I was discussing the theory that the oldest level of Egypt’s Christianity was very different from anything we would recognize as orthodoxy, and that the most prominent leaders were what we would call Gnostic. That theory can be advanced in extreme terms, so that basically there is no early orthodoxy. Even if we do not go that far, we certainly find plenty of Gnostic teachers and groups in early Egypt, and they are influential.

That Gnostic term is of course controversial today, and scholars often put “Gnosticism” in quotes, as it suggests that these ideas were somehow radically distinct from Christianity, almost a different religion. However foreign or bizarre the ideas might seem to a modern Christian audience, they shared the same roots, growing out of a common inheritance – Christian, but especially Jewish.

Generally, Gnostics taught a process of Creation, emanating from absolute perfection, and descending to lower levels of reality. These systems and the names used varied enormously between individual teachers. The common theme though was that the material world we know is the creation of an inferior spiritual being, who is also the God described in the Old Testament. Christ came from higher spiritual realms to redeem and enlighten the sparks of true divinity that survive within the pollutions of matter.

In the first half of the second century, Egypt produced several of the earliest and most influential Gnostic teachers, Basilides, Valentinus and Carpocrates. I’ll focus here on Basilides.

In the 120s, Basilides taught a complex system of Creation and unfolding degrees of reality. One supernatural figure, the Great Archon, wrongly believed himself to be the ultimate God, forgetting or ignoring the higher spiritual levels, and this is the divine figure we know from the Old Testament. The world we know is a deeply flawed creation, combining the bungling errors of the Archon with some sparks of divinity from the spiritual heights.

These superior beings sent messengers to illumine and redeem the world, and also to teach the Archon his error. One of that exalted elite was the Aeon known as Christ, who descended on Jesus at his Baptism, and remained with him until the Crucifixion. The Christ of the Gospels thus taught absolute truth, but the material Jesus was only his vehicle.

As Irenaeus wrote around 180, describing the views of his heretical opponents:

Those angels who occupy the lowest heaven, that, namely, which is visible to us, formed all the things which are in the world, and made allotments among themselves of the earth and of those nations which are upon it. The chief of them is he who is thought to be the God of the Jews; and inasmuch as he desired to render the other nations subject to his own people, that is, the Jews, all the other princes resisted and opposed him. Wherefore all other nations were at enmity with his nation. But the father without birth and without name, perceiving that they would be destroyed, sent his own first-begotten Nous (he it is who is called Christ) to bestow deliverance on them that believe in him, from the power of those who made the world.

He appeared, then, on earth as a man, to the nations of these powers, and wrought miracles. Wherefore he did not himself suffer death, but Simon, a certain man of Cyrene, being compelled, bore the cross in his stead; so that this latter being transfigured by him, that he might be thought to be Jesus, was crucified, through ignorance and error, while Jesus himself received the form of Simon, and, standing by, laughed at them. For since he was an incorporeal power, and the Nous (mind) of the unborn father, he transfigured himself as he pleased, and thus ascended to him who had sent him, deriding them, inasmuch as he could not be laid hold of, and was invisible to all.

Incidentally, that view of the crucifixion as illusion is one that would be long popular in the eastern Christian world, and it found its way into the Qur’an.

Here is Irenaeus again:

Those, then, who know these things have been freed from the principalities who formed the world; so that it is not incumbent on us to confess him who was crucified, but him who came in the form of a man, and was thought to be crucified, and was called Jesus, and was sent by the father, that by this dispensation he might destroy the works of the makers of the world. If any one, therefore, he declares, confesses the crucified, that man is still a slave, and under the power of those who formed our bodies; but he who denies him has been freed from these beings, and is acquainted with the dispensation of the unborn father.

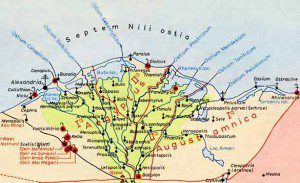

According to the fourth century historian Epiphanius, Basilides also took his message outside Alexandria proper, into the Delta, in “the districts of Prosopitis and Athribis; not but that he also visited the district or nome of Sais and Alexandria and Alexandreiopolis.” Basilides still had followers in the fourth century, although his movement was eclipsed by later Gnostic teachers.

Although Basilides’s religion diverges so massively from any Christian orthodoxy, he certainly located himself in Christian tradition. He claimed to have received his teachings from Glaucias, an interpreter of St. Peter, and also claimed a special tradition from the apostle Matthias. In other words, Basilides was boasting an alternative apostolic succession.

Also, he was one of the very first to write commentaries on the New Testament, in his now vanished Exegetica (although recent scholars like James Kelhoffer would play down this contribution).

Basilides also left his mark on other movements that continue today. I adapt the following from a piece I wrote for CHRISTIAN CENTURY:

In the ancient Christianity of Ethiopia, by far the greatest celebration of the year is Timkat, which marks the Baptism of Christ, and the Epiphany. The event draws pilgrims in their millions. But why? I suggest that the commemoration recalls a time when Jesus’s followers had a special veneration for the Baptism, which some believed marked the moment when Christ received his divinity.

In the second century, we know that Basilides’s followers had a special veneration for Jesus’s Baptism, which they celebrated on January 6. This was the date at which God became manifest – in Greek, the time of Epiphany. The mainstream church appropriated the festival easily enough, as the lines between orthodoxy and heresy were not too strictly defined in Egypt at this time.

In light of those origins, let us look again at the Ethiopian Timkat. Although most of the church’s earliest records have been lost, we know that Ethiopian Christianity was flourishing by the fourth century, and that it has always had a very close relationship with the church of Egypt, and especially Alexandria. Not surprisingly, then, Ethiopia keeps alive very early Egyptian interests and obsessions, even some that might have been forgotten in Egypt itself. Whatever the church’s official theology says, Timkat recalls a very old and somewhat heretical interpretation of Christ’s baptism and its significance.

If you want to see Timkat at its most spectacular, then go and see the celebrations in Ethiopia’s great royal city of Gondar.

Gondar, by the way, was built in the seventeenth century by a great Ethiopian emperor who bore the auspicious name of Basilides.