Easter is a time for sober reflection on matters of death and Resurrection, and not, one would think, an occasion for humor. Throughout history, though, some Christians at least – including major cultural figures – have so relished the news of Christ’s triumph that they cannot contain their glee in declaring the good news. Without apology, then, I turn to one of the greatest medieval explorations of the Easter experience.

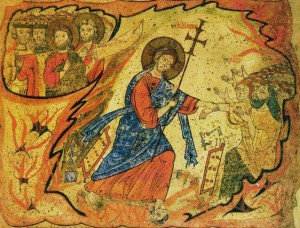

I am referring to William Langland’s epic poem Piers Plowman, written around 1380. A sprawling vision of contemporary England, with a radical social and religious critique, Piers Plowman is a worthy rival to Chaucer’s work in the English literary canon. Langland describes the aftermath of the crucifixion from the standpoint of the Lords of Hell. He uses ancient apocryphal works like the Descensus Christi ad Inferos, the source of the Harrowing of Hell story, but he reinterprets it through the eyes of a major poet, and dramatist. It works very well as a play, and even, amazingly, offers important female roles.

I am referring to William Langland’s epic poem Piers Plowman, written around 1380. A sprawling vision of contemporary England, with a radical social and religious critique, Piers Plowman is a worthy rival to Chaucer’s work in the English literary canon. Langland describes the aftermath of the crucifixion from the standpoint of the Lords of Hell. He uses ancient apocryphal works like the Descensus Christi ad Inferos, the source of the Harrowing of Hell story, but he reinterprets it through the eyes of a major poet, and dramatist. It works very well as a play, and even, amazingly, offers important female roles.

The setting is after the Crucifixion, but before the Resurrection, that Holy Saturday when Christ descended to Hell, to liberate the righteous dead. We first hear the dialogue of the women Truth and Mercy, a really funny duo – the prissy and domineering Truth, and the kindly Mercy. Truth reports the dreadful situation of the old patriarchs and prophets lying in Hell. And as everyone knows, there is no escape from there. Mercy tries to interrupt, only to be harshly answered by Truth.

Never believe that yonder light will raise them up,

Nor have them out of Hell – hold your tongue, Mercy!

You are speaking nonsense. I, Truth, know the truth.

That once something is in Hell, it never comes out.

Actually, that’s a modern paraphrase. Just out of curiosity, here’s the original Middle English:

Leve thow nevere that yon light hem alofte brynge,

Ne have hem out of helle–hold thi tonge, Mercy!

It is but trufle that thow tellest–I, Truthe, woot the sothe.

For that is ones in helle, out cometh it nevere;

But Mercy will not be silenced: “Through experience, she said, I hope they will be saved.” And in the Christian world view, Mercy will always win.

And just then, a distant voice cries “Attolite portas.” – Lift up your gates!

The Lords of Hell become increasingly alarmed. Satan dreads what is to come, because he has already lost to Christ once, in the struggle over Lazarus. Lucifer takes comfort, though, in knowing that they were only fulfilling the contract with God. After all, God had decreed that sin should lead to Hell, and human beings had violated his commandment in the Garden of Eden. So could God or Christ really resort to treachery or trickery? Surely not, says Satan – but even so, I worry.

The sense of menace among Hell’s leaders builds, as does our anticipation, culminating in Christ’s approach to the doors of Hell:

Again the light bade unlock and Lucifer answered,

“Who is this? What lord art thou?”

The light soon said, “The King of Glory

The lord of might and of main, and all manner of virtues

The Lord of virtues.

Dukes of this dim place, open these gates right now

That Christ may come in, the son of Heaven’s king.”

And with that breath Hell broke, despite Belial’s bars,

In spite of any thing the guards could do, the gates opened wide.

Patriarchs and prophets, People dwelling in darkness,

Sang Saint John’s song, “Behold the Lamb of God!”

Jesus then justifies his “raid,” which did indeed defy rigorous legality. Jesus, though, will not accept Satan’s rule. He explains the theory of original sin, but also why he does not propose to be bound by it. You, Satan, led humanity into your power by deceit and trickery, and that fact voids any legal claim you can propose. You robbed God of his proper possession, and God will now return the favor:

Although reason records, and right of myself,

That if they ate the apple all should die,

I promised them not here Hell for ever.

For the deed that they did, thy deceit it made;

With guile you got them, against all reason,

For in my palace, paradise, in the person of an adder,

Falsely thou fetchest there the thing I loved.

Thus like a lizard with a lady’s face

Like a thief you robbed me; the Old Law grants

that tricksters be tricked – and that is good reason.

Dentem pro dente et oculum pro oculo.

[A tooth for a tooth, and an eye for an eye].

Therefore a soul shall quit a soul, and sin drive out sin

And all that man has done wrong, I, man, will amend it.

This message was all the more powerful for a medieval world structured according to precisely defined rights and obligations, set down either in documents or customary form. Any party that breached the contract or treaty must suffer the consequences without complaint.

To borrow Langland’s character, those were the harshly clear words of Truth. Christ, though, preaches and practices the law of Mercy, which towers above all other values. Langland’s Christ is admirably unconcerned with the letter of law – even divine law. And after Christ’s victory, Mercy and the other women celebrate with a dance.

Langland creates a superb drama, but it is also powerful theology. Piers Plowman teaches us some unforgettable lessons, about the fundamental ignorance of the Devil and his forces, and their slavish obedience to what they perceive to be iron laws, passed down by their warped vision of God. Christ, though, rises above simple, stupid legalism.

Modern historians point out that Langland’s critiques often echo those of the proto-Protestant Lollard movement that was subverting church authority in the England of his time. If he was not himself a revolutionary, he was playing with deeply critical ideas.

But here’s the core message: in the Christian world-view, never try to silence Mercy.

Hmm, Love Wins. That might make a good book title.