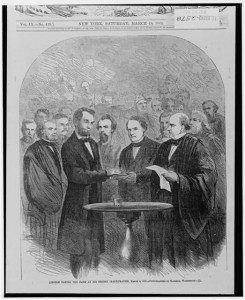

Yesterday was the 150th anniversary of Abraham Lincoln’s second inauguration as President of the United States. On that date, Lincoln delivered an address that, while never quite rivaling the Gettysburg Address in terms of fame, has nevertheless earned the lasting admiration of many Americans.

Carl Sandberg termed it ”the great American poem”; Frederick Douglass praised it as “more like a sermon than a state paper.” Douglass more closely hits the mark. Still, it seems wisest simply to praise the second inaugural as a theologically informed and politically shrewd speech.

The address drips with biblical quotation and allusion. Despite its brevity, Lincoln in his address quotes the old and new testaments repeatedly. Themes of sin, providence, and reconciliation dominate.

But Lincoln’s speech was no exercise in theological speculation, his straightforward explanation for the war’s bloody toll notwithstanding. Lincoln understood the war “the woe due to those by whom the offence came,” the offense being slavery. In other words, Lincoln contended that both northerners and southerners were guilty for slavery’s origin and persistence. The wages of sin were death. And if God willed that the war continued “until all the wealth piled by the bond-man’s two hundred and fifty years of unrequited toil shall be sunk, and until every drop of blood drawn with the lash, shall be paid by another drawn with the sword … ‘the judgments of the Lord, are true and righteous altogether.” Ultimately, God had chosen to punish the United States with the scourge of war.

If placing the war within the overarching frame of God’s providence, Lincoln did not hesitate to name and blame the war’s more proximate causes. And here Lincoln, despite professing a desire not to judge, judged harshly. For starters, Lincoln blamed the South for starting the war. He observed that as he delivered his first inaugural, “insurgents agents were in the city seeking to destroy it without war.” If both North and South “deprecated war … one of them would make war rather than let the nation survive; and the other would accept war rather than let it perish.” No moral equivalence here.

And on the matter of slavery, Lincoln returned to the position of his Republican Party in the late 1850s and during the 1860 presidential campaign. Everyone, Lincoln said, knew that slavery caused the war, as southern slaves “constituted a peculiar and powerful interest … To strengthen, perpetuate, and extend this interest was the object for which the insurgents would rend the Union, even by war; while the government claimed no right to do more than to restrict the territorial enlargement of it.” Lincoln here reminded southerners (and northern Democrats) that the North had not begun the war out of a desire to extirpate southern slavery.

Next comes Lincoln’s famous observation that both sides “read the same Bible, and pray to the same God.” He concludes that the “prayers of both could not be answered; that of neither has been answered fully.” In between, however, Lincoln inserts a wry aside: “It may seem strange that any men should dare to ask a just God’s assistance in wringing their bread from the sweat of other men’s faces; but let us judge not that we be not judged.” Lincoln here alludes to Genesis 3. Note, however, that while professing not to judge, Lincoln has done exactly that! Slavery was a terribly evil that the South started the war in order to defend and expand. Lincoln allowed that the Almighty had his own purposes, and in so doing guarded against northern self-righteousness, but he also resolutely affirmed the justice of the Republican and Union causes.

Finally, Lincoln’s famous closing sentence called on northerners to proceed “with malice toward none; with charity for all; [and] with firmness in the right, as God gives us to see the right.” They should win the war and then “care for him who shall have borne the battle, and for his widow, and his orphan” and then “do all which may achieve a just, and a lasting peace.” Here Lincoln extends a message of charity and reconciliation and also signals his distance from more radical Republicans who want a measure of vengeance against a defeated Confederacy and a more thorough reconstruction of southern society. The exact path Lincoln would have traveled after the war remains rather unclear. In his final days, he was contemplating limited black suffrage.

None of this is to take issue with the plaudits the Second Inaugural has rightly received. We would do well to remember, that Lincoln had always been less of a religious idealist and more of a careful and shrewd politician. Fortunately, those two aspects of his thought came together at the time of his second inauguration.