Visual art can be a terrific source for the history of religion, and that is especially true when we look at Christian missions through the centuries. Those visuals don’t just reflect our idea of a topic, they do much to shape it. For many people today, the word “missionary” is faintly ludicrous, and conjures up thoughts of sturdy Victorians in pith helmets, serving the cause of colonial exploitation. To see what I mean, just go to Google images and feed in a phrase like “missionary Africa cartoon.” It’s not a friendly picture.

Once, of course, matters were very different. Missionaries were heroic figures, the leading edge of Christian civilization, and they were depicted accordingly in paintings by major artists, in prints and (yes) cartoons.

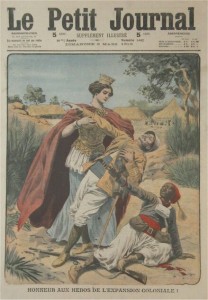

Certainly, the resulting images abounded in stereotypes that we find difficult to take today.

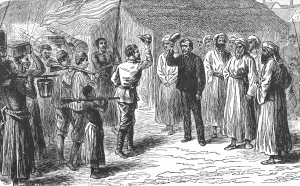

The native recipients of the gospel are portrayed as almost childlike, except when they are martyring a European missionary, when they become actively diabolical. The images are, to say the least, paternalistic.

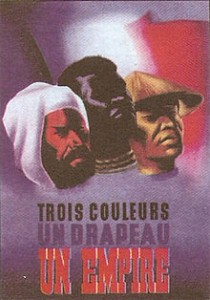

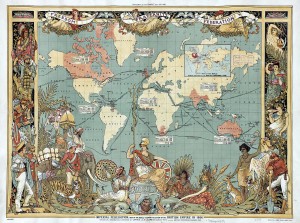

Nor can we easily see such pictures without thinking of the larger imperial ambitions in progress at the time.

But if we want to see how ordinary Christians in Europe or North America conceived their role, and the expansion of the church, these visuals are an extraordinarily rich resource.

They tell us about the changing ideology of mission. They also indicate the heroic role-models that young Western Christians aspired to imitate – even to the point of a heroic death.

This is a classic example: Victoria presents a Bible in The Secret of England’s Greatness by Thomas Jones Barker (1863). The title says it all.

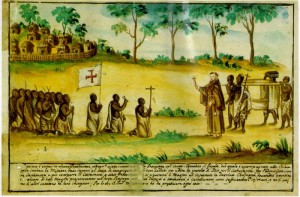

I won’t reproduce them all here, but there is an excellent collection of eighteenth century images of missions and missionary work in the Kongo.

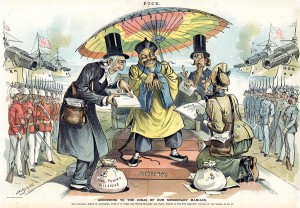

Meanwhile, for a completely different (and hostile) take on the missionary enterprise, here is an 1895 cartoon.

The text reads: “According to the ideas of our missionary maniacs: The Chinaman must be converted, even if it takes the whole military and naval forces of the two greatest nations of the world to do it.”

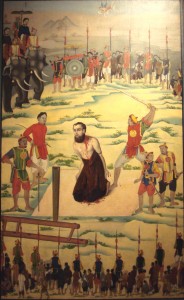

Some of the richest images stem from the golden age of Catholic mission between c.1550 and 1720. The reason for this is simple, in that this was also a magnificent age of European painting, and some of the greatest artists of the day tackled missionary themes. I’ll look at some examples in my next post.