Britain during the 1960s and 1970s suffered from a Prime Minister named Harold Wilson. Once, when Wilson was to read the lesson at Westminster Abbey, the clergy involved asked him which version of the Bible he would like to use – King James, Revised, which one? Flustered, Wilson supposedly replied that he would read from the Word of God.

That question of “which Bible” is actually more confusing that many Christians think. Around the world, the canon of the Bible varies substantially, in the New Testament, and often spectacularly in the Old. Now, it might be easy to dismiss the opinions of some ancient but tiny Oriental churches, but other bodies pose quite different issues.

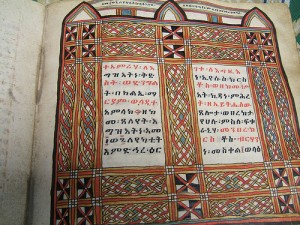

Of all the world’s churches, the one with the canon that differs most radically from the standard US Protestant version is Ethiopia’s truly ancient Tewahedo church, which commands the loyalty of some 45 million people. This is rather more than the number of all US Baptists of all denominations combined. Among many other distinctive features, the Tewahedo Old Testament includes Enoch and Jubilees – both truly bizarre works by the standards of mainline Western Christianity.

But we don’t have to travel to Africa or the Middle East to find quite different concepts of the Biblical canon. Today’s Protestant Bible would seem remarkably short to many Christians around the world, and indeed to past Protestant generations. In my next couple of posts, I’ll be discussing the implications of some of the books that have dropped out of memory in fairly recent times. Some of them really do deserve to be known and appreciated much more widely.

The main difference involves the so-called Second Canon, the Deuterocanonical books. As used in the Roman Catholic Church, these include such texts as Judith, Tobit, Wisdom, Sirach (Ecclesiasticus), 1 and 2 Maccabees, Baruch, and some additional passages in Daniel. These works were not formally included in the Hebrew Bible as fully canonical, although they had appeared in the Septuagint.

Different churches had accepted them from the early Christian centuries. Occasionally, some scholars would protest against their inclusion in the Christian canon – Jerome was hostile. But these critics admitted that they were in a small minority, and the church’s overwhelming consensus won out over time.

Even medieval Proto-Protestants like the Waldensians not only accepted and read these books, but seemingly treated them as among their favorite sections of the Bible. They loved stories like Maccabees and Tobit, and venerated the main characters as Christian role-models.

Modern Western Protestants may well have heard of these books, and think of them under the general title of “apocrypha.” For most non-Protestant churches around the world, though, they are not apocryphal, but fully accredited components of the canon, which are read in the liturgy. This is true of the Catholic and Orthodox traditions, as well as Oriental Orthodox, Armenian, Coptic and Ethiopian. If such matters were ever to be decided by raw numbers of Christians worldwide, then the Deuterocanon would win by something like a three to one margin. The Roman Catholic Church alone, by far the world’s single largest religious body, accounts for some 55 percent of Christians.

Just how Protestants came to lose these books is a curious story. Reformation-era debates over the Bible naturally focused on issues of canon. The Reformers naturally held to the most stringent standards of inclusion, which usually meant accepting the familiar Jewish definition of the Hebrew Bible. After some disagreement at the Council of Trent, Catholics fully accepted the Deuterocanon, a term coined in the 1560s by Sixtus of Siena. Although historical interpretations decided the two positions, Catholics also favored books favorable to their theology, and Protestants accordingly disliked these same works. One text in Maccabees, for instance, supports the idea of prayers for the dead.

But excluding books from the Protestant canon certainly did not mean abandoning them overnight. Most early Bibles did indeed include the “Deuteros,” but segregated in a special section of apocrypha, sandwiched between the Old and New Testaments. This was the solution of Luther (1534) and it was followed by the Geneva Bible, the standard English text for most mainstream Anglicans and Puritans alike for a century after its publication in 1560. (It was many years before the King James overtook it in popularity).

Church authorities were careful to stress that these books should not be taken as fully authoritative. In 1563, for instance, the 39 Articles of the Church of England listed these “other Books (as [Jerome] saith) [that] the Church doth read for example of life and instruction of manners; but yet doth it not apply them to establish any doctrine.” The Westminster Confession of Faith in 1647 was tougher still, declaring that “The books commonly called Apocrypha, not being of divine inspiration, are no part of the Canon of Scripture; and therefore are of no authority in the Church of God, nor to be any otherwise approved, or made use of, than other human writings.”

Even so, these texts were included in Bibles and were presented in exactly the same manner as the canonical books, in similar typeface and appearance. The books continued to have authority and religious significance, and the stories they told remained widely known. I could give countless examples, but let me take one English moment. In 1746, the Duke of Cumberland returned to London after bloodily defeating the Jacobite rebellion. Handel composed an oratorio for the occasion, and naturally turned to the Bible for an appropriate story of a heroic general fighting for his nation and faith against a pagan foe. Also, the story had to be a famous piece well known to a Protestant audience. Where else would he turn, then, but to the story of Judas Maccabaeus? Patriots of the American Revolution loved the story of Maccabees.

English-speaking Protestants lost the Deuterocanon not through any calculated theological decision, but through publishing accident, and at quite a recent date. Prior to the early nineteenth century, Anglo-American Bibles included the apocryphal section, but this dropped out as printers sought to produce more and cheaper editions. Increasingly too, during the nineteenth century, anti-Catholic sentiment encouraged Protestants to draw a sharp line between the two variant Bibles. If Catholics esteemed books like Maccabees and Wisdom, there must be something terribly wrong with them.

As I have noted elsewhere, the sudden loss of those books had unexpected consequences: “That timing meant that when Protestant missionaries set out for Africa and Asia, the Apocrypha did not feature in the Bibles they carried with them, and those texts never had much impact on emerging churches. Over time, though, new converts compared notes, and some were startled to find the disparity between Protestant and Catholic Bibles. On occasion, those converts became suspicious about the explanations that missionaries offered for the differences. Some asked whether their pastors were keeping whole parts of the Bible secret, presumably for their own selfish ends.”

For whatever reason, then, Protestants over the past century have tended not to know these works. Not only is the OT apocrypha missing from modern Protestant versions – above all, the NIV – it is not even a ghostly presence, in the form of an explanatory note. I have one NIV Study Bible that offers a couple of dismissive lines on why these books are missing. Seemingly, they contribute nothing to what we learn from the rest of scripture, and are historically wildly inaccurate – in contrast, say, to the still-canonical (and highly dubious) Esther.

These stories, then, have vanished from consciousness. Although modern Protestants very likely know the Maccabean story, it is almost always in the Jewish context, in terms of the origins of Hanukah. This is a critical distinction. Although Christians fully acknowledge the Jewish dimensions of (for instance) the Exodus or the Exile in Babylon, these stories have been fully integrated into the Christian narrative. Maccabees, in contrast, is now viewed as a Jewish scripture, and no longer part of “our own” Bible.

Similarly, when I consult my library catalogue for Margarita Stocker’s 1998 book on Judith (Judith: Sexual Warrior – Women And Power In Western Culture), the subject heading is “Judith (Jewish Heroine).” Generally, we don’t consign Moses or Isaiah to the category of “Jewish Religious Figures.”

The situation is almost Orwellian. Not only have these books dropped out of Bibles in which they once were included, but it’s as if they had never existed in the first place.

As I’ll suggest, that Protestant amnesia is a real misfortune. These books offer some real treasures.