As teachers prepare for the approaching fall semester, questions surrounding artificial intelligence in the classroom are ramping up once again. Should we seek to integrate AI into assessments and assignments? How should we monitor its use? And how should we treat cases when students use AI on papers? While I have encountered numerous opinions about AI, both positive and negative, I must admit I have never been a fan of this technology in academic spaces—but I think there might be some appropriate uses elsewhere. Still, something seemed problematic to me about the technology, even outside the possibility of cheating or assessment design.

Amidst my summer reading, I was encouraged to reflect on methods for reading Scripture with the Christian tradition, and surprisingly, this clarified my previous caution about AI. Artificial Intelligence widely undermines how Christians have talked about formation throughout the history of the church. In other words, AI has non-Christian assumptions, which challenge formative practices.

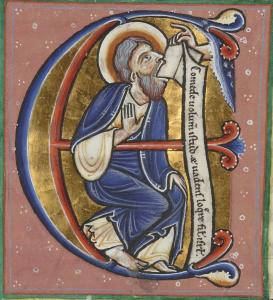

Lectio Divina

The book that sparked this reflection is Hans Boersma’s Pierced by Love: Divine Reading with the Christian Tradition. Therein, Boersma discusses the theological foundations and formational practices of reading Scripture throughout the medieval church. If you are unfamiliar, lectio divina, which Boersma calls ‘divine reading’, is an approach to Scripture that treats the word of God as just that—divine. A divine book requires divine reading. Origen, a theologian from the third century elaborates,

“Devote yourself first and foremost to reading the holy Scriptures; but devote yourself. For when we read holy things we need much attentiveness, lest we say or think something hasty about them. And when you are devoting yourself to reading the sacred texts with faith and an attitude pleasing to God, knock on its closed doors, and it will be opened to you… Do not stop at knocking and seeking, for the most necessary element is praying to understand the divine words” (Origen, Letter of Origen to Gregory 4).

Notice here that the key to understanding Scripture is not a comprehensive grasp of the historical context, nor a perfect understanding of the original biblical languages, but spiritual discipline. Of course, history and languages are very important (as Origen himself notes), but we must not forget this text is by God, and thus our reading requires conformity to God to understand it properly—it necessitates virtue. Further, we must note this is a process of devotion, attention, and prayer. It is not as if you can read one commentary and unlock all the Scriptures meaning—it takes time and effort.

Medieval Illustration for Lectio Divina: Eating

Boersma employs a number of medieval writers in his work, such as Hugh of St. Victor, Bonaventure, and Aelred of Rievaulx, but I want to focus on Guigo II and Anselm of Canterbury, especially their discussion of lectio divina as chewing and eating food (See Boersma, Pierced by Love, Chapter 5). Guigo II was a Carthusian monk from the 12th century who discussed lectio divina as a means to ascend to God in his Ladder of Monks. He writes, “Reading, as it were, puts food whole into the mouth, meditation chews it and breaks it up, prayer extracts its flavor, contemplation is the sweetness itself which gladdens and refreshes.” (Guigo II, Ladder of Monks 3) Central in this notion of scriptural interpretation as eating is the process, in which contemplation only occurs if one goes through stages—if we place food in our mouth (read), chews its meaning (mediate), and notice its flavor (pray). Only then can readers find true refreshment (contemplation).

Likewise, Anselm of Canterbury, the famous theologian and bishop, writing a century earlier uses the same language in Meditation on Human Redemption.

“Shake off your disinclination, constrain yourself, strive with your mind toward this end. Taste the goodness of your Redeemer, be aflame with love for your Savior, chew His words as a honey-comb, suck out their flavor, which is sweeter than honey,’ swallow their health-giving sweetness. Chew by thinking, suck by understanding, swallow by loving and rejoicing. Rejoice in chewing, be glad in sucking, delight in swallowing.” (Anselm, Meditation on Human Redemption, 230).

For the bishop, lectio divina begins by chewing (rational inquiry and thought), moves to sucking (understanding, or grasping the reality of the passage), and ends with swallowing (rejoice and awe at the meaning). We might be mistaken to think this is an easy process though, as if lectio divina is as simple as opening our pantry and snagging a few Oreos. Anselm paints a different picture, as he exhorts his readers to ‘shake of their disinclination’, to engage in the difficult process that is scriptural interpretation—to ‘strive’ with their mind. Prayer, meditation, even reading itself is a slow practice that requires mental and physical energy. Boersma summarizes Anselm, here: “lectio divina involves hard work. We must take our time chewing the text itself. What is more, we should be glad to engage in this laborious activity of thinking about what the text might mean” (Boersma, Pierced by Love, 100). Contemplation of God’s Word requires great effort.

Efficiency is not always our friend.

Returning to the use of AI, we should not only be asking how or what questions about its employment, but also the why questions. Why are we so attracted to this technology? I am sure there are a number of reasons out there, but two seem central: efficiency and comfort. It is far more efficient to have AI compose an email or a paper for me than to painstakingly write out word after word, or do the reading and research myself. It is more comfortable to ‘outsource’ all this work, so we can focus on the ‘important’ things, leisure or more pressing tasks. That is to say, AI is often developed and employed so we might skip the ordinary processes of life; the processes themselves hold us back.

But latent in this view is an assumption that these tasks do not have any pedagogical value, as if we are not formed by the process of our activities. Of course, this is not just an issue of AI—many of our modern technologies have this same aim, of pushing efficiency for the sake of our supposed comfort. But, if we take something like lectio divina seriously, we realize the process itself is absolutely central—and it takes years! Would it be ‘easier’ to simply receive God’s revelation without any spiritual work? Of course! But that is not how the tradition has viewed scriptural interpretation. There is no IV that can deliver the refreshment of contemplation, which skips over chewing, sucking, and swallowing—it comes through the process of eating. As Boersma argues: “lectio divina is an exercise in patience. It resists the temptation of jumping straight into contemplation… lectio divina is a slow and often painful process that takes seriously the sacramental character of God’s revelation” (Boersma, Pierced by Love, 16).

I am not saying that lectio divina and writing emails are the same, nor am I saying that AI has no valuable applications. But we must first ask ourselves, amidst the debates over AI: does the task we are seeking to avoid with AI have any pedagogical value? Should we skip this process? Surely not all processes lead to positive formation, but Christians (at the very least) must admit that God created us to be formed by our habits and tasks—we are embodied and create in time, after all. We grow, change, and hopefully flourish, through the lifelong process of sanctification. Perhaps we might reconsider our use of technologies, when we note how processes can form us. To grow, we must engage in the patient work of ordinary practices that shape us into better thinkers, people, and Christ followers. With the Christian tradition, we might be wary of skipping the process, as AI often tempts us to do.