I recently described the extraordinary position that Egypt held in early Christian history, when the country became the source of many ideas and institutions that would spread throughout the wider Christian world. Given that importance, it is really surprising that we know so very little about the early history of Egyptian Christianity, an ignorance that really demands explanation.

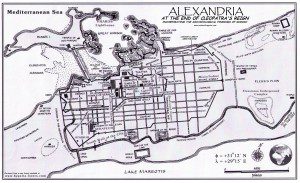

As I wrote, its very strong Jewish presence means that Egypt must have been a very early center of Christian expansion. Late in the second century we start to hear of Alexandria as the base for many major religious and cultural figures. Pantaenus, for instance, headed Alexandria’s great catechetical school, while Clement of Alexandria was his celebrated pupil. Origen’s great era was soon to come.

But what about the earlier years, between say 30 and 180? Our only reliable source is Eusebius, who knows next to nothing beyond a tradition that Mark was the first bishop. He cites the names of some successors, but they remain that, only names. In the tenth century, historians tried to collect the biographies of the various patriarchs, and the material on Late Antiquity is dazzlingly rich. Before 180, though, there is nothing worthwhile beyond what we find in Eusebius. Of the second century bishop Cerdon, all we read is that “He was chaste, humble and innocent throughout his life,” which can charitably be described as filler.

Partly, this may be because the early Alexandrian patriarchate was collective, so that the bishop would have worked closely with a kind of committee of priests, but even so it is odd that no individual really makes an impression. (Later Presbyterians loved to cite that Alexandrian precedent!)

Also, prior to the early third century, we have no accounts of martyrdoms.

So where are the early Christians? Who exactly is copying and reading all the second century gospel texts that turn up from time to time in the Egyptian desert? We have a couple of names, but Apollos in Acts is the only celebrity. Why is Alexandria in 120 or 160 not producing its local counterparts of Ignatius, Polycarp and Irenaeus? Alexandrians were not famous for being humble or self-effacing.

A couple of solutions come to hand. One is that the earliest Christians were firmly located within the Jewish community, which suffered appallingly during the wars and massacres of the late 60s, and again in Trajan’s time, 115-117. Perhaps the Christian minority took a particularly long time to recover momentum after this debacle, while many early records and documents had been destroyed.

One scholar, though, offered an alternative solution to this mystery. In 1934, Walter Bauer published the still-provocative Orthodoxy and Heresy in Earliest Christianity, challenging the familiar view that “Great Church” orthodoxy had always been the Christian mainstream, while “heresy” bubbled up sporadically at its fringes. No, said Bauer, originally Christianity was extremely diverse, and radically different variants dominated different regions. In some areas, what we call Catholic orthodoxy was itself a fringe cult. In Edessa, Marcionism was so strong that the orthodox were a tiny sect labeled the Palutians.

Only gradually did orthodoxy spread throughout the Christian world, suppressing and displacing older variants. Retroactively, the Catholic/Orthodox rewrote history to make it look as if they themselves had always enjoyed mainstream status, and writing their old enemies out of the picture.

Bauer’s thesis has been much criticized through the years, and few scholars today would accept his work without qualifications. He did overclaim, and he bent every available piece of evidence to fit his argument. He also omitted texts that failed to fit his theory. Even so, his basic idea still intrigues, and nowhere more so than in Egypt.

Bauer’s view, simply, was that Egyptian Christianity in the first and second centuries was a flourishing enterprise, but it was overwhelmingly Gnostic in character. That is going too far. But the faith in Egypt looked very different from later orthodoxy, with much more of a slant to Jewish Christianity and extreme asceticism as well as to Gnosticism.

If so-called “mainstream” orthodox Christianity existed, it was strictly marginal. Even Apollos, a heroic figure in the New Testament, originally followed a version of faith that knew only the baptism of John. If we believe the Western Gospel text tradition, then he had learned his doctrine “in his own country,” namely Egypt.

What little we know about the so-called Gospel of the Egyptians shows that it was strongly anti-material and anti-sexual, preaching an asceticism that condemned sex and reproduction. At the end of the second century, Clement of Alexandria quoted it, “the Savior himself said: ‘I came to destroy the works of the female’. By female he means lust: by works, birth and decay.” Around 150, Justin Martyr reports an Alexandrian Christian who sought official permission to castrate himself. A half-century later, Origen did just that.

Matters eventually changed only with daring figures like Clement himself, who taught a “Christian gnosis.”

If Bauer was right, then Egypt did indeed have its famous Christian leaders in the second century, but they preached doctrines that would ultimately be relegated to the far fringes of faith. If Basilides and Valentinus really were the most significant leaders of what Egypt knew as Christianity, then the early Christian world was a very diverse place indeed.

By the way, there is an excellent account of these movements, and the debates surrounding them, in Birger Pearson’s Gnosticism, Judaism and Egyptian Christianity. Also useful is C. Wilfred Griggs, Early Egyptian Christianity.