I have been tracking the ancient “lost gospels” through the Middle Ages, when these alternative scriptures continued to exercise a remarkably wide influence. This was especially true in the cultures of Islam, which emerged in a largely Christian world fascinated by apocryphal writings. Even in the fifth century, Arabia was proverbially haeresium ferax: the breeding ground of heresies.

A century ago, Jesuit scholar Louis Cheikho stressed that the pre-Islamic Christian East was “literally inundated” with apocryphal works of both the Old and New Testaments (Quelques légendes islamiques apocryphes, 1910). He listed some of the influences that he could trace in the Qur’an itself: the Apocalypse of Adam [sic – actually the Life of Adam?], Book of Enoch, the Cave of Treasures, the Protevangelium, the Infancy Gospel of Thomas, the Arabic Infancy Gospel, and the Gospel of Barnabas.

Cheikho also warned that we should be very careful when reading Qur’anic citations to such seemingly familiar works as the Torah, the Gospel or the Psalms. In each case, he argued, we are not necessarily dealing with the canonical versions of these texts, but rather apocryphal versions or adaptations.

Not surprisingly, then, early Islam knew a great deal about Christianity and its writings, but not in forms accepted by the mainstream churches of either East or West. Both Jesus and Mary make frequent appearances in the Qur’an, but they are portrayed very differently from what we find in the canonical gospels. Some of these changes can be easily understood in terms of the establishment of a new faith – or, as Muslims, would say, the purification of an age-old faith. It is not surprising, then, to find the Qur’an’s Jesus affirming clearly that he is not God and shares nothing of divinity.

In other cases, though, we clearly see the signs of alternative traditions that originated within Christianity itself, and which were usually imported through apocryphal gospels. Such a source supplies the Qur’anic account of Mary, whose virginity is a tenet of faith for Muslims as well as Christians.

Mary’s life is described in the third Sura, Imran. Her mother prays for a child, and delivers a girl, who is promised to God. Mary is then raised in the sanctuary of the Temple, under the guardianship of Zechariah, where she receives her food miraculously, by divine gift. Zechariah then prays God for the gift of offspring, and the story then follows the canonical account of the conception of John the Baptist. We then return to Mary, to the angelic promise that she will bear a child, Jesus: “He will speak unto mankind in his cradle and in his manhood, and he is of the righteous.”

For a modern Christian reader, what stands out in this account is Mary’s “back-story,” the narration of who or what she was prior to receiving the angelic visitation. Medieval Europeans would however have recognized the tale immediately. Every one of the Qur’an’s statements is rooted in the second century Protevangelium, from the woman’s initial prayer for a child, to her pledging Mary to lifelong service to God, and Mary’s childhood in the Temple – where she receives food from the hand of an angel.

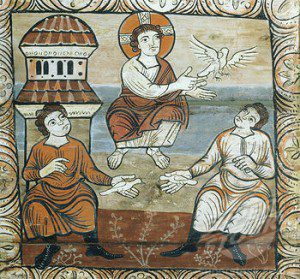

The Qur’an also recalls other episodes from Jesus’s life that are not in the mainstream Christian gospels. In Sura 5, al-Ma’idah, God calls on Jesus to recall the wonders he has wrought with divine power. Some are familiar enough to Christians, including healing the blind and lepers, but the verse proceeds: “Remember My favor to you and to your mother: how I strengthened you with the holy Spirit, so that you spoke to mankind in the cradle as in maturity; … and how, by My permission, you shaped the likeness of a bird out of clay, and blew upon it, so that it became a bird” (5.110).

Again, there is no mystery in finding the originals of these stories. The Arabic Infancy Gospel reports Jesus in his cradle telling his Mother of his divine identity and mission. The tale of the birds features in the Infancy Gospel of Thomas.

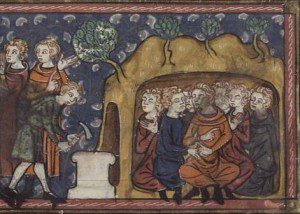

Other examples abound. The Qur’an also tells the story of the Seven Sleepers, youths miraculously preserved after being walled up alive in a cave (Sura 18.9-26). In its origins, this is certainly a Christian story, reported by the fifth century Syrian Father Jacob of Serugh, and well known throughout the European Middle Ages.

Apocryphal texts apart, the Qur’an drew on the ideas of non-orthodox Christian movements. On the crucifixion, the Qur’an declares, “They slew him not nor crucified, but it appeared so unto them; and lo! those who disagree concerning it are in doubt thereof; they have no knowledge thereof save pursuit of a conjecture; they slew him not for certain but Allah took him up unto Himself.” (4.157-58) That is pure Docetism, of a kind that had flourished for centuries in Christianity’s eastern regions.

We could find plenty of other examples. What is striking is that this abundance of apocryphal material is found within the Qur’an itself, even before Muslims occupied the Eastern Christian territories, and were still more intensely exposed to their writings.

In consequence, the Islamic world became a treasury of writings otherwise lost or suppressed in Latin Europe. But “lost” in one part of the world certainly does not mean lost altogether!