“The Fall of Constantinople is a personal misfortune that happened to all of us only last week.” Those are the closing words of an extraordinarily influential book written in 1973 that most readers of this site will likely not have encountered. The words perfectly illustrate the sizable mythology that gets attached to historical events and dates, and how they echo through later centuries, often in utterly unexpected ways.

Last time, I wrote about the conquest of Constantinople by the Ottoman Turks in 1453, and suggested that at the time, its historical significance was really not that momentous. Later generations have elevated that event in many different ways, according to their ideological and cultural needs at any given time, usually – though not necessarily – with a central focus on religious matters. I’ll be looking at some of these interpretations in coming posts.

My opening quote comes from a notorious work of fantasy fiction, The Camp of the Saints (1973), in which Jean Raspail explored the consequences of the global population explosion that was then such a major theme in public debate. Noting the enormous and growing disparity between the fertility rates of the white world and “the rest,” his dystopian novel imagined those beggarly Third World masses pouring west to swamp and conquer Europe and North America in an apocalyptic act of judgment and vengeance. The title is taken from Revelation 20:

And when the thousand years are expired, Satan shall be loosed out of his prison, And shall go out to deceive the nations which are in the four quarters of the earth, Gog, and Magog, to gather them together to battle: the number of whom is as the sand of the sea. And they went up on the breadth of the earth, and compassed the camp of the saints about, and the beloved city: and fire came down from God out of heaven, and devoured them.

Raspail’s book closes with the imminent conquest of Switzerland, the last haven of White Christian civilization in Europe, by the South Asian hordes, and it is at that moment that the narrator harks back to Fall of Constantinople.

For Raspail and his devotees, the Fall of 1453 is understood as the failure of a once mighty civilization to defend itself against the barbarous followers of alien and fanatical cultures, especially in matters of religion. In The Camp of the Saints, civilization falls not because of the might of the invader but rather through the weakness and self-hatred of the old elites. Particularly to blame for Western collapse are toxically progressive Christian leaders such as the (future) Pope and the World Council of Churches.

You have to know something about Byzantine history to appreciate just how thoroughly that past informs and guides Raspail’s imaginary future. His fictional heroes, who resist the tidal wave of Third World immigration, bear the names of the last warriors who stubbornly defended Constantinople in its dying days. Such is his courageous French officer Colonel Constantine Dragasès, whose name requires a little elucidation. The last Byzantine emperor, who died in battle in the streets of Constantinople, was Constantine XI, whose mother was the Serbian princess Helena Dragaš, and from her the emperor took his name of Constantine Dragases Palaiologos.

Another of the novel’s heroes is Captain Luc Notaras, whose name precisely echoes Loukas Notaras, the last “prime minister” of the Byzantine state, and the last commander of its navy. After the sultan Mehmed captured Constantinople, he reputedly had sexual designs on Loukas’s two young sons, but the family refused his attempts, for which they were all executed. Other characters, Crillon and Romégas, are named for soldiers who served against the Turks in the great Christian victory of Lepanto in 1571.

The Camp of the Saints has subsequently become something like a sacred text for the racist Right and for anti-immigration campaigners, who see the book’s visions being literally fulfilled in the “invasion” of Global North nations by the mass influx of migrants and refugees who overwhelm borders and swarm the seas. Raspail’s concerns were frankly racial, but later writers focused equally on religious threats. As they built on Raspail’s theories, they envisaged a Christian Europe that would be conquered and then supplanted by an Islamic Eurabia.

In 2012 French rightist Renaud Camus published his book The Great Replacement, which explicitly argues for the existence of a conspiracy to displace older white populations. In the epigraph to his book, Camus cited two modern-day “prophets,” namely Raspail, and British anti-immigration campaigner Enoch Powell. The rhetoric of Replacement became a central tenet of faith for white supremacy militants worldwide, and has been cited by mass shooters and terrorists. At Charlottesville in 2017, the Far Right slogan was “You will not replace us!” (alternatively, “Jews will not replace us!”). The terminology has become entrenched in Right-wing discourse. Just this past month, an Italian Cabinet minister warned that “the country risked undergoing ‘ethnic replacement’ due to its low birth rate and the arrival of thousands of migrants.”

Like Raspail, activists regularly return to the Fall of Constantinople. In 2019, Australian terrorist Brenton Tarrant slaughtered fifty Muslims in terror attacks in Christchurch, New Zealand. He left a lengthy manifesto which was also titled The Great Replacement. As analysts studied the document, many were puzzled at just how frequent were references to Turkish and Ottoman history, but this is natural enough given the common Rightist fascination with 1453. Tarrant warned Turks that

You can live in peace in your own lands, and may no harm come to you. On the east side of the Bosphorus. But if you attempt to live in European lands, anywhere west of the Bosphorus. We will kill you and drive you roaches from our lands. We are coming for Constantinople and we will destroy every mosque and minaret in the city. The Hagia Sophia will be free of minarets and Constantinople will be rightfully Christian owned once more.

Tarrant’s rifle and its magazines were inscribed with multiple references to historical struggles between European Christianity and Islam, indicating the bygone heroes he idolized. The details are instructive.

It would be quite feasible to compile a substantial book on the influence of the myth of “1453” on the modern Right, not just on racists and white supremacists, but also on mainstream conservatives who would absolutely reject racist assumptions. In this latter mainstream category, I place Victor David Hanson, a writer I admire on so many points, not least in his writing on military history – but not so much on this specific history/mythology. In his recent syndicated essay “Are We The Byzantines?” he warns,

An ascendant China seems eerily similar to the Ottomans. Beijing believes that the United States is decadent, undeserving of its affluence, living beyond its means on the fumes of the past – and very soon vulnerable enough to challenge openly…

Like the Byzantines, Americans gave up defending their own borders, and simply shrugged as millions overran them as they pleased.

Our once iconic downtowns, like end-stage Constantinople before the fall, are now dirty, half-deserted, dangerous, and dysfunctional….

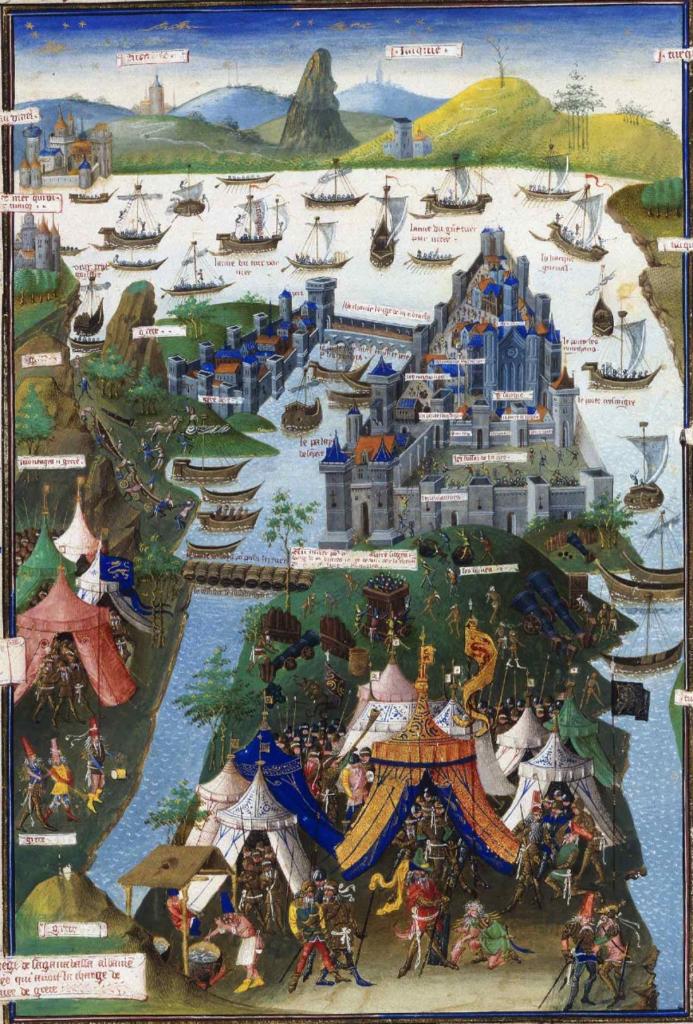

The article is illustrated by an early print representation of the Fall of Constantinople.

So to echo Raspail: yes, some years cast very long shadows, and later generations continue to live in them as if they happened yesterday. What was that line again? “The Fall of Constantinople is a personal misfortune that happened to all of us only last week.”

Also on Byzantine matters, I am happy to announce my forthcoming book A Storm of Images: Iconoclasm and Religious Reformation in the Byzantine World (Baylor University Press). Now available for pre-order!