Very recently, on June 16, Christianity Today published the article Gender and the Trinity: From Proxy to Civil War. Author Caleb Lindgren writes that the current debate over th e nature of the Trinity is especially significant because it involves like-minded theologians dividing over a core Christian belief: the nature of the Trinity. Is Jesus, the second person of the Trinity, eternally subordinate to God the Father, and–if so–does that divide the Triune God into three separate persons? Lindgren writes, “the opposing sides are calling into question each other’s commitment to historic Christianity. Accusations of ‘constructing a new deity’ and ‘reinventing the doctrine of God,’ are flying fast and thick, along with calls to ‘exclude such people from holding office in the church of God.’ Likewise, protests that such accusations ‘do not represent our view fairly’ and ‘suggest that Scripture itself is outside the bounds of orthodox Christianity’ in turn call into question the critics’ commitment to gospel-centered theology.”

e nature of the Trinity is especially significant because it involves like-minded theologians dividing over a core Christian belief: the nature of the Trinity. Is Jesus, the second person of the Trinity, eternally subordinate to God the Father, and–if so–does that divide the Triune God into three separate persons? Lindgren writes, “the opposing sides are calling into question each other’s commitment to historic Christianity. Accusations of ‘constructing a new deity’ and ‘reinventing the doctrine of God,’ are flying fast and thick, along with calls to ‘exclude such people from holding office in the church of God.’ Likewise, protests that such accusations ‘do not represent our view fairly’ and ‘suggest that Scripture itself is outside the bounds of orthodox Christianity’ in turn call into question the critics’ commitment to gospel-centered theology.”

Whoa.

I confess, part of me wants to remain an outside observer of this debate. I find it historically fascinating. Scholars can read the evidence and piece together what we think happened with the Christological controversies of the early church, but that is all. This fiery modern debate provides a tempting glimpse of what it possibly would have been like during the tumultuous 4th century. Didn’t Ambrose of Milan declare those “treacherous” who argued that Jesus was less than the Father while the Nicene Council condemned and “anathematized” them? Perhaps “anathematizing” is a bit more extreme then the name-calling and demands for resignation, but the underlying sentiment seems similar.

Of course, I shouldn’t minimize the enormity of this debate. Seriously. It is about the Trinity. It is about the nature of Christ. It also has manifested a significant aspect: that the subordination of wives to their husbands is reflected in the eternal subordination of Jesus to God the Father. Yes, this is a serious matter.

But how much of this modern debate is really new?

Teachings about the subordinate status of Christ persisted–sometimes even flourishing–from the 4th through the 9th centuries. Yes, the Council of Nicaea in 325 “anathematized” those who rejected the co-eternity of Jesus and the teaching that Jesus was the same substance as the Father (what we usually think of as Arianism). But, as Lewis Ayres so well demonstrates in his Nicaea and Its Legacy: An Approach to Fourth Century Trinitarian Theology (2004), the road to broad acceptance of Nicene Christianity was still difficult.

Jesus as subordinate to God the Father, in other words, is an old, often retold, story in Christian history (read the Ayres book). Although, I should stress, that this view always has been deemed heretical (at least until now….).

Nicene Christianity did eventually triumph in the early medieval world. John Mirk’s fourteenth-century Instructions for Parish Priests includes the Trinity within beliefs necessary for the Christian faith: belief on “the Father and Son and Holy Ghost,” belief that “the Father is God all mighty” and that Jesus Christ “is God’s son right, and both one God and of one might.” The text then employs the “water, snow, and ice” example to show that “the three, all water be. Thus the Father and the Son and the Holy Ghost be one God of might most; For though they be persons three, in one Godhead knit they be.” The insistence that both Father and Son are “one God” of “one might” and “the three, all water be” underscores Nicene teachings that Jesus and God are the same substance: Light from Light (or in this case, water from water).

Thus belief in the subordinate status of Jesus may not be a new idea; but it is an idea that mostly had disappeared by the 9th century.

Comparing the Trinity with marriage isn’t new either. Medieval Christians would have found this quite familiar. As the Feast of the Trinity sermon in John Mirk’s popular late medieval sermon series Festial states, “As Adam was formed of earth one person, and Eve of Adam the second person, and a man from them both the third person…Wherefore men should bear in mind of the Trinity, Holy Church ordains that in the marriage of a man and woman that the Trinity mass be sung.” Again, in the marriage sermon, Festial states, “you shall know that this order [the sacrament of marriage] was not first found by earthly man, but by the Holy Trinity of Heaven; Father and Son and Holy Ghost.”

Mirk’s reason for this marriage analogy, however, was not to explain a hierarchy within the Trinity. It was to help sanctify marriage. Isabel Davis writes in her 2011 article in Speculu m: A Journal of Medieval History, it is “not surprising to see the august force of Trinitarian doctrine brought in to dignify earthly marriage. Such justifications spoke, after all, to Mirk’s audience, confirming that the decision to marry was sanctioned and supported by Christian doctrine.”

m: A Journal of Medieval History, it is “not surprising to see the august force of Trinitarian doctrine brought in to dignify earthly marriage. Such justifications spoke, after all, to Mirk’s audience, confirming that the decision to marry was sanctioned and supported by Christian doctrine.”

(Indeed, with or without the Trinity, it is actually quite interesting how little late medieval English sermons discuss hierarchy within marriage….but that is a post for a later date…..)

Instead of using the Trinity to bolster marriage practice as Festial did, some medieval texts did use the marriage analogy to discuss the Trinity itself. Mystics like Julian of Norwich, writes Davis, used the Trinitarian comparison of God the Father and Jesus with Adam and Eve to emphasize the parental nature of God. “I saw and understood that the high might of the Trinity is our Father, and the deep wisdom of the Trinity is our mother, and the great love of the Trinity is our lord, and all this have we in kind and in our substantial making,” wrote Julian. Despite comparing the first two persons of the Trinity with the first married couple, Julian never casts the Trinity figures as husband and wife, nor does she (as Mirk does) suggest that the Holy Spirit is like a “child”. Mirk, with his insistence that Eve is like the second person of the Trinity (and it should be noted that Mirk is an outlier in this), perhaps comes close to Grudem’s claims for the “eternal functional subordination” of Jesus. But even Mirk’s ultimate picture is not one of hierarchy nor subordination; like Julian of Norwich, it is one of family. Belief in the Trinity, “there be three persons and one God in Trinity,” according to Mirk, brings one into the “genealogy” of Christ to “be as cousin and dear darling to God there without end.”

Marriage was a useful analogy for the Trinity in late medieval English religious texts. But it was used to sanctify marriage and emphasize the family community of Christianity. It was not used to enforce the eternal subordination of Jesus nor to reinforce wifely submission.

On the one hand, the participants in this modern Trinitarian debate are correct: not much is new.

One the other hand, the one thing that is new is very striking: the connection between the subordination of wives and the subordination of Jesus. The medieval world used marriage as an analogy for the Trinity; yet despite describing Jesus with feminine and marital imagery, they still perceived Jesus as “God of God, Light of Light, very God of very God; begotten, not made, being of one substance with the Father, by whom all things were made.” They did not perceive Jesus as eternally subordinate to the Father.

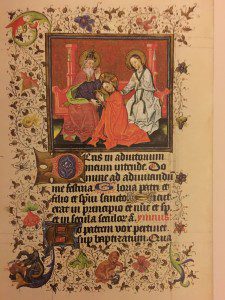

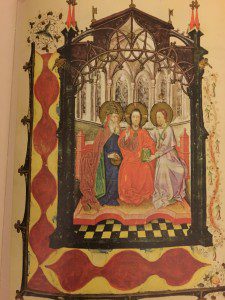

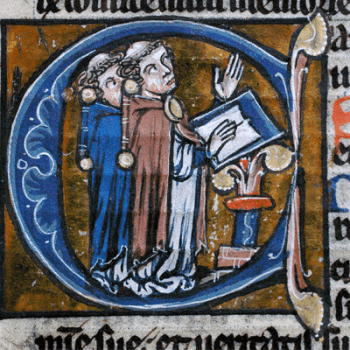

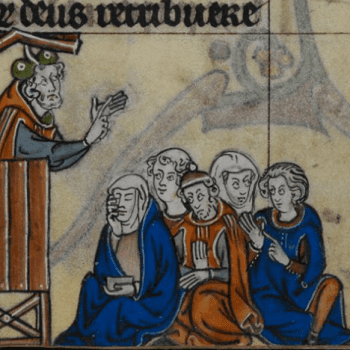

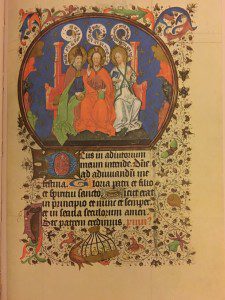

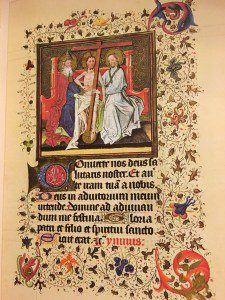

I would like to conclude with the four images included in this post. They are from a fifteenth-century book of hours made for Catherine of Cleeves. Note how the persons of the Trinity sit next to each other on a single throne, with Jesus in the middle. Only one image portrays Jesus in a subordinate posture to God the Father. It is the second image, and it portrays Christ taking the cup of humanity.

In these late medieval devotional images of the Trinity enthroned, it is only when Jesus is accepting his human commission that he kneels before God the Father. I think that sums up my point.