I have been exploring the history of Christianity within the Persian Empire, a subject very well known to specialists working on that area, but less so to their counterparts who study the story in its “mainstream” (Mediterranean and European) forms. Before writing about this in any more detail, it’s important to understand the geographical setting, which means locating some very famous names. Geography may or may not be destiny; but it is very important indeed for the fate of religions.

Anyone even slightly familiar with the ancient world, or with the Old Testament, knows certain names of peoples, regions and great cities – Medes, Persian and Parthians, Susa and Persepolis. Actually placing them in relation to each other is quite a different matter. It matters enormously, though, because each of those regions was differently situated in relation to other nations and cultures. Some, like the Persians, looked west and south, towards Babylonia and the world of the “Persian” Gulf. Others, like the Parthians, never lost touch with Central Asia. At different times, different parts of the broader Persian world dominated, and that shifting emphasis gave a different political and cultural coloring to the empire’s outlook.

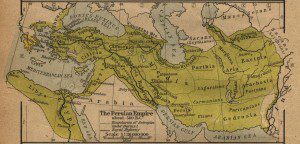

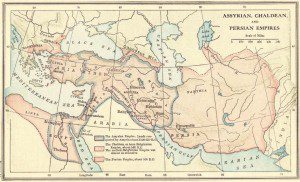

For convenience, I refer to this older map of the Achaemenid Empire, describing the world of c.500BC. (Click on it for more detail). I will just focus on the few regions that would be significant in Christian history.

Assyria and Babylonia together comprehend modern Iraq. Going eastward, we find the west and south-west of what we today call Iran. In Iran’s far south-west is the very ancient city of Susa, in Susiana (in the modern province of Khuzestan).

Just east of that, on the Persian Gulf, is the region of Persis (modern Fars), with its capital at Persepolis. This was the ceremonial capital of the Achaemenids, and Persis gave its name to the whole of “Persia.” Going north, into the heart of modern Iran, we see the land of the Medes, Media. When the Bible talks about the Medes and Persians, these are the peoples referred to. Parthia, meanwhile, lies to the far north-east.

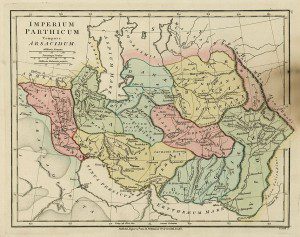

The Parthian (Arsacid) Empire flourished from 247 BC through 224 AD. It was then supplanted by the Sassanids, who prevailed from 224 through 651, when they were in turn conquered by the new force of Islam. The shift from the Parthians to the Sassanids also meant a move in the empire’s center of gravity, from the north-east to the southern region of Persis/Fars. The Parthians had ruled from different capitals, including Seleucia-Ctesiphon in modern Iraq, but the Sassanids definitively chose that as their royal seat.

Early accounts of Christianity in this part of the world are suspect precisely because it was so strong and flourishing in later centuries, and there were so many church writers who were striving to make claims for their city or kingdom. We can, though, dig behind these competing claims to trace the geography of expansion with some confidence.

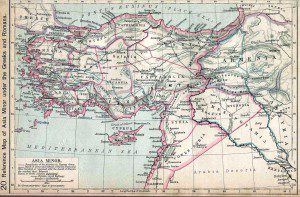

Christianity made its first impact in the distant western regions of what was then the Parthian Empire, in regions that today we place in northern Iraq or eastern Turkey. By the second century, the faith was well established in these borderlands between the two empires, in kingdoms like Osrhoene (with its capital at Edessa) and Adiabene (Arbela). It later gained a critical foothold in the Caucasus, in Armenia and Iberia. Sometimes Rome ruled all these lands, sometimes Persia prevailed, but most commonly, the empires shared the lands between them, while tolerating a network of buffer states.

As so often, Andrew Walls offers a concise summary that is both acute and provocative:

“The little buffer state of Osroene, on the Roman imperial frontier, was the early base of a remarkable Christian movement. In Edessa, its capital, are the remains of the oldest church building yet discovered, built at a time when no such thing was possible in the Roman Empire. Edessa, indeed, often does appear on maps of the early church. Unfortunately, it is usually at the eastern extremity of the map, yielding the idea that it represents the eastern extremity of a Christianity centered on the Mediterranean. If, however, we place Edessa at the western end of the map, and pigeonhole the Roman Empire for a while, we can observe a remarkable alternative Christian story. Early Christianity spread down the Euphrates valley until the majority of the population of northern Mesopotamia (i.e., modern Iraq) was Christian. It spread through the Arab buffer states …. It moved down to Yemen and was adopted by the royal house. It moved steadily into Iran proper, into the Zoroastrian heartland of Fars, and northward to the Caspian.” (I take this from Walls’s brilliant article, “Eusebius Tries Again,” International Bulletin of Missionary Research 24(2000); 105-11).

As I’ll show, the spread of Christianity into the Empire proper involved some real ironies. The harder the Persians fought against outside enemies, the more they found themselves, unwittingly and unwillingly, importing those alien ideas – including Christianity.