In my undergraduate years, I studied early and medieval Celtic history, with a heavy concentration on matters Irish. A couple of lessons from those days help understand contemporary academic debates, not to mention our appreciation of Christian history.

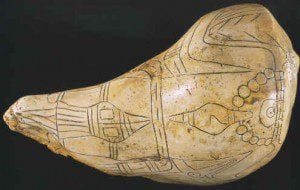

The first issue arises from an excellent recent issue of American Archaeology, about the important Native American site of Spiro Mounds, Oklahoma, which operated from the ninth century through the fifteenth. Elizabeth Lunday has an article with this subheading: “For years Spiro Mounds was thought to be a Mississippian chiefdom that flourished from trade. But a noted Spiro expert now believes it was a ceremonial center. The first excavation of this important site in more than forty years could confirm or refute his hypothesis.” So was it an economic center, or ceremonial? In support of the latter view, archaeologists note the burial of key ceremonial figures. The “Spirit Lodge” was associated with “channeling the power of the sacred goods and revered dead of the community.”

My problem is that we absolutely should not segregate such concepts as “ceremonial” or ritual from “economic.” Just suppose that one of those Spiro chiefs or priests was miraculously transported to contemporary Europe, say to Ireland in 900. He would have felt totally and utterly at home in one of the country’s monasteries, such as Clonmacnoise or Glendalough or Armagh. Each place was formed as a ritual/ceremonial center to commemorate a specially venerated saint. Over time, pilgrims came from all over the island to that place, bringing gifts, which accumulated to spectacular proportions.

The cult of particular saints, like Patrick or Kevin, thus supported a huge amount of economic activity, and the work of craftsmen and merchants. Everything contributed to “channeling the power of the sacred goods and revered dead of the community.”

The key events of the year, though, were the feast days of the famous local saints, and Patrick’s day was only one of a great many commemorated around the island. On that day, the monastery in question became a thriving commercial center for trade, meeting, socialization and gift exchange, not to mention artistic and musical celebration. You could become a serial pilgrim, spending the year hitting a succession of such fairs, much as modern day Hindus circulate around the multiple shrines and feasts of Mother India.

Although that kind of activity occurred all around medieval Europe, Ireland was special because, before the Vikings, it had no towns or commercial centers except for what clustered around the monasteries. Irish trade and urbanization was wholly synonymous with what the monasteries and saints offered.

So were these activities ceremonial/ritual or economic? Emphatically, yes and yes, and I would strongly assume that Spiro played a very similar role indeed, given the lack of “secular” towns or cities in the Americas north of Mexico. Flourished from trade or flourished from being a ceremonial center? That really strikes me as an utterly false division.

The bottom line: looking for the “secular” in pre-modern times is a hopeless quest.

And that brings me to my second takeaway, namely about the Vikings and their impact on medieval Europe. The Vikings hit monasteries brutally hard, and in Ireland especially, they targeted their attacks brilliantly to coincide with the fast days of the great saints, when the monasteries were teeming with lay visitors. They usually carried off many slaves, especially women. We know a lot about this activity because other monks reported it in agonizing detail.

Modern scholars have learned a great deal about the Vikings and their complex social life. They rightly stress that the Norsemen were not simple thugs, that they gave a vast stimulus to economic life, their art was impressive, and so on. These themes all emerged strongly in the recent British Museum exhibition on “The Vikings: Life and Legend.” That exhibit stirred a great deal of commentary in the press and on the Internet.

All of which is fine, but here’s the problem. In an attempt to revise the Vikings’ images as mindless savages, we often hear these days an argument that goes something like this. The Vikings were traders, they were immigrants, their effects on European society were beneficial. The reason we think so ill of them is that they targeted churches and monasteries, making the clergy hate them, and those bigoted priests and monks wrote their polemical histories accordingly. Anyway, those monks were greedy exploiters, so sacking the monasteries was probably a good thing.

I quote Neil Oliver, author of a recent book called Vikings, who scorns the monks’ denunciations of the Norsemen:

In truth, the unpardonable sin of the Vikings was to be pagan, still committed to the gods Odin and Thor. The peoples of Scandinavia were the last in Europe to accept Christianity and for as long as they remained heathen their violence against Christians was unclean and unforgivable. So the grief of Alcuin and the rest of the hand-wringing clerics was nothing more than the holier-than-thou pronouncements religious bigots are wont to make about those they consider unbelievers. Ruthless and violent the newcomers certainly were, but they only gave as good as they got.

Charitably put, this is baloney, as we see from earlier remarks about the role of monasteries and churches in societies. No, church writers did not attack the Vikings because they were pagan. Nor did Vikings pass by the nearby big secular cities so they could go and kill monks. They hit the monasteries because they were the centers of population, of trade and of economic activity, and where you were likely to find the local country people gathered together. Where secular centers did exist, as in Paris, the Vikings happily sacked them too. They raided churches because that’s where the treasures of the community were.

One of Oliver’s arguments is that in Ireland or Britain, for instance, Christian lords themselves often engaged in horrendous massacres, desecrating churches and monasteries and slaughtering their occupants. Hence, why were the Vikings singled out for doing exactly the same thing, if not for their inconvenient paganism? But here’s the problem. If you look at the excellent Irish records, you do indeed find some such Christian-led massacres and desecrations, but virtually all of them occurred after the Viking onslaught. That is, the monasteries and churches were largely respected before that date, but the Vikings just fundamentally changed the rules of the game – they really were utterly different from what had gone before. That’s not a new finding, and there’s no excuse for not acknowledging it.

If you feel like presenting a favorable side of massacre, rape, robbery, and mass enslavement, go ahead. I’m sure the Islamic State is always looking for effective Public Relations people. But don’t think the Vikings gained their reputation just by being anticlerical, or being pagan. They really were as savage as their reputations suggested. And they hit the monasteries because those stood at the essential heart of Christian society.

And just incidentally, no, the Scandinavians were not the last people in Europe to accept Christianity. That would be the Lithuanians in the fifteenth century.