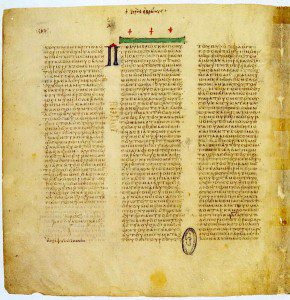

Any history of the New Testament text makes extensive use of the magnificent fourth century Greek Bibles, the “uncial codices.” We know the three greatest as Alexandrinus, Vaticanus, and Sinaiticus. These were splendid deluxe volumes intended for major churches, intended to be accessible to the Empire’s new Christian elites. They thus give an excellent idea of just what the Bible looked like like during the decades following the Roman Empire’s acceptance of Christianity.

Modern readers though might be surprised at just which texts these Bibles did include. While they obviously did not give space to controversial texts like the so-called Gnostic Gospels, they were significantly more inclusive than a modern Western translation like the New International Version.

In the Old Testament, these Bibles used the Septuagint, which is broader in its contents than the standard canon that we know today. This remains the Old Testament known to the Orthodox Church.

Although the manuscripts have substantial gaps, we can safely assume that all originally included the full roster of standard OT books. In addition, though, they all incorporated such Deuterocanonical works as Sirach (Ecclesiasticus), Wisdom, Tobit, Baruch, and Judith. Sinaiticus has four Books of Maccabees. Alexandrinus and Vaticanus have the Epistle of Jeremiah. Vaticanus has the full spectrum of the Deuterocanon, except for Maccabees and the Prayer of Manasseh.

The most complete Septuagint text is Alexandrinus. Over and above the Deuterocanon, this has 3 and 4 Maccabees, and Psalm 151. It also has the Fourteen Odes, a collection of Old Testament canticles and prayers, including the Prayer of Manasseh. The codex’s list of contents shows the Psalms of Solomon.

The New Testament collections contain some surprises. All would have had the standard canonical books known today, even with such controversial items as Revelation. That work is found in Alexandrinus and Sinaiticus. Although not now found in Vaticanus, it was probably present originally. In addition, though:

-Sinaiticus has the Epistle of Barnabas and the Shepherd of Hermas.

-Alexandrinus included the two Letters of Clement.

-Vaticanus does not have any such New Testament additions, but the manuscript as we have it is missing the pages where any such extras might have appeared, so we can only speculate.

Apart from their obvious historical importance, these Bibles suggest the lack of rigid uniformity in the definition of canon, so that stray texts like the Psalms of Solomon might still appear in the Old, or the Letters of Clement in the New.

More significant, they leave no doubt that most Christians still followed the Septuagint in its choice of canonical texts, with the Deuterocanonical books emphatically part of the mainline scriptures.

My own copy of the Septuagint was published in 1851 under the editorship of the splendidly named Sir Lancelot Charles Lee Brenton. He went to astonishing lengths to make sure that no faithful reader be misled into taking the Deuterocanonical texts as authentic parts of scripture. The book has the Old Testament, some 1100 pages, followed by several blank pages, so you are convinced the book is finished. But then, aha, we find a new title page and new table of contents, and only then, the Deuterocanonical books, here labeled the “Apocrypha,” which runs to a further 250 pages (mostly the four books of Maccabees). Metaphorically, the Deuterocanonical texts are fenced off by a moat with alligators.

This segregation is wholly strange to ancient Bible texts, notably the great codices that I am describing here. Those manuscripts offer no hint that these texts were anything other than fully-accredited Biblical books, and in no sense “apocryphal.”

Christians of the era of Ambrose and Augustine would have found most 21st century Bibles distinctly thin in their contents.