I posted recently about how the wide range of alternative gospels and scriptures disappeared from the Christian mainstream after about 400 – or rather, how they did not disappear. In reality, these Other Gospels were lost only in the sense that they dropped out of mainstream use for some churches, at some times, in certain parts of the world. The whole phenomenon really forces us to think about the nature of censoring or suppressing texts in early and medieval times – and even more, about the huge diversity of the Christian world.

The whole idea that non-canonical texts were censored or suppressed is grossly exaggerated. Clearly, if the orthodox Great Church had ever decided to grant canonical status to some alternative gospel – say, the Gospel of Thomas – then it would have achieved a global circulation, and would have become as much a core part of Western culture and art as did its more famous counterparts. But the fact that it was excluded from the canon did not in itself mean that the church suppressed or eliminated it, or that the church could have executed such a policy even if it so desired. Nor did such exclusion mean that an “alternative” text could not continue to shape religious consciousness. Plenty of non-canonical works have had an enormous influence on Christian belief and practice, and continue to do so.

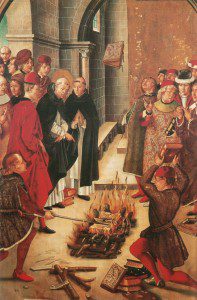

Undoubtedly, there were instances when particular church authorities did seek out non-canonical texts with a view to eliminating them altogether. To take one example from many, in 447, Pope Leo warned a Spanish bishop that “the apocryphal scriptures, which, under the names of Apostles, form a nursery-ground for many falsehoods, are not only to be proscribed, but also taken away altogether and burnt to ashes in the fire. … Wherefore if any bishop has either not forbidden the possession of apocryphal writings in men’s houses, or under the name of being canonical has suffered those copies to be read in church which are vitiated with the spurious alterations of Priscillian, let him know that he is to be accounted heretic, since he who does not reclaim others from error shows that he himself has gone astray.” Book-burning is no myth.

But the fact that a particular text is not familiar in the mainstream Western church tradition is not in itself evidence of censorship. If we look for instance at the abundant alternative texts that were created and circulated between the second and fourth centuries, the famous Gnostic Gospels like those rediscovered at Nag Hammadi, the great majority were in Syriac and Greek and circulated mainly in the eastern regions of the empire. They did not necessarily even appear in the increasingly confident churches of the Latin West, the ancestors of what would become the heart of later Western Christendom, so it is hardly surprising that they were not available to scholars in those regions.

But that emphasis on Western Christendom is significant. From the fourteenth century at least, Western Europe was the demographic and cultural center of the Christian faith, and that dominance only grew over the following centuries. Obviously, then, later scholars tend to look at European circumstances and assume they were the historic Christian norm.

In earlier times, of course, highly active Christian cultures had flourished across the Near East and northern Africa, which for long centuries had a good claim to stand as the intellectual centers of the faith. Catholics co-existed not only with Orthodox but also with deeply-rooted Nestorian and Monophysite churches. And often, these various bodies never lost access to an impressively broad range of non-canonical texts.

That diversity also reminds us of the near-impossibility of effectively suppressing a text across the whole polyglot Christian world, which at its height stretched from Ireland to China, from southern India into Siberia, from the borders of Kenya to the Arctic Circle. In only some of those areas did churches have the kind of close state alliances that would allow them to operate sweeping legal censorship. The kind of intrusive measures possible in, say, medieval France were out of the question for churches in Muslim-ruled Iraq or Egypt.

Just to take one example of survival among a great many, one popular ancient text was the Acts of the apostle Thomas. This was a second or third century Syriac work that early church leaders disliked intensely because it was so popular with various heretical groups. At first sight, then, it would seem a prime candidate for suppression. What happened though was that the work was so widely read that it was bowdlerized, cleaned of at least some of its heretical statements, but then allowed to run loose across the wider Christian world.

Apart from its early Greek and Syriac forms, the Acts of Thomas is known in multiple translations, including Arabic, Coptic, Georgian, Latin, Armenian and Ethiopic. It also served as the basis for the life of Thomas in the phenomenally popular collection of saints’ lives, the Golden Legend. The fact that it was not well known in the medieval Latin West does not indicate that the post-Nicene church had miraculously achieved a successful worldwide sweep of deviant texts.

So when you read about an ancient text being suppressed or eliminated by official action, ask yourself which institution could ever have had the power to achieve such a total act of annihilation. If we are told “the church,” then be sure to ask: which church? Where? When? And above all: How?

The whole story makes me think about Diarmaid MacCulloch’s new book on Silence in Christian History. Yes, the alternative gospel tradition seems to go silent for many centuries. But perhaps that’s because we aren’t listening properly!