I have been posting recently about the apocryphal gospels, remarking on their vast influence on the lived Christian faith over many centuries. The amount of modern scholarship on these “Other” gospels is immense, but I find one earlier historian makes some excellent points about just why these texts became as popular as they did. He also makes a massive contribution to understanding the Christian world on the eve of the Reformation.

Any history of modern Christianity notes the publication in 1863 of the epoch-making Life of Jesus by the French scholar Ernest Renan. Renan however also wrote a valuable History of the Origins of Christianity, which still repays study – and especially his chapter on the apocryphal gospels.

As he says, these gospels became so beloved because they so thoroughly captured popular tastes and interests, and moreover, served the aesthetic needs of artists and writers. He does a wonderful job of sketching their social and cultural impact in a very short space (Remember, he is spanning a thousand years!):

“Although of humble origin, and tainted with an ignorance truly sordid, the apocryphal Gospels assumed very early an importance of the first order. They pleased the multitude, offered rich themes for preaching on, enlarged considerably the circle of the evangelic personnel—St Anne, St Joachim, the Veronica, St Longinus—from that somewhat tainted source. The most beautiful Christian festivals—the Assumption, the Presentation of the Virgin—have no basis in the canonical Gospels; but they have in the apocryphas. The rich chasing of the legends which have made Christmas the jewel of the Christian year, is drawn for the most part from the apocryphas. The same literature has created the infant Jesus. The devotion to the Virgin finds there almost all its arguments. The importance of St Joseph proceeds entirely from them. Christian art finally owes to these compositions—very feeble, from a literary point of view, but singularly simple and plastic—some of its finest subjects. Christian iconography, whether Byzantine or Latin, has all its roots there. … The crib of Jesus without them would have lacked its most beautiful details. Their recommendation was their very inferiority [my emphasis]. The canonical Gospels were too strong a literature for the people. Some vulgar narratives, often base, were nearer the level of the multitude than the Sermon on the Mount, or the discourses of the fourth Gospel. So the success of these fraudulent writings was immense. From the fourth century the most instructed Greek fathers—Epiphanes, Gregory of Nyssa—adopted them without reserve. The Latin Church hesitated, even put forth efforts to take them out of the hands of the faithful, but did not succeed.”

The church’s hold became still weaker during the later Middle Ages, when paradoxically, repression actually made theologically deviant gospels even more popular. As society developed in wealth and sophistication from the twelfth century onwards, an ever-larger number of believers, clerical and lay, sought the right to read the Bible. The church reacted severely, forbidding vernacular translations for fear that heretical doctrines might creep in. That story is familiar enough. But the church’s ban on translation extended only to canonical texts, and not to – for instance – the Gospel of Nicodemus or the Infancy Gospel of Thomas. At a time when possessing a translated version of the canonical Gospel of Matthew could lead to a terrifying encounter with the Inquisition, no such problems arose with the wholly spurious Pseudo-Matthew.

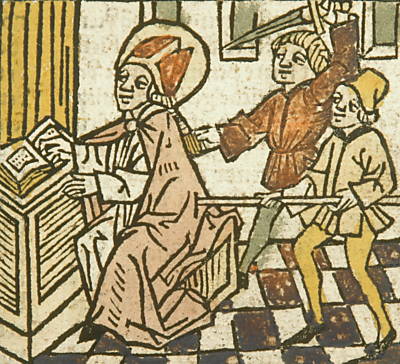

Renan notes the paradox: “In the Middle Ages the apocryphal Gospels enjoyed an extraordinary popularity; they have even an advantage over the canonical Gospels, which is this: not being a sacred Scripture, they can be translated into the vulgar tongue. Whilst the Bible is in a manner put under lock and key, the apocryphas are in everybody’s hands. The Miniaturists were ardently attached to them; the Rhymers seized upon them; the Mystics represented them dramatically in the porches of the Churches. The first modern author of a life of Jesus—Ludolphe le Chartreux—made them his principal document. Without theological pretension, these popular Gospels succeeded in suppressing, in a certain measure, the canonical Gospels.” [my emphasis]

Renan was broadly describing the period c.1200-1500 (Ludolphe wrote in the fourteenth century). In Western Europe, the apocryphal gospels and apostolic Acts achieved their greatest impact with the collection of stories and readings collected by Italian Archbishop Jacobus de Voragine about 1260, under the title of Legenda Aurea, The Golden Legend. This work was immensely popular, with hundreds of copies still surviving. In its day, it was Europe’s bestseller.

But before dismissing these texts as “medieval,” recall that these gospels enjoyed a new surge of popularity in the early years of printing, between about 1470 and 1530. If we just consider the Golden Legend, then it was in these years simply the book most often printed in Europe.

If you want to know what ordinary European Christians believed on the eve of the Reformation – including many sophisticated and educated believers – then turn to the farrago of bizarre tales and miracles of the Legend and the apocryphal texts it reports.

If anyone tells you that popular Christian fiction is becoming more popular than the Bible itself, don’t think that situation is anything new.