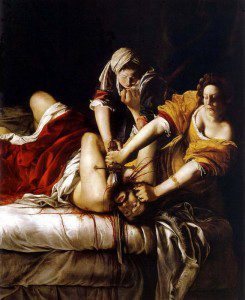

Some months back I described how the Bible’s Deuterocanonical books had inspired so many artists through the centuries. I particularly mentioned the wonderful Baroque artist Artemisia Gentileschi (1593-1656), who among other things was celebrated for her gory portrayals of Judith beheading the enemy general Holofernes.

The Wall Street Journal recently did a piece on a new exhibit of her work, centered on that Holofernes story. (Subscription required for access to the WSJ site). Kyle MacMillan describes the efforts of the Chicago Art Institute to bring the painting from Florence’s Uffizi Gallery for an exhibition on “Violence and Virtue” that runs through January 9.

It’s striking to see how her work has been rediscovered from modern times:

Five decades ago, Gentileschi’s canvases lay forgotten in museum basements. But starting in the 1970s, she became something of a feminist icon, her riveting life story grabbing the popular imagination and helping to make her more famous than some of her once better-known male contemporaries.

According to many writers, the extreme brutality of the painting draws on her own personal experience. As the exhibition website notes,

At the age of 18, she was raped by one of her father’s colleagues, Agostino Tassi. He was convicted in a trial a year later after Artemisia was tortured to “confirm” her testimony, but Tassi was never punished. Within months of the conclusion of the trial, Artemisia was quickly married and moved to Florence with her new husband. The brutal depiction in the monumental Judith Slaying Holofernes is often interpreted as a painted revenge for the rape. Unlike other artists who focused on the ideals of beauty and courage evoked by the Jewish heroine Judith, Gentileschi chose to paint the biblical story’s gruesome climax, producing a picture that is nothing short of terrifying. As the heroine decapitates Holofernes, the general of King Nebuchadnezzar, to save the Jewish people, her brow is furrowed in concentration, her forearms are tensed, and blood spurts wildly from her victim’s neck.

The painting testifies starkly how readily artists could deploy religious and Biblical stories to explore the most unsettling and uncomfortable themes.