Many of you just finished the one month a year when “stewardship” is the focus of your church. You may have heard a sermon on “the stewardship of our resources” and (if you’re like me) chastised yourself for the unbidden, uncharitable thought that the preacher was actually making a passive-aggressive complaint about the state of the budget.

Now, having served for many years on our church‘s leadership team, I know that it’s important — spiritually and fiscally — to ask our members to renew their commitment to bear the costs of our mission and ministry. But I’m also glad that our pastor prefers the language of “whole life stewardship,” encompassing the right use not just of the financial gifts we’ve been given, but of our time and our talents.

And even of natural resources, like water. Even conservative Christians leery of the language of “environmentalism” (or even “creation care”) can nonetheless nod along with Southern Baptist leader Al Mohler: “We know that we will be judged for our stewardship of the earth.”

But as a historian, I wish that we would be more conscious of the truth that Creation encompasses not just space, but time. I wish that we would strive to be better stewards of the past.

* * * * *

I first started playing around with this idea last year, when I was invited to speak at the 125th anniversary dinner for a church in Duluth, Minnesota. “I suppose,” I mused, that “God could have created space without time, but he didn’t. Right off the bat, we get one day succeeding another and then another. ‘Make a joyful noise, all the earth’ (Ps 100:1), says the psalmist, to the God whose faithfulness spans ‘all the generations’ (v 5). Truly, God is both everywhere and everywhen. And nothing can separate us from his love: not time (‘nor things present, nor things to come’), not space (‘nor height, nor depth’), nor ‘anything else in all creation…’ (Rom 8:38-39).”

And it struck me that one distinctive of a quasquicentennial is that it’s the first such celebration when there’s no chance that someone present at the church’s creation was still living. (Save for the Holy Spirit, the church’s former pastor corrected me the next day in his sermon.) So I reappropriated Joshua’s valedictory description of the Promised Land and encouraged my audience to think of their church’s history as a “land on which you had not labored” and as “towns that you had not built.”

Those 125 years — or, at least, the memory of them — were a part of God’s Creation that had been entrusted to their care: not as owners, but stewards.

So what does that mean? Most obviously, it underscores the importance of preserving that past against the erosion that comes with the passage of time. So I celebrated that this church had not only kept an archive but digitized some of its holdings for a state-wide project. But I also argued that “what we can preserve of the past does not belong to any individual or group. (Again, it is not owned — it is entrusted.) So it ought to be interpreted in such a way that it is inviting to those new to it” — not framed as an exclusive heritage whose shibboleths remind “newcomers” of their marginal status in the community.

Finally, because it is not really our past, but God’s, I suggested that stewarding it ought to form us as a thankful people. “If we preserve the past,” I continued, “we preserve enormous potential for gratitude. If we interpret the past correctly, we invite new friends to join in our grateful response to God’s grace.”

* * * * *

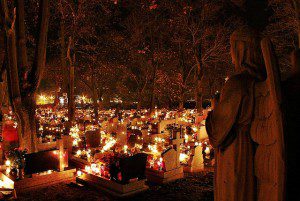

So why am I revisiting this talk, and the still-underdeveloped ideas it started to articulate, today? Because November 1st, for most Christians in the West, is All Saints’ Day.

The theology behind this festival varies from tradition to tradition, but at least in my church, All Saints’ is about remembering those who have passed on from this life to the next. (Which means that we’re probably conflating All Saints’ with All Souls’, but well, we’re Protestants. We also wait till Sunday to celebrate it.) It’s a temporal milestone that we’ve erected: a prompt to set to the side the distracting urgencies of the present and to think about lives that have passed into the past. It enacts stewardship, as a congregation collectively recommits to the responsibility of remembering.

(If you haven’t read Deuteronomy in a while — well, we’re Christians — page through it today. You’ll be instructed a couple dozen times “remember” or “do not forget.”)

In the process of remembering, many have pointed out, we re-member a Body that is regularly broken. Which means that stewarding the past risks re-opening its wounds.

Which is why, on a bit of further reflection, I added one idea to the end of that 125th anniversary talk before I shared it at my personal blog:

For a church… a 125th anniversary is an occasion to celebrate — but also an occasion to mourn. It reminds us to remember those who have died since the last such gathering. It revives the hurt feelings and sundered relationships that afflict every faith community I’ve ever known or studied….

Stewardship of the past is a stewardship of feelings, not just facts. It is a stewardship of happiness and sorrow, of celebration and regret. In short, stewardship of the past is stewardship of joy, rightly understood.

Writing in Surprised by Joy just before he recalls losing his mother while he was still a child, [C.S.] Lewis defines Joy as being

sharply distinguished both from Happiness and Pleasure. Joy (in my sense) has indeed one characteristic, and one only, in common with them; the fact that anyone who has experienced it will want it again. Apart from that, and considered only in its quality, it might also equally well be called a particular kind of unhappiness or grief. But then it is a kind we want. I doubt whether anyone who has tasted it would ever, if both were in his power, exchange it for all the pleasures in the world. But then Joy is never in our power and Pleasure often is. (p. 18)

So on this All Saints’ Day — but not only then — I urge you to be a steward of the past, to remember that dimension of God’s good Creation, and to share in that complicated, joyful task with others.