Today’s guest post comes from Blake Hartung, a PhD candidate in Historical Theology at Saint Louis University, where he is also an adjunct instructor. His interests are, broadly speaking, focused on early Christian history and literature, as well as the history of Christianity in the Middle East and Asia. Blake’s dissertation (to be defended in December 2016) examines the use of Scripture in the writings of Ephrem the Syrian. This fall, he will brave the job market in search of a career as a college or university professor.

Among the embattled Christian communities of Syria and the Levant, St. Ephrem the Syrian (ca. 307-373) is still heralded as their greatest teacher: “The Harp of the Holy Spirit.” Ephrem was a prolific writer of hymns, homilies, commentaries, and prose theological works. His writings were translated and emulated in every language of the early Christian world.

He was also a Syrian refugee.

Today, as the modern state of Syria endures a seemingly unending war and the greatest refugee crisis since World War II, it is a tragic irony that the most influential Syrian Church Father shared similar experiences of war and displacement. In the midst of his own appalling circumstances, Ephrem did not cease to teach and speak for the Christian community of his city. In fact, the great Syrian’s reflections on war—which he composed for public lament—offer a model for present-day Christians seeking to respond to the tragedies of our own time, most notably those in modern Syria.

Ephrem lived the great majority of his life on the Roman-Persian frontier, in the Roman border town of Nisibis (modern Nusaybin on the Turkish-Syrian border). During the Roman-Persian wars of the mid-fourth century, Nisibis was caught between the dueling ambitions of these two ancient superpowers. Ephrem and his community became the victims of no less than three sieges at the hands of the Persian army (in 338, 350, and 359). Ephrem’s words paint a vivid picture of the chaotic battle scene that unfolded during these sieges:

When the wall was breached, when the elephants pressed in,

When the arrows rained down, and when men acted boldly,

That was a sight for the heavenly beings! (Nis. 2.18)

The Persian siege of 350 was particularly dramatic and terrifying. The Persians diverted the water of the Migdonius River toward the walls of Nisibis in an attempt to weaponize the raw power of the river. This resulted in a channel of water surrounding the city, tantalizingly out of reach to the thirsty people of Nisibis, as Ephrem laments:

Who has seen a people burning with thirst,

With a wall of water surrounding them, but [who] were unable

To moisten their tongues? (Nis. 10.12)

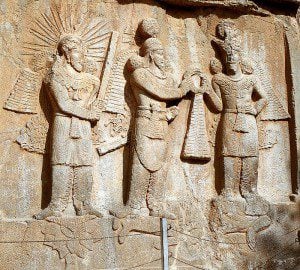

In 363, Emperor Julian “the Apostate” pursued a bold campaign aimed at crippling the Persians through a strike on the capital city of Seleucia-Ctesiphon, deep within Persian territory. Things did not go as planned. During a hasty retreat, Julian’s army was harried by Persian forces, and Julian himself was killed. In the chaotic aftermath, the new emperor Jovian signed a treaty with the Persians, which, among other things, surrendered Nisibis to the Persians. In one of his Hymns against Julian, Ephrem recounts seeing the corpse of the dead emperor brought through the streets, and the Persian banner raised triumphantly over Nisibis.

Likely suspected as a potential pro-Roman fifth column in the newly Persian city, Ephrem and the Christian community of Nisibis were forced to flee. Ephrem eventually settled in Edessa (modern Şanliurfa, Turkey), a city over 100 miles to the west. Upon his arrival in Edessa, Ephrem became a leading figure in the pro-Nicene church of that city. Ephrem has been remembered in Christian tradition as the “deacon of Edessa,” a characterization that is profoundly misleading. Ephrem was and remained a Nisibene, uprooted from his home by the devastation of war.

Ephrem did not reflect openly on the experience of forced exile in his extant writings. He did, however, compose several hymns lamenting the conditions faced by the city of Nisibis during the Persian sieges (preserved in the collection entitled Nisibene Hymns). Ephrem’s theological understanding of his experience of war was deeply shaped by Scripture. Like a biblical prophet, Ephrem saw the war through the lens of divine judgment, and thus as an opportunity to call his community to repentance. Inspired undoubtedly by the Psalms, some of Ephrem’s hymns take the form of laments, calling upon God to remember his people take and show mercy on them. For instance, in one hymn, Ephrem gives voice to a sense of abandonment on the part of the people of Nisibis:

How, my Master, can a desolate city,

Whose prince is far off, and whose enemy near,

Stand without [your] mercy? (Nis. 4.18)

In many of the hymns from the period of the Persian invasions, Ephrem speaks in the voice of the personified church of Nisibis. In the midst of siege, the church cries out for God to remember his covenant of marriage with her and save her from disgrace:

Do not give me over, lest it be thought that you have given me

a certificate of divorce, and driven me away!

My Lord, let them not call me forsaken and disgraced!

I have nothing that is worthy of mention before Your eyes,

For I am completely despicable. My God, remember for me

This alone: that I have set up for myself none other beside you! (Nis. 6.22-23)

When reading ancient writers like the Fathers of the Church, it is often exceedingly difficult to imagine these authors as real people who lived in particular times and places and had certain sets of life experiences. Ephrem’s reflections on the suffering and tragedy of war provide a helpful counterbalance to this tendency. They are tragically reflective of the unchanging reality of war. In addition, they offer a helpful model for reclaiming the biblical model of lament, exemplified in the books of Psalms and Lamentations.

Such a practice is all the more necessary in the modern media landscape, which bombards us with images of the Syrian Civil War and its desperate victims. With them, we should echo the words of their ancient compatriot Ephrem as he cried out for God’s mercy and peace:

I have lifted up my eyes to all [my] streets, and see how they are deserted!

Of a hundred, ten remained, and of ten thousand, a thousand.

Bring peace and fill up my streets with the clamor of my inhabitants! (Nis. 6.27)