Memory Loss, Identity, and Whether History Matters

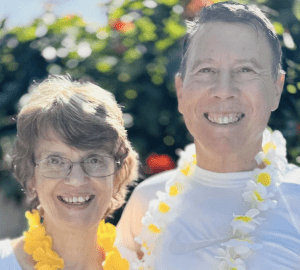

My mother was diagnosed with memory problems in her 60s, and doctors eventually labeled her challenges as Alzheimer’s Disease. Almost ten years into living with this disability, she is still socially engaged, travels to see family, enjoys entertaining her grandchildren, and enjoys caring for the pets she and my father fill their home with. While the lively and charismatic entrepreneur and professor that she once was has evolved into a sedentary and careful persona, she likes to look at us with her bright eyes and say that she’s “Still Alice,” referencing the novel by Lisa Genova. This phrase reminds us that even though she doesn’t remember much about what has happened already that day or even over the past week, she is still herself and we should take her seriously. This isn’t an essay about the challenges of caregiving or how to treat memory loss. Instead, it is a reflection on how memory impacts our identity.

Like so many of us when faced by a new difficulty—I started reading books about memory loss and end of life care. Dr. Genova’s own Remember: The Science of Memory and the Art of Forgetting was very helpful. Joanne Koenig Coste’s Learning to Speak Alzheimer’s and B. Smith and Dan Gasby’s Before I forget made some of the process personal and gave me ideas for what to expect and how to live in the moment with my mother. John Swinton’s masterful Dementia: Living in the Memories of God introduced me to the theology of dementia. I quickly realized that I had adopted many of our culture’s assumptions that our memories are who we are, and that if I lost my memories I would no longer be myself.

Instead, so many of those who write about their own experience or who study memory loss from an academic perspective warn us not to conflate memory loss with personhood and identity. As a Seventh-day Adventist, I have a life-long belief that we are embodied souls, and that our physicality is as much a part of who we are as the more transcendent and esoteric elements of our personhood/spirituality. Believing that my mother is fully herself and still my mother as long as she is here in her flesh became increasingly important to me. My mother is as much the child of God in this moment as she ever was—as a human in a body, she reflects the imago dei.

Of course, it is sad when she forgets who members of her family are, and it is distressing when she is confused. But often this is more about us and our own wishes than it is about her and her own identity. I have been reminded that memory loss can help us live here in the moment. My mother may not remember that I visited her or called her earlier in the day, but in the moment that we are together she is giving and receiving love.

Daniel Kahneman’s Thinking Fast and Slow many years ago alerted me to the fact that our “remembering self” can really betray our “experiencing self.” How we remember things, how they ended, becomes what happened. So even after a terrible war or an abusive relationship, we can say “well I’m glad that things turned out well in the end, so I guess we had to go through some hard times for that to happen.” This is normal and human, but it isn’t the only way to look at our history—and sometimes it can do violence to the experience of those (including ourselves!) who went through the experience.

I realized historians have a major role to play in this for the societies they live in and teach about. When we lean on a narrative arc that calls on us to remember certain things as vital to our collective identity, we may be snubbing or forgetting the actual lived experience of many people for whom that arc was a disaster. The memories that we prioritize and focus on become the identity. This is normal, but from time it behooves us to pause and think about those who don’t have memories or who lived through our history but aren’t remembered. They were just as much the children of God, just as important as those we are able to collectively mark tell stories about and who form a big part of our identity. Jordann Heckart’s recent reflection on women in the SBC shows how many young historians try to rectify this tendency.

Dementia, Alzheimer’s, senility, and even just mid-life memory loss have helped me develop some professional humility. I want memories. I ask my family and church to mark their lives and tell their stories and to help forge a family or church identity by remembering the past and encouraging each other through it. But even those who don’t have a long heritage within our family or church or community, or whose stories don’t make it into the official telling still were just as much part of what made us who we are. They are still full citizens of the community.

Remembering matters. I tell my mother stories about herself and things we did together—but mostly nowadays I’m doing that for myself. I show her pictures of her family and she often remembers who people are and some of what happened. But if someday she doesn’t, I won’t berate her with constantly trying to remember them. At least, that’s my plan. I have seen social media reels about memory loss with family members celebrating the moment their parent or family member finally remembered them for a moment after a long forgetting and how much that meant to them.

But I’m trying to ready myself for the fact that love (and pain) are borne in our bodies and the body remembers. In the moment I can give and receive love with my mother and I don’t need to torment myself or her with the attempt to get her to connect this moment with others who have gone before.

This is hard for me as a historian because I do think the past impacts the present and I want people to make those connections. And yet my ability to do this is limited. And none of my professional work as one of society’s “rememberers” can or should interfere with the vital work of loving people in their bodies in the moment. Making meaning of pain over time, trying to tie everything together to some sort of narrative arc that will give me a historical or personal “so what” can actually elide the equally important reality of the present.

And as a Christian who has often focused on belief and the importance of ideas and being able to tell a story or give witness for spiritual maturity, I’m learning to appreciate the spiritual depths of my mother and others whose memory loss means they won’t always operate within the church in the ways modern Christians have emphasized.

Memory loss, John Swinton argued recently in a conversation with historian Kate Bowler, does not elide our ultimate identity. “Memory is always very selective. And if it’s what you remember about your self that counts, then you’re in big trouble because you actually don’t remember what you think you remember. And so for me, the important thing is to take seriously what Paul says. You know, you find your identity in Christ. You don’t find identity in your neurology or in the things that you can or cannot do. You find your identity in Christ and your identity in Christ is hidden, as St. Paul says in Colossians. So you never really know who you are and so you’re not in a position to say, “That person is not the person they used to be” because you don’t know who you are yourself and you never will do until it’s revealed to you. So it’s always God’s memory that’s important.”

This historian is learning every day to love more in the present rather than relying on the past to form her sense of herself.