In a number of recent posts, I have argued that long after the time of Constantine, Christians around the world continued to use and cherish alternative scriptures, some teaching ideas far removed from the established churches. Having said that, a time did come when many of those texts really were suppressed, more thoroughly than the medieval church or state ever could achieve.

So just what happened, and when?

The Reformation marked a critical point in the process. From the start of the sixteenth century, Protestant Reformers not only stressed the Bible as the sole source of authority in religion, but struggled to define exactly which books belonged in the Bible. It was at this point, for instance, that Protestants excluded the Deuterocanonical Old Testament books from regular use, designating them as apocryphal. Martin Luther himself would have gone further, and placed a number of New Testament works like the Epistle of James into this category of disputed books, the antilegomena.

This new Biblical emphasis reshaped the liturgy, the common means by which most ordinary people were exposed to scriptures of all kinds. In England in 1549, Archbishop Thomas Cranmer lamented what had become of the liturgy in recent years, suggesting how apocryphal and marginal texts had virtually taken it over: “These many years passed, this godly and decent order of the ancient fathers hath been so altered, broken, and neglected, by planting in uncertain stories, legends, responds, verses, vain repetitions, commemorations, and synodals, that commonly when any book of the Bible was began, before three or four chapters were read out, all the rest were unread.” The new church order demanded a stricter focus on the Bible.

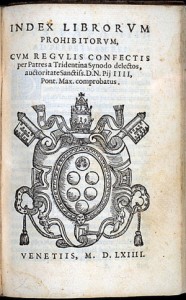

As Catholics struggled to reform their own church to meet the new challenge, they too drew sharper lines between approved and unapproved scriptures. They also suppressed some of the more outrageous cults and devotions to saints, and the texts on which these were based.

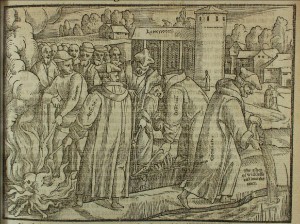

New technologies ensured the effectiveness of these new policies. In the Middle Ages, little prevented the copying of manuscripts, however incendiary their contents. In the new order, though, books were printed, and governments worked long and hard to regulate the output of printing presses. If an old manuscript account failed to make it into circulation as a printed book, its contents were unlikely to survive.

These new attitudes created a much chiller atmosphere for once popular texts like the Golden Legend, which right up through the 1520s had been one of the most popular books in Europe. Both Protestants and Catholics showed themselves determined to downplay flagrantly non-canonical works, both in their own right and as part of collections like the Legend.

This is important for our present discussion, as the Legend was the vehicle by which Europeans knew the substance of so many ancient apocryphal works, especially the lives of the apostles. “Reformers” broadly defined (both Protestant and Catholic) made the Legend the target of their zeal, using it as a symbol of everything wrong with the late medieval church. Gold, indeed! The rector of the Sorbonne called it the Iron Legend, while Spanish theologian Melchior Cano said it must have been written by a man with an iron mouth and a heart of lead.

Protestants were even harsher, and mocked the outrageous miracles attributed to saints. Denouncing the Legend, Luther complained that ” ‘Tis one of the devil’s proper plagues that we have no good legends of the saints, pure and true. Those we have are stuffed so full of lies, that, without heavy labor, they cannot be corrected. …. He that disturbed Christians with such lies was doubtless a desperate wretch, who surely has been plunged deep in hell. Such monstrosities did we believe in Popedom, but then we understood them not. Give God thanks, ye that are freed and delivered from them and from still more ungodly things.”

Across Europe, older works like the Legend and many apocryphal stories were not so much abolished as discarded, as they had become so utterly unfashionable.

I would also add one point that is all too easy to forget, namely that the Christian world of 1520 (say) was far smaller in geographical scope than it had been five hundred or a thousand years earlier. In 1000, the Roman church had had no say whatever in what Christians did in Egypt or Persia or India, and there were a great number of Christians in those parts of the world. In the fourteenth century, the number and power of those non-European Christians had shrunk dramatically, and Ottoman Muslim power stretched deep into Europe itself. To take just one example, the ancient heresy of the Bogomils now vanished, possibly as surviving adherents merged into the newly triumphant power of Islam.

If it did not actually disappear, “non-European Christianity” was a pale shadow of its former self, and the remaining Christian world was much easier for the mainstream church to control. At least before the Protestant schism, the Roman Pope was now the sole independent church head remaining, with the Eastern Patriarch a puppet of the Ottoman sultan.

Finally, Catholic powers now began their march to global empire, and they whipped into conformity many of the surviving remnants of those once-glorious non-European churches. In the process they destroyed any suspect scriptures they found.

I’ll describe this grim story at great length in my next post.