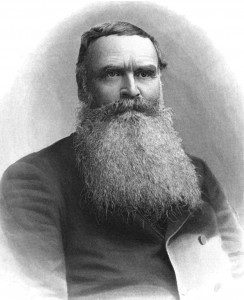

In 1866 William Taylor, a renegade Wesleyan evangelist from the Appalachians, arrived in the south of Africa. A tall six feet with a long, scraggly beard that draped down over a barrel chest, Taylor was “a Methodist preacher of the old school.” He was “adept at charming his hosts, delivering folksy sermons, deflecting opposition, spinning humorous anecdotes, and promoting his own ministerial exploits.” When he came over to South Africa, Taylor unleashed a wild style of revival that featured improvisation and length. His extra long (and exuberant) services lasted until 10 p.m., instead of 8 p.m. A young Boer observer condemned the “blasphemous proceedings in this town” and the “outrageous proceedings.” But many others were not repelled. Within a couple of months, over 600 Mfengu and Xhosa peoples converted.

In 1866 William Taylor, a renegade Wesleyan evangelist from the Appalachians, arrived in the south of Africa. A tall six feet with a long, scraggly beard that draped down over a barrel chest, Taylor was “a Methodist preacher of the old school.” He was “adept at charming his hosts, delivering folksy sermons, deflecting opposition, spinning humorous anecdotes, and promoting his own ministerial exploits.” When he came over to South Africa, Taylor unleashed a wild style of revival that featured improvisation and length. His extra long (and exuberant) services lasted until 10 p.m., instead of 8 p.m. A young Boer observer condemned the “blasphemous proceedings in this town” and the “outrageous proceedings.” But many others were not repelled. Within a couple of months, over 600 Mfengu and Xhosa peoples converted.

On one hand, say some scholars, the revival could be understood as the culmination of decades of work by British missionaries who preceded Taylor. On the other hand, the revival seemed to come out of nowhere. Why there? Why then, after three futile decades with very few converts to show for their efforts? The straightforward explanation is that Taylor, a American Wesleyan missionary, did it. Taylor himself certainly crowed about his successes. The Anglican bishop, he reported, had only baptized “two babies” while “my Zulu and his black legion, and I, with my pale face,” had converted “over 320 whites, and over 700 natives.” This success, he said , stood “in refutation of the skepticism and infidelity of the times.” His practice of a full-orbed supernatural faith based in the holiness tradition seemed to work much better than the rational disenchantment practiced by the British missionaries.

In An Unpredictable Gospel: American Evangelicals and Global Christianity, 1812-1920, Jay Case tells a  third version that credits British missionaries a little, Taylor some, and a third character a lot. Charles Pamla was a Mfengu convert who had read John Wesley’s sermons in 1853 and had prayed for entire sanctification in early 1866. In early May he received this second blessing, which he described as “different kinds of thoughts, ease from the world and from all the cares of the flesh.” Within days, Pamla had converted over 100 in an area around a mission station at Annshaw in modern-day South Africa. Only then did Taylor arrive, whereupon the two evangelists paired up. By July, they together converted over 600. Hardly any observers, Case writes, “would have dreamed that in a space of several months, an Mfengu evangelist would be instrumental in producing more converts than scores of British missionaries had managed in the half-century before. They also would have found it hard to believe that Charles Pamla was better equipped than they were for the task. After all, the missionaries were better schooled in theology, had more years of Christian experience, and embodied the qualities of a nation know for its advanced civilization.”

third version that credits British missionaries a little, Taylor some, and a third character a lot. Charles Pamla was a Mfengu convert who had read John Wesley’s sermons in 1853 and had prayed for entire sanctification in early 1866. In early May he received this second blessing, which he described as “different kinds of thoughts, ease from the world and from all the cares of the flesh.” Within days, Pamla had converted over 100 in an area around a mission station at Annshaw in modern-day South Africa. Only then did Taylor arrive, whereupon the two evangelists paired up. By July, they together converted over 600. Hardly any observers, Case writes, “would have dreamed that in a space of several months, an Mfengu evangelist would be instrumental in producing more converts than scores of British missionaries had managed in the half-century before. They also would have found it hard to believe that Charles Pamla was better equipped than they were for the task. After all, the missionaries were better schooled in theology, had more years of Christian experience, and embodied the qualities of a nation know for its advanced civilization.”

The revival worked, argues Case, because Taylor and Pamla empowered indigenous Christian leaders. In contrast to political officials, educators, and mainline missionaries trying to civilize the heathens, Taylor validated Xhosa tradition. He read books about Xhosa history and culture. He used African names for God. He contended that African tribal laws against murder, stealing, adultery, and lying were remnants of the biblical commandments. He encouraged translation of the biblical texts into indigenous languages. He preached side by side with Pamla, who also set up meetings between Taylor and Africans to talk about indigenous cultural practices. Taylor encouraged the spiritual practices of the Xhosa, who liked to shake and cry aloud during worship. And perhaps most importantly, he encouraged the Xhosa’s supernatural view of the world, that spirits were active in the everyday world. Case shows that Taylor’s missionary project, contra most anthropological analyses, actually culturally empowered global peoples.

This is a stark counter-narrative to the usual story of Western missionary imperialism. Case argues for empathy and a more complex narrative. He writes, “It was extremely difficult for most nineteenth-century Americans to speak about civilization without assuming that whites were in some way smarter, more productive, and more moral than other races around the world.” Given this context, American evangelical missionaries seemed quite enlightened indeed, especially compared to their liberal mainline counterparts intent on spreading “civilization.” According to Case, Taylor and other evangelical missionaries “began to downplay Western conceptions of race, ethnicity, gender, and nationality.”

In Part II of my overview of An Unpredictable Gospel, I’ll explain how William Taylor’s experience in Africa not only exhibited indigenous empowerment—but also sparked a “global reflex” that challenged Gilded Age Methodism in the United States.