‘Tis the season for the road trip, not just for getting from point A to B, but for attending to history and geography along the way.

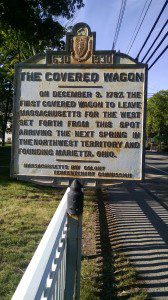

On the Old Bay Road going toward Ipswich, Massachusetts, now 1A North of Boston, a roadside marker identifies the site where the first covered wagon set off from Massachusetts to the West. The marker came courtesy of the Massachusetts Tercentenary Commission. In 1930, upon the 300th anniversary of the founding of the Bay Colony, and with leadership of renown Harvard historian Samuel Eliot Morison, the commission erected plaques to commemorate the deeds of Puritan settlers. Some tercentenary signs bear obvious relation to the site where they are posted: a meetinghouse stood here, an Indian attack occurred there. This one is not obvious. Why celebrate going West in so Eastern a place, a town with Atlantic-coast beach and clam-shack bona fides, a town founded by John Winthrop Jr., and renamed “Hamilton” in the 1790s in honor of the Federalist Treasury Secretary? Furthermore, what is the marker doing right in front of a New England church, white steeple and all?

The church has everything to do with those wagons going west. Setting those wagons forth was Manasseh Cutler (1742-1843), a Congregational minister educated at Yale, who served for decades at this church in Ipswich (turned Hamilton) Massachusetts. One of those do-all men in the generation of the American Revolution, he was a chaplain in the war, ran a school, supplemented his ministry with law and medicine, served in the Congress of the early United States, and made observations in astronomy and botany that earned him appointment to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. In the 1780s Cutler and his Ohio Company of Associates, veterans of the Revolution, negotiated with Congress for a tract of land in the Northwest Territory. Deciding how to organize that territory was one of the signal achievements of the Articles of Confederation government. The Ordinance of 1785 and the Northwest Ordinance (1787) established a process to bring territories to statehood in an orderly fashion, and to settle these midwestern lands with public education and without slavery.

Behold, the significance of the New England clergyman in the frontier history of America. In December 1787 the first of those Ohio Associates’ wagonloads assembled in front of Cutler’s church and set off. They made their way to the confluence of the Muskingum and Ohio rivers in April 1788, where they would found the town of Marietta, named after France’s Marie Antionette.

Layered into this laconic marker are some necessary reminders. To start, it points up the role of the east in shaping the west, these hardy pioneers not only lighting out for territories but being sent forth by a Yankee clergyman, carrying with them familiar institutions and communities, including ecclesial ones. Furthermore, it recalls the excitement vested in the region we now name the midwest. “Going West” in Cutler’s time meant going to places like Ohio. For the new nation about entering a new century, Ohio was about the most interesting state in the Union. It opened possibility for migrants to enjoy the fruits of their own labor, and was a laboratory of regional differences, with a northern portion established by settlers like Cutler’s folk, its region around Cincinnati dominated by settlers from the south. Some who drive through it these days might miss the significance of Ohio—though nineteenth-century French visitor Alexis de Tocqueville recognized it, admiring it as “one of the most magnificent valleys that has ever been made the abode of man,” a place where “a confused hum is heard which proclaims the presence of industry; the fields are covered with abundant harvests, the elegance of the dwelling announces the taste and activity of the laborer, and man appears to be in the enjoyment of that wealth and contentment which is the reward of labor.”

Just so, some who drive by the roadside marker in front of the Hamilton Congregational church might miss its magnitude. Driving across America presents many of these, claims to significance by places that might appear insignificant now, at least to casual passersby. But driving across America can drive home a key point of history 101 boilerplate, that America is not one lump but composed of states whose origin, settlement, chronology, and geography powerfully shape them and their relations to their neighbors.

Drivers, don’t fall asleep at the wheel.