Several months ago I took my first trip to the Jewish and Christian Holy Land. As I wrote in March, I entered the West Bank (Palestine minus the Gaza Strip) and Israel via the Jordanian border after spending over a week with family there. This is quite a different experience than the one shared by the vast majority of American pilgrims who fly into Tel Aviv and go through the standard amount of foreign air travel security and customs.

Crossing the Jordan

To enter the West Bank from Jordan, you cross over the King Hussein/Allenby bridge. To do that, you park in a dirt field and cross the street into a sort of compound that processes visas and customs. Then you board a bus to cross the bridge because you can’t cross over in your own car. This entire process involves showing your passport at least four times—and that’s just before you get to the other side.

Some context for all this rigmarole can be found in my experience touring the baptism site of Jesus on the Jordanian side the previous week. The welcome center displayed recent archaeological finds of ancient churches on the site—discovered only in the early 2000s! I thought that seemed awfully recent, and as I read along I learned why: the text of the sign said something like, “Before 1995, this was a war zone.” Ah.

Almost all of the people who cross the King Hussein/Allenby Bridge are Palestinians because many Palestinian families divided between the West Bank and Jordan after Israel won control of the formerly Jordan-annexed West Bank in the Six-Day War of 1967. My family were the only non-Arabs on the bus.

Whether by accident or design, all of the customs and security personnel I encountered on the Jordanian side of the crossing were men. And, the vast majority of Jordanian women wear hijabs. That means my first exposure to Israel/the West Bank was:

On the other side of the bridge, you are immediately greeted by women with machine guns and uncovered heads. The contrast could not be more stark.

What’s going on here is of course that all Israeli citizens, male and female, must do at least a two-year tour of duty in the IDF, the Israel Defense Forces. On this side of the crossing, you go through security and show your passport probably another four times or so for good merit.

To review, almost everyone who crosses this way is Arab, Palestinian to be specific, and almost all of the women wear hijabs. I am a white woman with uncovered very curly dark hair cut above my shoulders. And at some point I got separated in line from the rest of my American family. I am a Gentile, but I suddenly felt Jewish, even Israeli—because that is how I was likely perceived by everyone else in line. (A Jordanian friend confirmed this.) It was a fascinating experience: for a moment, I wasn’t “above” or “outside” the politics of the region, but within them.

Where Am I?

It was right after Christmas, so from there, we had a minibus drive us to Bethlehem, where we stayed at a guest house operated by Bethlehem Bible College, whose students are Arab Christians. To enter Bethlehem, you drive through a checkpoint with a sign that announces in Hebrew, Arabic, and English that you are now entering “Area A,” governed solely by the Palestinian Authority. You don’t have to show your passport, or even slow down, to drive into Bethlehem. The line to get back out is a parking lot.

This trip to the Middle East had been my first abroad for far too many years, so I wanted to know how many countries I was checking off. Definitely Jordan. But was my hotel room in the same country in which I set foot when I first crossed the border? And what country was that? One hour’s internet investigations later I concluded: it depends on what you mean by “country” and who you ask. This was maddening. I went to bed.

In brief, the West Bank is divided into Area A (several discontiguous areas, actually), governed solely by the Palestinian Authority (18%); Area B, governed jointly by Israel and the Palestinian Authority (22%); and Area C, governed solely by Israel (60%). Over two-thirds of the United Nations recognizes Palestine as a sovereign country. The United States does not, and I am a U.S. citizen. Palestinians travel under a “Palestinian Authority” passport that is not technically a national passport, but other countries agree to treat it like one. The border along the Jordan River is Area C. Bethlehem is Area A. Two days later we walked around Jerusalem.

Did I visit two countries or three during my trip? And on what days?

This complicated situation arose from a United Nations partition plan of the area into two states, Israel and Palestine, after World War II. The proposal attempted to solve two problems simultaneously: (1) Jewish people after the Holocaust needed a homeland, and Israel was its historic location. (2) Arabs had been living in that location for centuries. This was, and is, a nearly intractable conflict of interest. Local Jews accepted the plan, but Arabs did not. Surrounding Arab nations invaded the new state of Israel, and were defeated. Conflict has continued in various forms.

Christian Holy Sites

The next day, a wonderful guide took us to the major historical Christian sites in Bethlehem. Foreigners regularly ask him when he converted to Christianity, but his family converted about 700 years ago. He reported that prior to the establishment of the modern state of Israel in 1948, the majority of Bethlehem residents were Arab Christians. After the reshuffling of people that followed, the vast majority of Bethlehem residents are now Arab Muslims, but Arab Christians still own much of the property.

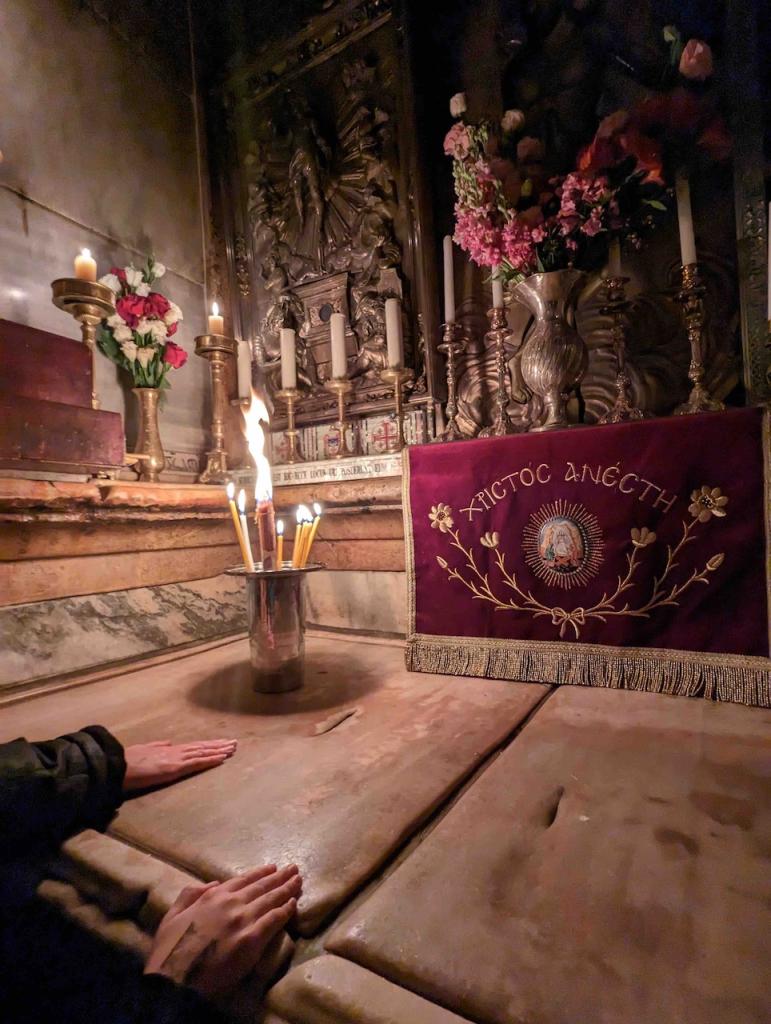

The main site for Christian pilgrims to Bethlehem is the Church of the Nativity. This church encloses the traditional site of Jesus’s birth, and I got to touch the ground there. As an Anglican, I tend to defer to the traditional locations, but you still never know. What is powerful for Christians is that, if not there exactly, somewhere nearby God touched the ground too.

Generations of church history have accumulated on the site and it no longer looks remotely like a place where animals were kept. Many of the traditional sites of key moments in Jesus’s life are jointly governed by the Roman Catholic and various Eastern Orthodox churches, with the mix of artistic styles that implies. The more Protestant one’s sensibilities, the more jarring this is. But what struck me was the diversity of human artistic creativity that Jesus’s life had called forth.

We had only three hours the next day to guide ourselves through the Old City of Jerusalem, so I researched which of two competing locations for Jesus’s crucifixion and resurrection to visit. The evidence suggests that the traditional sites, now enclosed in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, are more likely accurate. Meanwhile, the alternative sites better capture the feel of the original events because they are still in the open. Catholics and Orthodox tend to visit the former and Protestants the latter. Historian that I am, I convinced my family to go to the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, but I would love to return and visit the alternative sites as well.

After so many checkpoints, what struck me powerfully at the traditional site of the crucifixion and the empty tomb is that—barring the politics of getting into Jerusalem in the first place—the site itself has no security and is open to all. All who will come may. God welcomes everyone through Jesus.

The Western Wall

After the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, I wanted to visit the Western Wall. The Western Wall is what is left of the outside of the Second Temple area from Jesus’s day. Behind the wall, on the original site of the Jewish temple, the holiest site in Judaism, now stands Al-Aqsa mosque, the third holiest site in Islam. Which is to say, behind the Western Wall lies both the location of the Holy of Holies, what Jews and Christians believe to be the former particular dwelling place of the glory of God upon the Ark of the Covenant, and the Dome of the Rock, what Muslims believe to be the location from which Muhammed ascended to heaven.

As you might imagine, the politics of the site are complicated. Al-Aqsa mosque is governed by the Hashemites, the ruling family of Jordan, and that’s part of why they are the ruling family of Jordan. It does have considerable security. Jews can get permission to enter the mosque complex, but are forbidden from praying or displaying Jewish symbols. Palestinians, meanwhile, can find it difficult to get permission to enter Jerusalem at all. Most of the people on the Western Wall side are therefore Israeli Jews or tourists. It should be noted that this is turnabout: before 1967, Arab Muslims had forbidden Jews from entering that area and praying at the wall.

Signage in the Old City of Jerusalem is also a bit complicated and we ended up on an overlook rather than on the ground level of the wall itself. I had wanted to visit—and touch—the wall because at the sites of the birth and crucifixion and resurrection of Jesus, touching the places that God had touched in Jesus felt meaningful to me. Touching the closest location to the dwelling of God in the temple at Jerusalem felt like it would be meaningful too.

I looked over into the plaza in front of the Western Wall and thought, “Oh, good! There are actually openings right now. I could make my way down there and just be able to walk up and touch it.” And then I saw it: the openings were on the left, the men’s section, which constituted two-thirds of the site. On the right, the women’s section, the line was packed and seven-people deep across the entire wall. (Orthodox Jews manage the site, and practice strict division between men and women.) It was like every theater bathroom line during intermission. Only the problem with theater bathrooms is that male architects designed the men’s and women’s bathrooms the same size. Here the men’s side was actually larger.

And all of a sudden, my desire to touch the wall evaporated. My emotional response surprised me: most churches I have attended limit women’s opportunities more than men’s. Although I believe these restrictions arise from a misinterpretation of the Bible, I understand that they can spring from a well-motivated desire to adhere to what church leaders believe the Bible teaches. I am comfortable worshipping in these spaces and working to change minds that are open.

But this was the last site we visited on our trip, and I think I had encountered one too many walls. The dividing wall between men and women to visit the dividing wall between Jews and Muslims was somehow the final straw. And it wasn’t a distaste for either culture: I have long had a deep appreciation for Jewish culture and my trip to Jordan had given me a deep appreciation for Muslim culture as well.

What struck me in that moment was this: I had wanted to stand as close as possible to the location where God, who is omnipresent, had particularly dwelled in the Holy of Holies. But according to Christian theology, if none of the people at the wall or touring the mosque that day were Christians (admittedly unlikely), then the closest location of the particular presence of God to those standing at the wall was not in front of them, but behind them: the Holy Spirit indwelling me and my family members.

It hit me for the first time what an extraordinary claim that is. Christians believe that God dwells within believers in Christ in the same particular intensity that God inhabited the Holy of Holies. We are walking temples, bringing the presence of God with us, and charged to do so.

We are left with this paradox: Uniquely, Christianity asserts that God actually walked the earth in the person of Jesus in particular locations and not others. But Christianity is not a place-based religion in the same way as Judaism or Islam. The holiest site in Christianity is not the Church of the Nativity or the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, but any church: anywhere that those indwelt by the Holy Spirit gather to worship and celebrate the eucharist where Christ communicates himself to His people through the bread and the wine. And from there, anywhere a Christian walks out into the world.

May we live accordingly.

For Christ Himself is our peace, who made both groups [Jews and Gentiles] into one and broke down the barrier of the dividing wall….reconciling them both in one body to God through the cross, by it having put to death the enmity. -Ephesians 2:14-16, NASU