There is a passage in the Alexandrian writer Philo that casts a curious light on Christian origins, and I wish I understood it better. Let me put it out there for discussion.

Philo reports on the violent and confrontational politics of the Egypt of his day, particularly the 30s AD. Alexandria was sharply divided between Jewish and anti-Jewish factions. When King Herod Agrippa visited Alexandria about 40, the Jews showed their vigorous support for him. The anti-Jewish party, though, staged a bizarre demonstration to mock the king.

Here is Philo’s report:

There was a certain madman named Carabbas … this man spent all this days and nights naked in the roads, minding neither cold nor heat, the sport of idle children and wanton youths; and they, driving the poor wretch as far as the public gymnasium, and setting him up there on high that he might be seen by everybody, flattened out a leaf of papyrus and put it on his head instead of a diadem, and clothed the rest of his body with a common door mat instead of a cloak and instead of a scepter they put in his hand a small stick of the native papyrus which they found lying by the way side and gave to him; and when, like actors in theatrical spectacles, he had received all the insignia of royal authority, and had been dressed and adorned like a king, the young men bearing sticks on their shoulders stood on each side of him instead of spear-bearers, in imitation of the bodyguards of the king, and then others came up, some as if to salute him, and others making as though they wished to plead their causes before him, and others pretending to wish to consult with him about the affairs of the state.

Then from the multitude of those who were standing around there arose a wonderful shout of men calling out “Maris”; and this is the name by which it is said that they call the kings among the Syrians; for they knew that Agrippa was by birth a Syrian, and also that he was possessed of a great district of Syria of which he was the sovereign.

The rest of the political conflict is not too relevant here, except to say that the mob then tried to erect imperial images in the synagogues, provoking riots and pogroms.

But to return to Carabbas. Can anyone familiar with the New Testament read this story without thinking of the mocking of Jesus, reported in all four gospels?

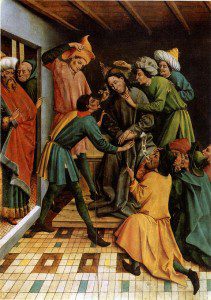

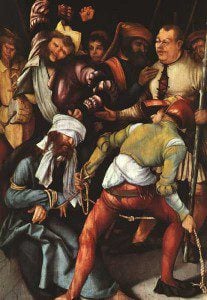

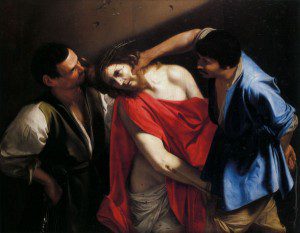

As Mark wrote,

And they clothed him with purple, and platted a crown of thorns, and put it about his head, And began to salute him, Hail, King of the Jews! And they smote him on the head with a reed, and did spit upon him, and bowing their knees worshipped him. And when they had mocked him, they took off the purple from him, and put his own clothes on him, and led him out to crucify him.

The stories are clearly different in many respects, and there are no obvious verbal resemblances in the original text. But the overall similarities are substantial. In both, we see the mocking of a pseudo-king, who is crowned with a pseudo-crown derived from a plant, and given the attributes of monarchy. Does Mark’s “reed” recall the “small stick of the native papyrus” given to Carabbas?

In both cases, the story has a Jewish-Semitic character, even though the Carabbas tale is set in Alexandria: they are mocking a Jewish king, or pseudo-king. The Alexandrian crowd shouted “Maris!”, Lord or King; the soldiers hailed the King of the Jews.

There is even a resemblance of sound. Although the names are linguistically unrelated, Carabbas sounds a lot like like Barabbas, who features so notoriously in the crucifixion story. In fact, the Barabbas story leads directly into the account of Jesus’s mocking.

Most strikingly, the two events occur within a decade of each other, and about three hundred miles apart.

Obviously, plenty of scholars have noted this parallel – I think of John Dominic Crossan, Vernon K. Robbins, Raymond Brown, and others – but it is still not widely known or discussed.

What is happening here? Philo assuredly does not know the gospels, which would not be written until many years after this. The Gospel writers show no dependence on Philo – although the Carabbas tale regularly shows up on websites presenting the silly case that Jesus was a wholly mythical being, created by lying evangelists.

Incidentally, Eusebius in the fourth century did discuss Philo’s account of these Alexandrian struggles, although he paid no attention to the Carabbas story.

I freely admit that I am speculating, but I offer two theories:

-One is that both events are strictly historical. However far-fetched it sounds, someone who had witnessed the death of Jesus happened to be in Alexandria a few years later, and suggested a near-identical parody as a means of discrediting Herod Agrippa, which the mob then adopted.

-Alternatively, both events, in Jerusalem and Alexandria, were wholly independent. In both cases, participants adapted a popular custom or ritual for the purposes of political satire.

We can argue what this custom might have been. I am almost embarrassed to note this, but in The Golden Bough, Sir James Frazer wrote about the creation of pseudo-kings who would fill the position of the real king for a day, before being sacrificed in his place. Such pseudo-kings were normally drawn from the most disposable sections of the population, beggars or criminals. Frazer argued, further, that the Jews practiced such mock-kingship, and that one of the king’s titles would have been Barabbas, “Son of the Father.” He also suggested that Philo’s Carabbas was a scribal misunderstanding of the real name.

Frazer is radically out of fashion, but we do know that the ancient world abounded in dramatized mysteries and rituals. Moreover, the idea of temporary pseudo-kingship is quite widespread around the world (and usually unrelated to any form of sacrifice). At special times, societies would declare periods when normal rules of behavior were suspended, and social hierarchies suspended, times of carnival and celebration like the Roman Saturnalia. These periods were placed under the symbolic rule of some kind of anti-king, like the medieval European Lord of Misrule.

Very tentatively, I wonder if some such ritual might have provided a format for both the “mocking” events I describe, in which a Jewish pseudo-king was held up to ridicule.

If that seems dubious, I really would be grateful for some other explanation of the truly odd parallels we see here.