Throughout their history, Christians have used the Old Testament as well as the New. But their Old Testament references often derived from a much wider body of texts that we know under that name. Apart from the canonical books, many other works circulated purporting to expand on the stories found in the Hebrew Bible, and often under the name of venerated prophets or sages. Unless we appreciate the volume and influence and such texts, it is often hard to understand references in the works of mainstream authors, to say nothing of their influence in art and literature.

To understand just how much such alternative scriptures could diverge from familiar forms, look at the Epistle of Barnabas, a second century text that could easily have gained acceptance in the New Testament itself. (As it stands, it is listed among the Apostolic Fathers). At one point, the author refers to the story of Amalek, found in Exodus 17. Joshua has defeated this treacherous enemy, whereupon (according to the King James translation), “And the Lord said unto Moses, Write this for a memorial in a book, and rehearse it in the ears of Joshua: for I will utterly put out the remembrance of Amalek from under heaven” (Exodus 17.4).

For Barnabas, though, such a story is multiply significant. He knows that, in Greek, Joshua is the same name as Jesus, so that references to the Old Testament warrior must be understood in that later messianic sense. He thus reports the story in these words: Moses commands Joshua, “Take a book in thy hands and write what the Lord saith, that the Son of God shall in the last day tear up by the roots the whole house of Amalek.” (Barnabas 12.9, Kirsopp Lake translation).

Although Barnabas is notionally quoting the Exodus story, his citation has precious little in common with the original. He has moreover added a whole eschatological and messianic dimension that absolutely is not in the original. Although he might be inventing these words himself, it is also likely that he is transmitting a whole tradition of Christian midrash on the original Biblical texts.

Christians also drew on the pseudepigrapha, the works attributed to great figures of the Old Testament, to Abraham, Moses or Ezra. Many such works had originated from Second Temple Judaism, but Christian editors soon revised them to their own purposes.

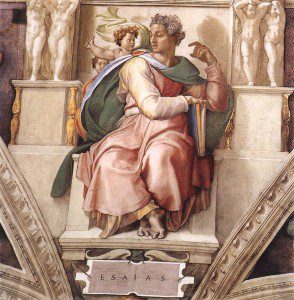

Isaiah was a very popular focus for such pseudonymous later works. The canonical Book of Isaiah was of course enormously influential in shaping Christianity, but other later works purported to give extra information about the prophet’s martyrdom and his ascension through the heavens. The Ascension of Isaiah probably dates from the second century AD, and both Jerome and Epiphanius quote it. Suggesting its wide influence, copies survive in multiple languages, including Greek, Latin, Coptic, Ethiopic, and Old Slavonic.

Although it was certainly not the only non-canonical best-seller of its kind, it does illustrate the great popularity of such writings over many centuries, among orthodox and non-orthodox alike. Such Visions, Revelations and Ascensions were so popular because they fulfilled popular demand for ever-more information about the spiritual geographies of heaven and hell.

Part of the Ascension circulated independently as the Vision of Isaiah, and as such it played a special role in inspiring dissident Christian movements. This was a prized text of Balkan Dualist movements like the Bogomils, and through them of West European groups like the Albigensians or Cathars.

The Vision’s appeal to Dualists is not hard to grasp. As Isaiah reports his successive visions in the heavens, it is obvious both that Satan is the Prince of the World, and that the world is the scene of constant warfare between supernatural forces of good and evil. As Isaiah reports, “And I saw there a great battle of Satan and his force, who were opposing piety. And one was vying with the other, because on the firmament it is just the same as on earth, for the images of the firmament are here on earth. And I said to the angel: ‘What is this warfare and vying and battling?’ And answering me, he said: ‘This warfare is the Devil’s, and it won’t cease until there comes the One whom you will see, and He kills him with the spirit of His power’.”

The struggle will end only with Christ’s triumph: “When He descends and will be in your form, the Prince of the World will lay his hands on Him, because He is [God’s] Son, and they will hang Him on a tree and kill Him, not knowing who He is. And He will descend to hell and will render naked and useless all those phantoms, and He will take prisoner the Prince of Death and will wipe out all his power.”

The importance of this Isaiah literature is beyond question, if we have any interest in the works that shaped the Christian mind through the early and medieval centuries. Yet it is also easy to see why it should escape the attention of non–specialists. Its notionally Old Testament setting would seem to make it relevant to scholars of the Hebrew Bible rather than of Christian literature, although its theology and message are both thoroughly Christian. We should in fact count works like the Vision of Isaiah as definitely part of the New Testament Apocrypha – a category that potentially can expand to considerable size!

And to stress once again a theme dear to my heart: that’s yet another example of a direct link between the fringe Christianity of the earliest era and the heretical dissidence of the High Middle Ages, a direct conduit from 200 to 1200 AD.