I posted last time about the importance of Freemasonry for understanding American history, American empire, and its religious dimensions. It is a lengthy story with large implications that stretch beyond Christianity. It also reminds us of a time in that history – only yesterday, in fact – when religion played a central role in politics.

Masons and Toleration

As a social and political movement, modern Freemasonry developed in the British Isles in the early eighteenth century. It was devoted to the idea of brotherhood, and admitted anyone who could subscribe to belief in one God, however that figure was imagined. Christians, Jews and Muslims all qualified under that criterion, as did any Hindus who could assert that the various gods of that faith were manifestations of a higher monotheism. Jews were welcome, and the fact that Jews were such enthusiastic Masons goes a long way to explaining their assimilation in both the US and the British Empire in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

And not just in North America. I remember the bafflement of that very fine historian Jonathan Steinberg, whose research showed that during the 1940s, the Italian military and large sections of the nation’s bureaucracy had engaged in a massive conspiracy to protect the country’s Jews from the Nazis. (I have posted about this at some length here). For the life of him, he could not work out why they had done so. Other than natural goodness, what possessed those Italian elites to act thus, and to act in such an organized and coordinated way? Then, at a late stage in his research, an informant pointed out what was obvious enough to Italians: all those generals, ministers and public servants, all those diplomats and spooks? “They were all Masons!” And with that clue, everything else fell into place. Yes indeed, there really had been a far-reaching Masonic conspiracy – a Deep State, if you like – and in this instance, it was working wholly for good.

Masons and Catholics

There was one gaping exception to that universal tolerance, namely Roman Catholic Christians. Indeed, much of European and American politics over the past two centuries has involved a running and often bitter confrontation between Masons and Catholics.

Initially, the hostility derived from Catholics themselves. Masons were happy to admit Catholics, but the Catholic Church in absolutist Europe was highly nervous about what they saw as a Protestant-derived deist cult that taught radical ideas of broad religious tolerance. Also arousing suspicion was the very strong ancient Roman and Roman Law dislike of secret societies of any and all kinds, on the basis that secret groups must have something wicked to conceal. That assumption was all the more likely when the group in question demanded that its members swear oaths of secrecy, framed in astonishingly bloody terms.

Various Popes sternly forbade Catholics from joining lodges. In the words of the pioneering 1738 document,

Now it has come to Our ears, and common gossip has made clear, that certain Societies, Companies, Assemblies, Meetings, Congregations or Conventicles called in the popular tongue Liberi Muratori or Francs Massons or by other names according to the various languages, are spreading far and wide and daily growing in strength; and men of any Religion or sect, satisfied with the appearance of natural probity, are joined together, according to their laws and the statutes laid down for them, by a strict and unbreakable bond which obliges them, both by an oath upon the Holy Bible and by a host [sic] of grievous punishment, to an inviolable silence about all that they do in secret together. But it is in the nature of crime to betray itself and to show itself by its attendant clamor. Thus these aforesaid Societies or Conventicles have caused in the minds of the faithful the greatest suspicion, and all prudent and upright men have passed the same judgment on them as being depraved and perverted. For if they were not doing evil they would not have so great a hatred of the light.

By 1917, a Catholic who joined a Masonic Lodge faced automatic excommunication.

Lest you think that I am putting all the blame on one side, Masons in various countries did become viscerally anti-Catholic and anti-clerical, and lodges became the foci of radical political movements aimed at undermining the established royal and Catholic ancien regime.

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Freemasonry became the principal vehicle for militant secularism and anti-clericalism. Those struggles almost led to overt civil war in France in the Dreyfus years, and they actually did spark armed violence in Spain and Mexico in the 1930s. It is scarcely an exaggeration to say that if you ignore Freemasonry, you have no hope of understanding Mexican history over the past century or so. Meanwhile, Masonic support of Jewish emancipation provoked reactionary denunciations of the “Masonic-Jewish” conspiracy, which was later expanded to include Bolsheviks. Masons occupied a primary place in Nazi and ultra-Right demonology.

American Struggles

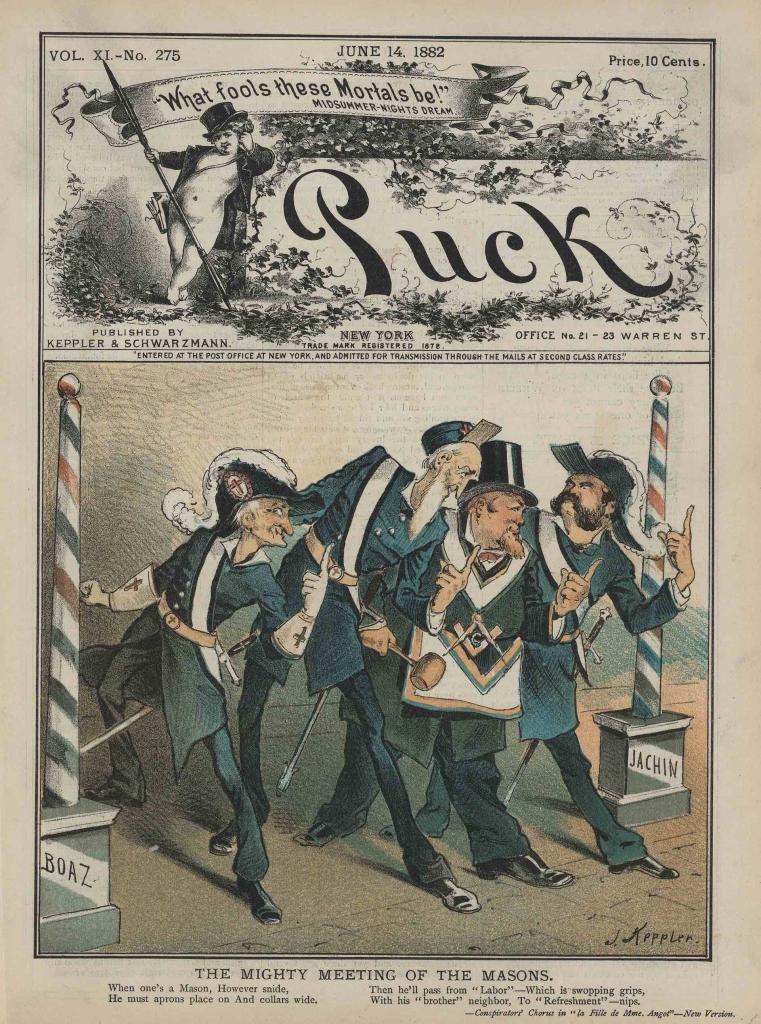

Matters were of course very different in the Anglo-American world, but Freemasons had a progressive bent. Through the nineteenth century, Freemasons and Catholics remained at odds over such issues as Catholic Emancipation, public education, and immigration. Masonic lodges tended to be anti-Catholic, and to be linked, explicitly or otherwise, to anti-Catholic mass movements.

This rivalry existed at all levels of society. Protestants enjoyed the great advantages of the Masonic order, in supplying mutual support in times of trouble, and also in creating invaluable networks in business, law and government. Feeling themselves excluded, the growing immigrant population (mainly Catholics) created their own pseudo-Masonic counterparts, most successfully the Knights of Columbus, which dates from 1882.

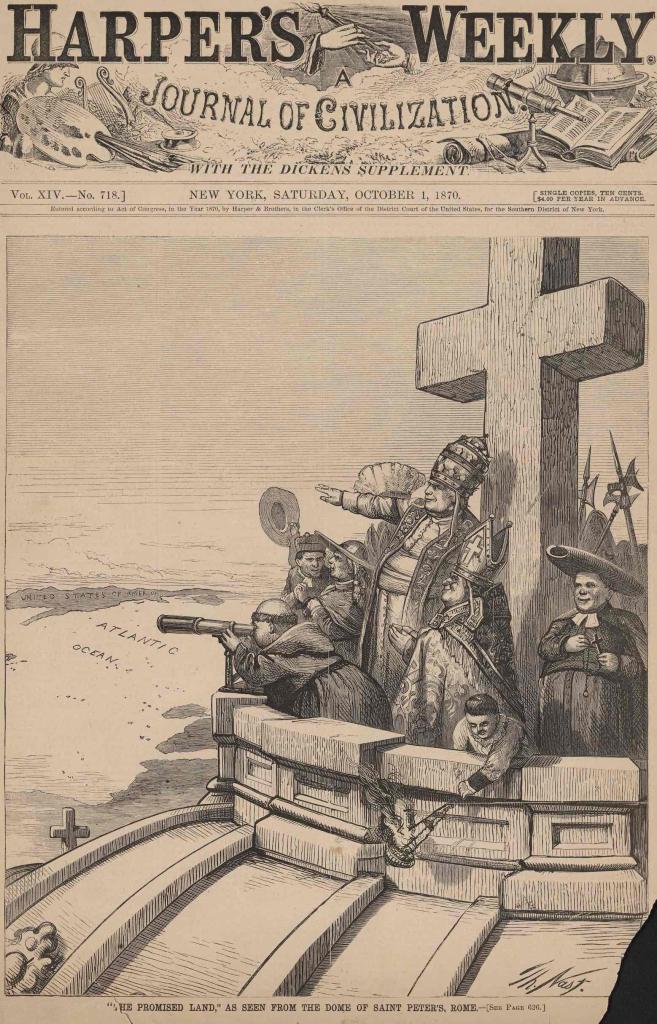

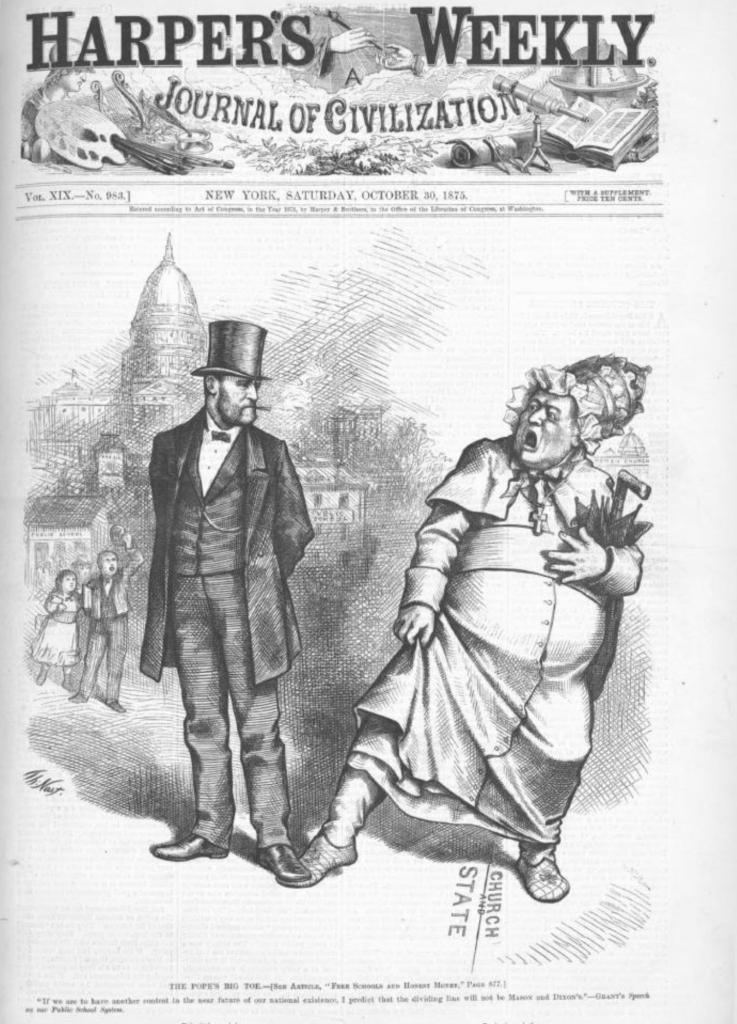

Outright violence was a real threat. In 1870 and 1871, more than sixty perished in Protestant-Catholic riots in New York City. Over the coming decade, some Protestants were thinking very seriously about the prospect of an actual civil war between the faiths. In 1875, President Grant spoke to a reunion of the Army of the Tennessee in Des Moines, Iowa, and although he never mentioned the word “Catholic,” nobody doubted who he was referring to:

If we are to have another contest in the near future of our national existence I predict that the dividing line will not be Mason & Dixon . . . but between patriotism and intelligence on the one side and superstition, ambition and ignorance on the other.

One potential detonator was the issue of public money being directed to Catholic institutions, notably schools. As Grant said, it was crucial to “encourage free schools and resolve that not one dollar of money appropriated to their support . . . shall be appropriated to the support of any sectarian school.” Republican Congressman James G Blaine actually proposed enshrining this principle in an amendment to the US Constitution. Although this failed, very narrowly, a majority of US states adopted Blaine Amendments in their own constitutions. When Blaine ran for President in 1884, one of his supporters famously labeled the Democrats as a toxic coalition of greedy liquor interests, the Roman Catholic church, and unreconstructed Confederates – that is, the party of “rum, Romanism, and Rebellion.”

Although not well remembered today, the great American popular movement of the late nineteenth century was the American Protective Association, which preached radical anti-Catholicism, and prepared to resist a feared Catholic coup d’état. Founded in 1887, the movement’s support ran into the hundreds of thousands at least, chiefly in the Midwest. Its founder was Henry F. Bowers, a Freemason, who structured the movement on Masonic lines, with regalia, oaths and initiations. The APA oath specified that,

I do most solemnly promise and swear that I will always, to the utmost of my ability, labor, plead and wage a continuous warfare against ignorance and fanaticism; that I will use my utmost power to strike the shackles and chains of blind obedience to the Roman Catholic church from the hampered and bound consciences of a priest-ridden and church-oppressed people; that I will never allow any one, a member of the Roman Catholic church, to become a member of this order, I knowing him to be such; that I will use my influence to promote the interest of all Protestants everywhere in the world that I may be; that I will not employ a Roman Catholic in any capacity if I can procure the services of a Protestant.

Masons and the Klan

These precedents shaped the post-1915 Ku Klux Klan, which became a national US phenomenon between 1921 and 1926, drawing perhaps five million members at its height. And at this stage, the KKK was at least as heavily devoted to anti-Catholic and anti-immigration causes as to anti-Black racism. The Klan found its local leadership in Masonic lodges, and especially among local Protestant clergy: “The Old Rugged Cross” was a main Klan anthem. In order to appeal to Masons and other fraternal organizations, the Klan offered a rich mythology and heraldry, with all the mystique implied by its hierarchy of “Hydras, Great Titans, Furies, Giants, Exalted Cyclops, Terrors,” its distinctive secret language, and an elaborate system of progressive initiations, of signs and countersigns. (I published on this at some length in my 1997 book Hoods and Shirts).

That background explains the very rapid growth of the Klan after 1915. However bizarre the new movement might seem to moderns, it spoke to an audience fully prepared to accept this world of secret signs and lodges, and much of the rhetoric was very familiar.

This political alignment created some outcomes that look distinctly odd today. If you look at Klan or Masonic literature in the 1920s and 1930s, you find a list of political concerns that look surprisingly, well, Left-wing. Masons favored strictly secular approaches to the public schools, as a bulwark against Catholic incursions, and they wanted a high wall of separation between church and state. They campaigned to spread Blaine Amendments throughout the nation. They fought hard against foreign interventionism. Catholics, on the other side, were pushing for armed US intervention against the anti-clerical Masonic regime in Mexico, and later against the anti-clerical Left in Spain. The Klan really had no problems with driving Catholics out of public life and public education, by force if necessary.

Racial Struggles and Culture Wars

So fundamental were these religious issues to American life that it is striking that they faded away so thoroughly. The last gasp of old animosities was probably the debate over JFK’s Catholicism in the 1960 Presidential election. Of course, anti-Catholicism morphed and evolved into other forms, but that is a different story. Meanwhile, Masonic numbers began their long withdrawing roar, to a present level of well under a million, and that in a country that is far more populous than it was in the 1950s.

I would offer three explanations for this change, each of which in its way supplied alternatives to religious rivalry. One was the Cold War focus on Communism, when Protestants and Catholics alike united in common cause, in which many of the key players and super-patriots were themselves Catholic. The other of course was the rise of racial politics during the age of Civil Rights, with a new emphasis on shared Whiteness. Finally, the rise of identity politics and culture wars from the early 1960s fundamentally redrew older political maps. The new political world was symbolized by Jerry Falwell’s Moral Majority of the 1970s, which sought to unite conservatives of all religious groups in a common movement.

So familiar have such developments become that we tend to forget an older America when Protestant-Catholic rivalries were so central.

On a different topic that should be of great interest, do check out this splendid upcoming virtual conference on Evangelicalism and Missions: Studies in the History of the Spread of the Gospel