the vast numbers who perished in war-related famines, and the diseases that grew directly out of those famines, especially typhus. Everyone knows about the great influenza pandemic of these years, but typhus alone killed several million in the immediate post-war period – in Russia, Ukraine, Poland, Romania …. That is several times the number of all the battle casualties of the Somme and Verdun combined.

Viewed this way, the “Long First World War” of 1914-1924 killed more than twice as many as the narrowly defined events of 1914-1918. In this instance, the vast majority of those “additional” fatalities were European. One great read on all this is Charles Emmerson, Crucible: The Long End of the Great War and the Birth of a New World, 1917-1924 (2019).

So no, really, neither 1918 nor 1945 deserves quite the obsessive focus that we sometimes accord them.