I am thinking of founding a Museum of Religiously Incorrect Art.

We presently live in a world of broad ecumenism and toleration: just think of reactions to the new Pope Francis. It’s instructive, then, to recall how much religious debate through the centuries has been so extremely confrontational and downright nasty, and this is especially true of conflicts within faith traditions. No church or denomination has any monopoly on this rhetoric. We think readily enough of the rich anti-Catholic tradition that has so often surfaced within Protestantism, but the traffic was definitely two way. (The Orthodox also have their own history, but that’s another story).

This was brought home to me recently when I visited Rome’s mighty church of the Gesù, mother church of the Jesuits. The order’s founder St. Ignatius Loyola is buried here, and his tomb is marked by two awe-inspiring sculptural compositions from the 1690s. Both were designed to be completed ready for the Holy Year of 1700. To the left of the altar, we see “Faith Defeats Idolatry,” which theme is uncontroversial enough (or was, until the rise of modern sensibilities).

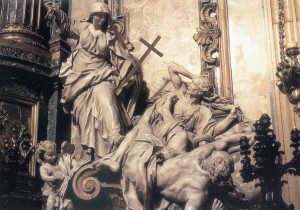

To the right, though, we are in much more problematic territory. Here we see Religion Overthrowing Heresy and Hatred, by the French sculptor Pierre Le Gros, the younger. Religion here is a vigorous and distinctly angry young woman, who through the cross subdues and defeats two figures – both older men. Beneath the figure of Heresy, a book bears Luther’s name.

Meanwhile, we see a putto, an angel, tearing pages out of books by Calvin and Zwingli.

Now, such a polemic is scarcely shocking when set beside centuries of Protestant depictions of the Pope as the Antichrist or the Whore of Babylon. But it is striking to see such venom specifically directed against the key Protestant Reformers. Incidentally, nothing in the church today draws the slightest attention to the controversial quality of these pieces: either you already know what they are, or you won’t find out.

It’s also a powerful reminder of just how late the Catholic Reformation could plausibly hope to win a global victory that would sweep away Protestantism once and for all. “Religion” (Catholic) is a young figure, while Heretical Protestantism is for the old and jaded.

Still by 1700, France’s Louis XIV was by far the most powerful European ruler, and the Habsburgs were steadily engaged in suppressing or expelling their remaining Protestant minorities. The great era of English world power was yet to begin.

In hindsight, we might think of the eighteenth century in terms of a North European Protestant hegemony that would soon become global in scope. At the time, though, Catholic hopes were still riding high, and plausibly so.