As a Cambridge undergraduate in the 1970s, my emphasis (major) was in Anglo-Saxon, Norse and Celtic, a peculiar product of that university. Essentially, ASNC was about the Dark Ages in the British Isles and Scandinavia from roughly 400 through 1100AD, studied from a broad interdisciplinary perspective, drawing on history, literature, languages, art history and archaeology. (By the way, scholars of the period hate the term “Dark Ages,” but I’ll use it here for convenience). The department now has a fun recruitment film on youtube.

I never for an instant regretted choosing that path, particularly since the group of professors I had at that time was utterly stellar. But the emphasis has posed some difficulties in later years when people want to know what I did at college: “You did what?” True, it does sound, um, abstruse. As time goes by, though, I realize that I could not have chosen a field better suited to my later scholarly career, or to some of the most significant hot-button issues in the study of Christianity. As I study global Christianity today, I still find insights from what I did all those years ago as an undergraduate.

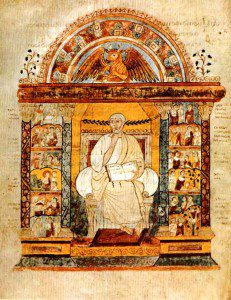

Inevitably, Christianity was absolutely central to studying the Dark Ages. The central fact of the era was the conversion of those regions to Christianity, which meant thinking about the nature of mission, and the relationship between old and new faiths. When for instance a formerly pagan society accepted Christianity, how much of their old ways should they retain? How many old customs or cultural forms could be brought within the scope of church life? Moreover, Christianity meant literacy: how did that transform the older society, and what scope did that allow for the old spiritual and cultural leaders, whether pagan priests or druids?

For many years now, my main area of research has been in Global or World Christianity, namely the historic shift of the faith’s center of gravity to the Global South, to Africa Asia and Latin America. In many instances, the issues at stake in this growth are very similar indeed to those of the Early Middle Ages. In Africa, for instance, Christianity boomed when it broke free from the constraints of the European missions, and developed a mass following among independent churches with native leadership. Often though, Western Christians were (and are) alarmed at what seemed to be concessions to old pagan ways, in matters like healing, exorcism and spiritual warfare. The debates resonate immediately with anyone familiar with Europe’s own conversion era.

Sometimes, the parallels between early and modern eras go beyond general similarities, and extend to traceable influences. In the year 601, Pope Gregory the Great wrote a famous letter to Abbot Mellitus, who was about to join the mission in south-eastern England. The Pope advised him about the proper treatment of pagan temples, once the people had accepted Christianity. He wrote, “that the temples of the idols in that nation ought not to be destroyed; but let the idols that are in them be destroyed; let water be consecrated and sprinkled in the said temples, let altars be erected, and relics placed there. For if those temples are well built, it is requisite that they be converted from the worship of devils to the service of the true God; that the nation, seeing that their temples are not destroyed, may remove error from their hearts, and knowing and adoring the true God, may the more freely resort to the places to which they have been accustomed. And because they are used to slaughter many oxen in sacrifice to devils, some solemnity must be given them in exchange for this, as that on the day of the dedication, or the nativities of the holy martyrs, whose relics are there deposited, they should build themselves huts of the boughs of trees about those churches which have been turned to that use from being temples, and celebrate the solemnity with religious feasting, and no more offer animals to the Devil, but kill cattle and glorify God in their feast.”

This advice was sane, pragmatic – and widely imitated. When Catholic clergy arrived in the newly conquered lands of Central and South America, they bore with them copies of Gregory’s letter, which shaped their response to the old native temples in that region. As in England, the process of converting buildings and festivities was wildly successful.

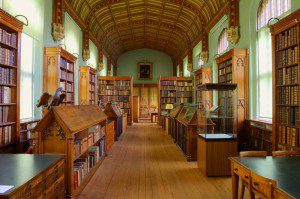

As Fernando Cervantes writes, “The works of Bede and Gregory the Great, for example, were widely available in Mexican libraries, and the famous letter of Gregory to Bishop Mellitus often cited. This gave rise to the widespread practice of erecting Christian churches on top of former pagan temples and of burying idols underneath new Christian altars. An illustrative glimpse of the process can be gained from a liturgical play entitled The Sacrifice of Isaac, performed in Nahuatl (the indigenous lingua franca of central Mexico) during the 1538 Corpus Christi pageant. From a modern perspective, it might be thought there was an obvious risk in having God demand the sacrifice of Abraham’s son on stage on the very feast day that commemorated the voluntary sacrifice of a human being whose broken body and spilled blood were to be sacramentally ingested. But this seems not to have bothered the friars. Inspired by the words of Gregory – “the Lord revealed himself to the Israelite people in Egypt, permitting the sacrifices formerly offered to the devil to be offered thenceforward to himself instead” – they built on indigenous notions and made a clear Christological link between the sacrificial son and the victim venerated on the feast of Corpus Christi. This was no isolated instance: barely a year later, the junta eclesiástica of 1539 stated that the situation in Mexico was “the same” as in Augustine’s England and Boniface’s Germany. Even after the narrowing strictures of the Tridentine decrees enforced a more cautious approach, the Dominican Diego Durán could still write enthusiastically about the idea of turning the sacrificial receptacles known as cuauhxicalli – literally “eagle basins” – into baptismal fonts: for “it is good that . . . what used to be a container of human blood, sacrificed to the devil, may now be the container of the Holy Spirit.”

Many scholars would see such an act of “conversion” in the Mexican cult of the Virgin of Guadalupe, who bears many feature of an Aztec goddess who was once worshiped on the site of her apparition at Tepeyac in 1531. Today, the Virgin is a central feature of Mexican religious life, and Pope John Paul II elevated her to the rank of Patroness of the Americas, both North and South.

Another fascinating parallel for me has been the relationship between old and new churches. In the Dark Ages – excuse the phrase – missionaries built new churches in Ireland and England, which soon went on to amazing cultural and spiritual glories. By the eighth century, these regions were sending their own missionaries to revive the moribund churches of Western Europe.

The children, in other words, outgrew the parents. In numerical terms at least, something similar is happening worldwide today, with the spectacular growth of churches in Africa and Asia, and these bodies are now sending their own missionaries to reconvert Western Europe.

Odd though it may sound, I could not have chosen a better foundation for studying the state of the world’s largest religion as it passes through one of the most revolutionary eras of change in its entire history.