Next week we’ll mark the 499th anniversary of Martin Luther posting his 95 Theses, taking us right up to the verge of a quincentenary that has already inspired a great deal of reflection on the historical and contemporary significance of the Protestant Reformation.

Tal’s the expert here, but not all Protestants make meaning of the Reformation in the same way. Dale Coulter, for example, wrote recently for First Thoughts about how Wesleyans understand its legacy.

So I thought I’d share how Protestants in my branch of that family tree tend to think about the legacy of Luther and the other reformers. I’d sum it up this way:

If we Protestants are “reformed and always reforming,” then commemorating the Reformation should cause us not so much to celebrate the past as to renew our mission and ministry in the present.

Michael Horton points out that “Reformed and always reforming” (Semper reformanda) actually originated not in the Reformation itself, but with a 1674 devotional. Its author, a Dutch pastor named Joducus van Lodenstein, was not just Protestant, but Reformed:

Some people today leave out the “Reformed” part or at least interpret it as “reformed” (little “r”): the church is “always being reformed according to the Word of God.” This means that to be Reformed is simply to be reformed and to be reformed is simply to be biblical. All who base their beliefs on the Bible are therefore “reformed,” regardless of whether their interpretations are consistent with the common confessions of the Reformed churches. However, this runs counter to the original intention of the phrase. Doubtless there are many beliefs and practices that Reformed believers share in common with non-Reformed believers committed to God’s Word. We must always remain open to correction from our brothers and sisters in other churches who have interpreted the Bible differently. Nevertheless, Reformed churches belong to a particular Christian tradition with its own definitions of its faith and practice. We believe that our confessions and catechisms faithfully represent the system of doctrine found in Holy Scripture. We believe that to be Reformed is not only to be biblical; to be biblical is to be Reformed.

But as a non-Reformed evangelical who thinks that his largely Lutheran theology is nonetheless reformed (and always in need of further reforming), I’m going to claim Semper Reformanda for the other Christian tradition that Horton attaches to Lodenstein: Pietism.

* * * * *

A year after Lodenstein published his devotional, a German Lutheran pastor named Philipp Jakob Spener wrote Pia Desideria, a booklet offering six proposals that could bring about “better times for the church” — and for a world still reeling from the terrible consequences of post-Reformation religious warfare. Both works were representative of Pietism, a new religious movement within Protestantism that spanned northern Europe and even reached European colonies in Greenland, North America, the Caribbean, and India.

For Pietists, the Protestant Reformation was both an inspiring and cautionary tale: a religious awakening that never fulfilled its early potential.

By the end of this week, Mark Pattie and I will have submitted to InterVarsity Press our own version of Pia Desideria. In a manuscript tentatively titled Hope for Better Times: Pietism and the Future of Christianity, we draw from the history of the Pietist ethos — not just as it took form in 17th and 18th century Germany, but in 19th century Sweden and 20th century America — to offer six Speneresque proposals for the continuing reformation of the church. If all goes according to plan, the book will come out just in time for the 500th anniversary of the theses posted by Luther — who is quoted or mentioned 14 times in our manuscript.

(Note: we particularly appeal to the history of our own denomination, the Evangelical Covenant Church, which describes itself as being “a Reformation church in that we see ourselves as standing in the mainstream of the Protestant Reformation,” but one that “continues to be shaped by Pietism….”)

To illustrate how Pietists try to live out the principle of “reformed and always reforming,” let me share some highlights from our reinterpretations of Spener’s first and second proposals — the two that most directly revisit the principles of the Protestant Reformation.

“The more at home the Word of God is among us, the more we shall bring about faith and its fruits”

We Covenanters affirm that Scripture “is the Word of God and the only perfect rule for faith, doctrine, and conduct.” So like Spener, and Luther before him, we’re sure that the most effective means for the reformation of the church is “a greater attentiveness” to God’s word. Spener wrote:

This much is certain, the diligent use of the Word of God, which consists not only of listening to sermons but also of reading, meditating, and discussion (Ps. 1:2), must be the chief means for reforming something… The Word of God remains the seed from which all that is good in us must grow. If we succeed in getting the people to seek eagerly and diligently in the book of life for their joy, their spiritual life will be wonderfully strengthened and they will become altogether different people.

But over time, the excitement of even “unlearned” Christians directly encountering the written word of God gave way to emphasis on competing Protestant interpretations of Scripture, as demarcated by confessions, catechisms, and other doctrinal texts that were more likely to produce “dead orthodoxy” than the “living, creative, active powerful” faith described by the early Luther.

“In sharp contrast,” Mark writes in our manuscript,

Pietists understood the Bible to be ‘an altar where we meet the living God.’ Far from simply being a receptacle for information — even God-inspired information — the Pietists held that the Scriptures are primarily a God-inspired gift for transformation. They taught that when we reverently approach the Bible, inviting the Holy Spirit to open our minds and hearts and lives to the Word of God, the Scriptures are the powerful means by which God can equip us to live out the good we were created to accomplish. They have the power to transform us by the renewal of our minds, as the Apostle Paul urges, so that we will not be conformed to this world, but rather able to discern and, by God’s grace, do the will of God (Rom 12:2).

The evocative description of the Bible as “an altar where we meet the living God” comes from a 1963 Covenant document called “Biblical Authority and Christian Freedom,” which responded to challenges by a fundamentalist pastor to the academic freedom of the faculty at North Park Seminary. The authors observed that

Christian vitality has not always been maintained by the majority. It has, in fact, often been found only in small minorities. Such minorities have no voice where conformity to “official” interpretations is required. Unless we wish to stifle all emergent spiritual vitality, we must be sure that people within our fellowship will be free to express themselves in ways which are different from the majority position without the fear of being labeled as disloyal.

“The establishment and diligent exercise of the spiritual priesthood…”

Or what Pietism scholar Jonathan Strom prefers to call Luther’s belief in the common priesthood, a view of the church that recognizes the diversity of roles and gifts within the Body of Christ — but also the shared duties that span the divide between clergy and laity. For Spener, all Christians (male and female, he added) were to “sacrifice themselves with all that they are,” pray for and bless others, and “let the Word of God dwell richly in them.”

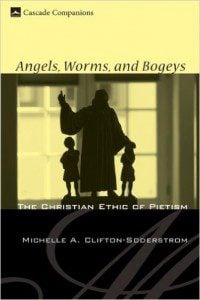

Here too, however, Protestants after Luther had fallen back into a traditional pattern that was both hierarchical and enervating. By the late 17th century, laments Michelle Clifton-Soderstrom, “the practice of faith was so limited to the clergy that not only did this bifurcate the common priesthood, it also became nearly impossible for the church to experience what Luther and Spener referred to as an enlivened faith” (Angels, Worms, and Bogeys, p. 66).

Here too, however, Protestants after Luther had fallen back into a traditional pattern that was both hierarchical and enervating. By the late 17th century, laments Michelle Clifton-Soderstrom, “the practice of faith was so limited to the clergy that not only did this bifurcate the common priesthood, it also became nearly impossible for the church to experience what Luther and Spener referred to as an enlivened faith” (Angels, Worms, and Bogeys, p. 66).

In our own time, I argue in the manuscript, recovering the common priesthood could help us respond to a different problem — namely, that

American Christians like me tend to conform ourselves to the values of our economy, rather than living out the counter-cultural values of the kingdom of God…. It means that we’re liable to have megachurch pastors who act like CEOs of Fortune 500 corporations and church planters who act like tech-sector entrepreneurs. It turns laypeople from full participants in the mission of the Church into fickle consumers and idle spectators.

Moreover (and here’s why I prefer “common” to “spiritual”), the priestly experience of coming into God’s presence also compels us to go out into the material messiness of the world — in short, the common priesthood must seek the common good. We must strive for what Donald Bloesch called “a holiness in the world, a piety that is to be lived out in the midst of the suffering and dereliction of men.”

So seeking the common good is itself a prod for the reformed to keep reforming, since we must constantly reexamine if we are meeting the fast-changing needs of a world being reshaped by economic, demographic, technological, political, and other forces. The time-fixed preferences of those within the church must always give way to the more urgently aching needs beyond our doors.

All of this means that Protestants shaped by the Pietist ethos can never — on this side of Christ’s return — regard reformation as a finished project. That, and our awareness of the limits of human understanding and effort, could make us hesitant to continue the work. But as Mark writes near the end of our manuscript,

when he announced his Great Commission, Jesus didn’t wait until all of his disciples’ doubts and questions had been resolved. He didn’t wait until their theology was in order. He didn’t wait until they wouldn’t make mistakes, embarrass him or one another, or let him or each other down. He just said, “Go!” and “I am with you!” and sent them out to participate in the gracious work of God in the world.

* * * * *

Horton argues that Semper Reformanda, rightly understood, “keeps us from making tradition infallible but equally from imbibing the radical Protestant obsession with starting from scratch in every generation. When God’s Word is the source of our life, our ultimate loyalty is not to the past as such or to the present and the future, but to ‘that Word above all earthly pow’rs,’ to borrow from Luther’s famous hymn.” And he suggests that “always being reformed” is more accurate than “always reforming,” since it is God doing this work — not a gathering of humans convinced of their own power, or so enraptured with present-day fads that they instinctively recoil from the foolishness of the past.

So I don’t mean to sound more progressive than I am.

But I do hope to sound as radical as I think Protestants should be.

Christians who believe in the authority of Scripture alone should never think too highly of any particular tradition. Christians who believe in salvation by the unmerited gift of God alone should never elevate anything humans have done within history to the level of the eternal and immutable. And Christians convinced that our religion is “reformed and always reforming” must always be open to God “making all things new.”