“God has given Christianity a masculine feel.”

I remember when John Piper said this at a pastor’s conference in Minneapolis, 31 January 2012. I wasn’t there. But I read the statement as quoted by the press; I read the elaboration on the Desiring God website; and I read the continued responses throughout social media.

And all I could think about was medieval sermons.

Now, I understand that everyone who has grown up with the Hollywood version of the medieval church, or who even has a basic understanding of the medieval ecclesiastical structure, is probably thinking, “What?!”

Yes, you are correct. Women could not be priests in the medieval church.

But this doesn’t mean that women were excluded from leadership roles (including preaching—I will talk about this in a future post), and it also does not mean that medieval Christianity had a masculine feel.

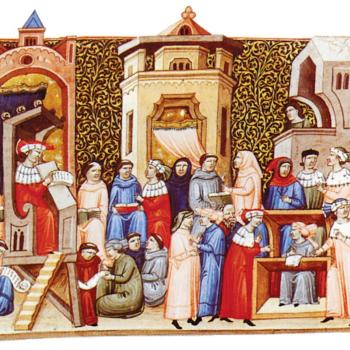

Let’s take a quick look at women in late medieval English sermons. Of course, the apostles preached their way through medieval sermons–performing miracles, interacting with Jesus, sharing the gospel, and laying the foundations for the beginning of what Ignatius of Antioch called the “Catholic Church” in an early second century letter.

But the male apostles were only part of the story. Late medieval English sermons highlight women as playing vital roles in the spread and practice of Christianity. When Thomas took the gospel to India, as related in the popular fifteenth-century sermon compendium Festial, it was a woman who was the first to recognize Thomas as a messenger from the true God. The sermon tells how a female minstrel, after witnessing a miracle performed by Thomas, cried out from the crowd, “Either you are God, or God’s disciple; for right as you said, it has happened.” Her words shamed the king and his courtiers to allow Thomas to preach, and ultimately Thomas converted both the king’s daughter and her husband to Christianity. When word reached Peter that Mary Magdalene—praised by medieval preachers as the first witness of Christ’s resurrection–was avidly preaching in France, he blessed her ministry. In fact, the title “apostle of the apostles” was so common for Mary Magdalene that the heretical followers of John Wycliff who challenged so much about medieval Catholicism accepted Mary Magdalene’s place as a “fellow to the apostles.”

Despite the patriarchal world in which they lived, late medieval English preachers rarely discussed wifely “submission” or the prohibition in Timothy against women teaching. New Testament references to women’s subordinate and silent status are almost completely absent in late medieval English sermons. (BTW—although this research is part of my current book project, some of it is already scattered throughout my publications.)

Instead, the controversy that concerned authors of Middle English sermons was the moment Mary Magdalene realized in John 20 that she was talking to the resurrected Christ. Jesus warned Mary Magdalene “noli me tangere,” or touch me not. Medieval sermon authors like John Mirk balked at this statement, “touch me not.” It did not seem to reflect the Jesus they knew—a Jesus whose actions highlighted a woman as the model for repentant souls (the woman with the alabaster jar to Protestants, the composite Mary Magdalene to medieval Christians); a Jesus who was continuously in the company of women like Martha of Bethany (the “hostess of God”); a Jesus, who according to medieval sermon stories, reached out and helped women along the path to salvation when their priests failed them; a Jesus whose birth by Mary righted the sin of Eve.

From theological explanations, to biblical exemplars, to even gender inclusive renderings of scripture and salutations, women fill the pages of Middle English sermons. When John Mirk tried in Festial to explain the Trinity in an understandable way, he used a woman in the place of Christ: “As this Adam was formed of earth [he is] the first person, and Eve of Adam [as] the second person, and a man [their first child] of them both that was the third person.” When the clerical compiler of a fifteenth-century sermon manuscript, Bodleian Library MS Greaves 54, quoted John 6:44 (“No man can come to me, except the Father which hath sent me, draw him”), he made sure that women knew they were included: writing instead, “no man nor woman come to me but my Father draw him.”

I do not share the beliefs of the medieval Catholic Church. Yet the significant role women play in late medieval English sermons makes me pause. I can’t help but wonder, after seeing women through the lens of medieval sermons, if perhaps the reason Christianity seems so masculine today is because our modern perspective makes it look that way.