There are not very many contemporary accounts of Mormonism in which the author is expelled from the Hill Cumorah Pageant. Avi Steinberg was not passing out illicit evangelical tracts to audience members, nor was he smoking pot behind the LDS Visitors Center. Instead, he was rehearsing for the show under an assumed name. “Like a sinner,” Steinberg confides, “I felt somewhat relieved to be caught.”

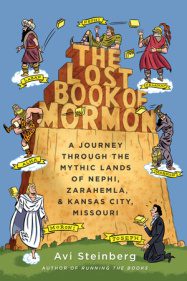

Steinberg’s The Lost Book of Mormon is a romp through the Book of Mormon’s certain and uncertain setting, from Jerusalem to Central America to western New York to (almost) the Garden of Eden. It’s a book about an underappreciated scripture, but perhaps even more about the uncertainty facing all aspiring writers and also about young people who find themselves an ill fit for their religious environs. Along the way, Steinberg’s self-reflective self-doubt sometimes threatens to overshadow his story (but turns out to be a critical part of that story). And his summaries of Mormon history sometimes feature more wit than accuracy. In 1834, Joseph Smith marched to Missouri from Ohio in an attempt to recover the Saints’ Jackson County properties, not to “explore sites for future settlement in the Missouri Territory.” Smith did not leave behind quite so many as “at least forty-eight grieving widows,” though one could allow that whether the figure was thirty-three or forty-eight is not the most germane question. His tone will rankle faithful Latter-day Saint readers, as when he terms Emma Smith the prophet’s “number-one wife” or Joseph Smith a “small-time neighborhood sorcerer.” In the end, though, The Lost Book of Mormon is funny, winsome, and thoughtful.

Steinberg’s The Lost Book of Mormon is a romp through the Book of Mormon’s certain and uncertain setting, from Jerusalem to Central America to western New York to (almost) the Garden of Eden. It’s a book about an underappreciated scripture, but perhaps even more about the uncertainty facing all aspiring writers and also about young people who find themselves an ill fit for their religious environs. Along the way, Steinberg’s self-reflective self-doubt sometimes threatens to overshadow his story (but turns out to be a critical part of that story). And his summaries of Mormon history sometimes feature more wit than accuracy. In 1834, Joseph Smith marched to Missouri from Ohio in an attempt to recover the Saints’ Jackson County properties, not to “explore sites for future settlement in the Missouri Territory.” Smith did not leave behind quite so many as “at least forty-eight grieving widows,” though one could allow that whether the figure was thirty-three or forty-eight is not the most germane question. His tone will rankle faithful Latter-day Saint readers, as when he terms Emma Smith the prophet’s “number-one wife” or Joseph Smith a “small-time neighborhood sorcerer.” In the end, though, The Lost Book of Mormon is funny, winsome, and thoughtful.

Steinberg begins his story in Jerusalem, which Lehi’s family flees prior to its destruction at the hands of the Babylonians. As he quite correctly notes, the Book of Mormon, as a “sequel” should, opens with a bloody bang. He then joins a Book of Mormon archaeology tour in Guatemala, led by a tour guide who identifies possible Nephite and Lamanite sites. Finally, there’s the Hill Cumorah Pageant debacle and a denouement in Missouri.

In Joseph Smith, Steinberg sees another would-be writer trying to find his place in the world. Or, in Joseph’s case, doing a bit more than that. In a comment that demonstrates his sympathy for Smith, Steinberg understands Joseph’s angst at losing the first 116 pages of his Book of Mormon translation. “Even with the direct intervention of heaven-sent angels,” he writes, “with the aid of powerful magic and clairvoyance, producing a book turns out to be an unbelievable pain in the [rear]. This seems very true to life.” So it is! When visiting Palestine, Mark Twain lamented that the biblical land of Israel was much smaller than he envisioned. Its heroic kings were minor tribal leaders; the great battles were, as Steinberg paraphrases, “shepherds’ squabbles.” The literary critic Edmund Wilson once climbed the Hill Cumorah and reached the same conclusion about Joseph Smith. But as Steinberg points out, the stories of the Bible were audacious and bold. “In the end they staked their entire identity on their stories,” he writes. “So it was with Joseph, landless and broke, standing on a small hill imagining Nephi escaping from ancient Jerusalem late one night through the city wall, book in hand.”

As Laurie Maffly-Kipp once pointed out in “Tracking the Sincere Believer,” we as Americans are so forgiving of self-invented men like Benjamin Franklin and Dale Carnegie. We admire their process of self-creation, but we (and I am talking about non-Mormons who ultimately do not accept Smith’s claims) cannot be so forgiving of Joseph Smith.

Steinberg describes himself as recovering Orthodox Jew (I had never connected Orthodox tzitzits and the tallit katan to Latter-day Saint temple garments). He’s gentle on his Mormon companions throughout The Lost Book of Mormon. There’s no condescension toward their beliefs. Steinberg understands that religion can imprison and oppress, but he also realizes how fun this stuff can be. “The main thing,” the guide for the Central America Book of Mormon tour encourages his group, “is to have some fun with it.” The Hill Cumorah Pageant, for example, includes missionary strategies, long rehearsals, and service projects. But it’s also summer camp for Mormon families. I looked up the application page, which doesn’t seem to restrict participation to Latter-day Saints, and wondered if I could persuade my family to join me for two weeks of living in a Palmyra college dorm. Probably not.

I found the Hill Cumorah section the best part of the book. Latter-day Saints have convinced pretty much no outsiders that the Book of Mormon is a historical account of ancient peoples. Except one part of the story is true. Joseph Smith published a hefty work of scripture in 1830, founded a church that accepted the Book of Mormon’s claims, and created the movement that makes its stories alive.

For Steinberg, the weight of his alias is too much. “I’d nearly gone out of my mind in four days as Yosef [his alias, Hebrew for Joseph],” he laments, “what would it be like to live an entire life as Joseph?” Steinberg finds that he is Joseph, a young man desperately seeking to find his place in the world and find his story to tell. His small subterfuge seems rather pardonable.