I’ve written a good deal about the centuries following the fall of the Roman Empire in the West, the era that in parts of Europe we commonly call a Dark Age. This was a remarkable time for Christian survival and growth in some areas – and of the destruction of the faith in others. This was for instance the great age of Celtic saints Patrick and Illtud. Another very important member of the group is all but forgotten today, or at least given nothing like the credit he deserves. In fact, he may be two of the greatest saints you never heard of. This is a complex story, and an interesting example of how really important figures slip out of official history.

In modern Wales, St. Ninian was a very famous figure because he indirectly gives his name to Ninian Park, the longtime stadium of Cardiff football team. (The park is actually named after Ninian Crichton-Stuart, a local aristocrat killed in the First World War). But according to mainstream church history, Ninian was in his day a very important figure.

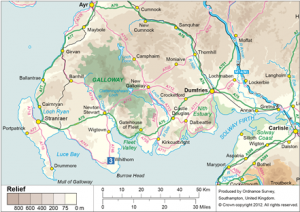

According to Bede, writing about 730, Ninias (Ninia) converted the Picts of Southern Scotland, and created a great church at White House, Candida Casa, which became Whithorn. Because the church was dedicated to the Gallic Saint Martin of Tours, who died in 397, early writers assumed that Ninias was operating at this time, perhaps into the early fifth century. Those dates are not impossible, but they are much earlier than most comparable British saints, and scholars have long favored later dates for Ninias – at least in the early or mid-sixth century.

Ninias/Ninian was the subject of an eight century Miracula Nynie Episcopi, Miracles of Bishop Ninia. He also became the focus of later biographies, which suggest that their writers really had not much more information about him, although they do cite some intriguing names. They knew that he was important, but not exactly why. Churches dedicated to Ninian can be found all over southern and central Scotland. Rioght through Reformation times, Whithorn was a major center of pilgrimage.

Ever since the mid-nineteenth century, scholars have wondered exactly who this Ninian was, or indeed, his exact name. Bede calls him Ninias, and only in the twelfth century does the form Ninian appear. It’s a long story, but let me summarize briefly. A consensus today suggests that both those names might conceal an original version, which began not with N but with U, two letters easily and frequently confused by medieval scribes. And while the name Ninia or Ninias is not known before Bede’s time, the form Uinniau certainly is, and it belongs to some well-known and influential men.

In later Irish, the name appears as Finnian, and one saint of this name is almost certainly the same individual as the Ninias recorded in Scotland. This is Finnian of Moville, in Newtownards, County Down, Northern Ireland. Finnian would have been active around 540 AD, and he seems to have been a distinguished scholar and teacher, who produced some very significant pupils.

The greatest of these (around 540) was St. Colmcille, founder of Iona, and one of the most venerated Irish saints. Moville was one of Ulster’s most important monasteries and schools.

Of course, the identification with Ninias does not just depend on a similarity of name. Once we compare the lives of the two men, we see some impressive coincidences in terms of their career, and the individuals with whom they interacted. Some scholars even think that the name of “White House” could have been taken from a form of Finnian’s name, meaning “Fair.”

It’s not too difficult to see what has happened here. In the post-Roman era, roughly that horrible century and a half after 450, Uinniau was a missionary and scholar who set up monastic settlements on both sides of the Irish Sea, in Northern Ireland and Southern Scotland. The distance between the two regions is tiny, and we know the sea routes were very well traveled. (Bold modern souls have even swum this so-called North Channel, which is about twenty miles wide).

The British remembered part of his career, the Irish the other, but not until modern times was this heroic figure rediscovered, or perhaps reintegrated.

We see his influence in the Penitentials, a vast and important literary genre in the early Irish church. These books provided detailed guidance for confessors hearing sins, and allotting penances and punishments, and in the process, they give massive information about social, cultural and sexual history. Although these survive chiefly in Ireland, the oldest of all penitentials were clearly composed in Britain and under the guidance of British churchmen. One was the famous Gildas, author of one of the very few contemporary documents to survive from Britain in this era. Somewhere between 520 and 540, Gildas was consulted in these penitential matters by an Irish cleric called Vennianus, who is very probably our Finnian of Moville – and who is also our Ninias.

To avoid even more confusion, I am not here getting into another contemporary Saint Finnian, associated with Clonard, and a near-contemporary of our man of Moville. The exact relationship between these two may also need to be redefined. One “Finnian” wrote the very earliest Irish Pentiential.

Here’s a suggestion: Uinniau/Finnian/Ninias lived some sixty years or so after St. Patrick. If a couple more of his writings had happened to survive, perhaps the medieval and later worlds would have regarded him as one of the very greatest Western saints, on a par with Patrick. He was one of the founders of that great British-Irish Christian tradition.