This is puzzling.

On multiple occasions, I have written about the ancient text known as 1 Enoch, which the early church regarded as almost canonical. From the early Middle Ages, though, the book was mostly lost to the West, and was only rediscovered in the eighteenth century in Ethiopian translations. Although this lengthy book deals with many subjects, one long section (chapters 72-87) is an astronomical and calendrical treatise, concerning the stars.

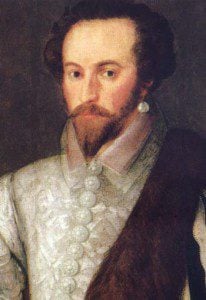

Now here’s the problem. In 1616, Sir Walter Raleigh (he of discovering tobacco fame) wrote his History of the World. This includes a scholarly and seemingly specific Enoch reference:

But of these prophecies of Enoch, Saint Jude testifieth; and some part of his books (which contained the course of the stars, their names and motions) were afterward found in Arabia Felix, in the Dominion of the Queene of Saba (saith Origen) of which Tertullian affirmeth that he had seen and read some whole pages.

Raleigh knows of a book attributed to Enoch, which includes astronomical material, and that fits 1 Enoch perfectly. Raleigh bases this comment on Origen, specifically his Homilies on Numbers.

All of which is well and good, and he is accurately summarizing the Origen passage – except for the note about the Arabian discovery. Nor is that cited in Tertullian, who regarded Enoch highly as a prophet, and wrote a good deal about him.

It is perfectly plausible that part of the astronomical section might have been discovered in antiquity, in Arabia or elsewhere, and that this was noted in some patristic (Byzantine?) source that Raleigh had read somewhere along the way. In this text, though, he was going on memory, because he was in prison at the time of writing, without full access to his normal library.

So what was Raleigh thinking of? I have never seen a convincing answer to this question. Could he really have been using a source otherwise unknown to scholarship?

What is doubly interesting here is that we know that different portions of what became 1 Enoch originally circulated independently, and the Astronomical Book was a free standing text. Several copies of it were found at Qumran. Raleigh’s note suggests the finding of a truly ancient version of the material, before it had been combined with the other portions. But what on earth is the source? Am I missing something obvious?

Any thoughts?

Problem now solved, I think!

The following is an update, December 2, 2014:

Based on the helpful and insightful comments below, I have been able to resolve the problem I identified. I stress that these commenters gave me the essential leads I needed for the solution.

My main source for this is Ariel Hessayon, “Og King of Bashan, Enoch and the Books of Enoch,” in Ariel Hessayon and Nicholas Keene, eds Scripture and Scholarship in Early Modern England (Ashgate Publishing, 2006), 1-40.

I summarize. In the fifteenth century, Rome had a sizable Ethiopian community, and Ethiopians traveled here. In 1548, an Ethiopic New Testament printed in Rome.

One member of the Ethiopian religious community here was a monk who in 1546 met the brilliant antiquary Guillaume Postel, and among other things, allegedly explicated the work of Enoch to him. In his book De Etruriae Regionis (Florence 1551), Postel expressed his belief “Enoch’s prophecies made before the Flood were preserved in the ecclesiastical records of the Queen of Sheba, and that to this day they were believed to be canonical scripture in Ethiopia.” He wrote more on this in his De Originibus (1553). So that’s the Queen of Sheba link.

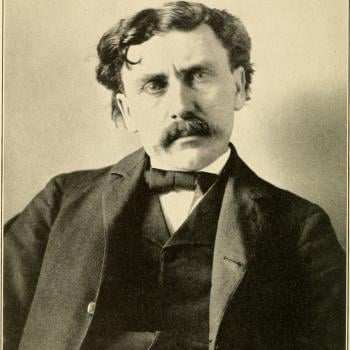

Postel’s work found an English readership through scholar John Bale (1495-1563). Magician John Dee also owned a copy of the De Originibus, which he annotated heavily. It’s not surprising then that around 1580, when John Dee and Edward Kelley channeled what they believed to be mystical symbols, they interpreted them as “Enochic.” Dee, seemingly, knew everybody, and certainly was friendly with Walter Raleigh. Among other things, Dee inspired and supported voyages of colonial exploration, and actually coined the name “British Empire.”

But the short answer as to where Raleigh got his “Queen of Sheba” reference was, probably: from Postel, via Dee. He misremembered the source he was using as Tertullian.

My compliments to Ariel Hessayon for fine scholarship.

Case closed?