What do you think of when you think of heaven?

Is your first thought God and Jesus, or is it your loved ones (spouse, parents, children, and pets)?

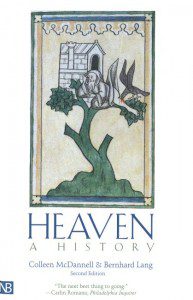

Over the past few years, I’ve dipped into Colleen McDannell and Bernhard Lang’s endlessly fascinating Heaven: A History, and I recently had the chance to read it straight through.

Over the past few years, I’ve dipped into Colleen McDannell and Bernhard Lang’s endlessly fascinating Heaven: A History, and I recently had the chance to read it straight through.

M&L (as I will abbreviate the authors hereafter) explain that two major views about heaven have dominated Christian thought about the hereafter: the theocentric expectation of seeing and praising the blessed Trinity and the anthropocentric longing to be reunited with family and friends. Many Christians have blended these two basic ideas, but at different points in Christian history the theocentric or anthropocentric model has predominated. Perhaps most intriguingly, M&L describe the decline of heaven in twentieth-century western Christian thought, a development common to both liberal and evangelical Protestants. (It occurs to me that if they were rewriting the book today, M&L might observe that contemporary Christians outside of Europe and the United States are probably far more open to vibrant and detailed images of heaven than their western counterparts). There’s far too much in this book for one post, so I’m going to discuss the history of heaven over several weeks.

That Christians would have a host of ideas about heaven is not surprising if one examines the varied beliefs about the afterlife present in both testaments of the Christian Bible.

If one begins with the Hebrew Bible, one finds several layers of traditions, beginning with Semitic ideas about the need for the living to placate their dead relatives who reside in the netherworld. As illustrated by Josiah’s reforms, some Israelites then rejected ancestor-related rituals in favor of worshiping the LORD alone. The dead were marginalized in Sheol. Perhaps influenced by Zoroastrianism, other Jewish writers anticipated the apocalyptic destruction and restoration of the earth followed by the bodily resurrection of the Jewish people. Hellenized Jews, by contrast, drew on Greek ideas about the ascent of righteous souls to the Elysian Fields or the Isles of the Blest, which they would enter through a gate. The spirit, but not the body, would survive. Philo of Alexandria (ca. 20 B.C. – A.D. 45) believed that certain, very righteous souls would ascend to higher realms. Enoch resided among the pure ideas, whereas only Moses had entered the very presence of God.

Not surprisingly given this background, debates about the afterlife play a major role in New Testament narratives and other writing. Perhaps most famously, a group of Sadducees — presumably upper-class Jews whom we know only through unsympathetic sources — ask Jesus about the afterlife implications of Levirite marriage:

Now there were seven brethren: and the first took a wife, and dying left no seed. And the second took her, and died, neither left he any seed: and the third likewise. And the seven had her, and left no seed: last of all the woman died also. In the resurrection therefore, when they shall rise, whose wife shall she be of them? for the seven had her to wife.

The synoptic gospels inform us that the Sadducees “say there is no resurrection”; their question is designed to show what foolishness the apocalyptic bodily resurrection would entail. Jesus responds that “when they shall rise from the dead, they neither marry, nor are given in marriage; but are as the angels which are in heaven.” As M&L summarize, “men and women would be angel-like, asexual beings.” As Jesus also called on his disciples to leave behind their families to follow him on earth, when they died, they would immediately be transported to the presence of God in heaven. There would be no marriage and no families. There would be no need to wait for a bodily resurrection. As M&L explain, Jesus was entirely “possessed by the idea of God,” and he expected his followers to be as well, both on earth and in heaven. Thus, early Christians formed “charismatic communities,” where the bonds of faith trumped familial and other social concerns.

Paul, by contrast, was somewhat more in tune with the Pharisaic expectation of a future resurrection. Unlike older Jewish apocalyptic ideas, however, Paul argued that the resurrected body would be “spiritual” rather than fleshly. When Jesus returned, living Christians would be changed “in a twinkling of an eye,” and dead Christians would be raised. Then, the redeemed community of saints will be in heaven in the presence of Christ and God. According to M&L, Paul did not expect the resurrection of the body, which would remain in the grave.

The Book of Revelation has greatly influenced the Christian understanding of heaven, from its opening vision of Jesus Christ to its closing vision of the city of God. In the fourth chapter of Revelation, John sees “four and twenty elders fall down before him that sat on the throne, and worship him that liveth for ever and ever, and cast their crowns before the throne.” This is an important moment. “Without losing its awe-inspiring celestial dignity,” M&L write, “heaven has become more human.” John also sees 144,000 resurrected martyrs from “all the tribes of the children of Israel,” then “a great multitude … of all nations, and kindreds, and people.” They are clothed in white robes and hold palms and praise God and the Lamb.

Here we find one of the most enduring Christian images of heaven: “Therefore are they before the throne of God, and serve him day and night in his temple: and he that sitteth on the throne shall dwell among them. They shall hunger no more, neither thirst any more; neither shall the sun light on them, nor any heat … God shall wipe away all tears from their eyes.”

Life in heaven, according to John of Patmos, will bear little resemblance to such earthly trials. The resurrected saints will spend eternity praising God and Jesus Christ.

Of course, the Book of Revelation does not end there. After a series of tribulations and battles, Christ and the resurrected martyrs will return to reign over the earth while Satan is bound. Then, the dead will be resurrected for a final judgment. At this point, it’s the lake of fire or eternal life on a renewed earth, with a massive new Jerusalem at its center, a giant temple dedicated to the praise of God. In John’s apocalypse, heaven is a staging ground for the saints’ eventual return to a renewed earth.

For M&L, a common thread in these various New Testament visions of heaven and the afterlife is their theocentric focus on eternity in the presence of God and Jesus Christ. They speculate that images of heaven that included more of a place for human relationships emerged once Christianity evolved beyond its early forms of “charismatic community.” Earthly life for Christians began to look very different, and so did their visions of eternity. That will be the subject of the next post in this series.