I have written quite a bit on Freemasonry through the years, including several posts at this site. That material has a renewed significance for me given my present interests in empire, specifically American empire, with a special focus on its religious dimension. For the United States, as for the other empires of its time, Freemasonry played a critical role in the building and sustaining of empire. And by any reasonable standard, it was at its heart a religious movement, however much it overlapped with other churches and faiths. It had (and has) a distinctive theology, an elaborate body of mythology, and a complex ritual life. To be clear, plenty of recent writing has examined aspects of America’s Masonic history, but far less attention has been paid to its imperial role. (I list some major writing on the topic at the end of this post).

An oft told story describes the Battle of Minisink that occurred in upstate New York in 1779, during the Revolutionary War. A combined force of Loyalists and Mohawks defeated a Patriot militia unit, killing some forty men. The Patriot captain, John Wood, was on the verge of being killed when he gave a gesture that was believed to be a Masonic distress sign. As a faithful Mason himself, the Mohawk commander, Joseph Brant, immediately ordered that Wood’s life be spared, and the two men exchanged a Masonic handshake. As it turned out, Wood was not a Mason, and only by accident had he given what Brant took to be the appropriate gesture and handshake. Brant was furious, but regardless, he granted Wood’s life. On his release, the captain promptly joined the Masonic order. Some naïve people might even be surprised to find that the great Native American leader of the age was a Freemason.

The story points to the often surprising manifestations of Masonry on the frontiers, not to mention its strong military context. As I will show, both themes were commonplace – however odd this particular story might appear. If we want to understand many aspects of American history, and American empire, we really need to understand Masonry, and always to be alert for its presence.

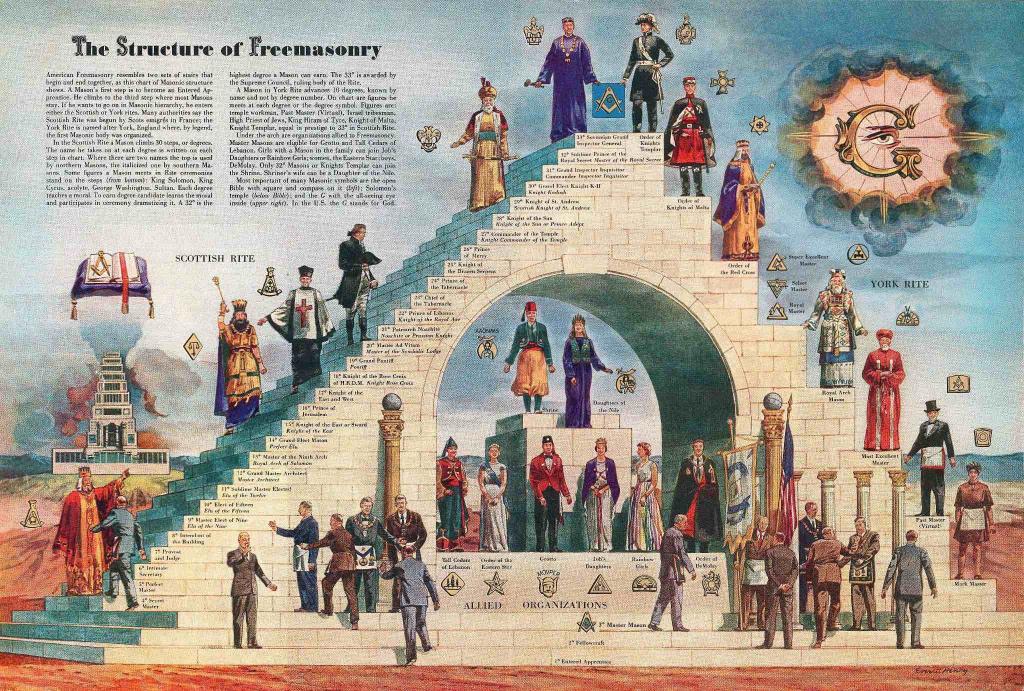

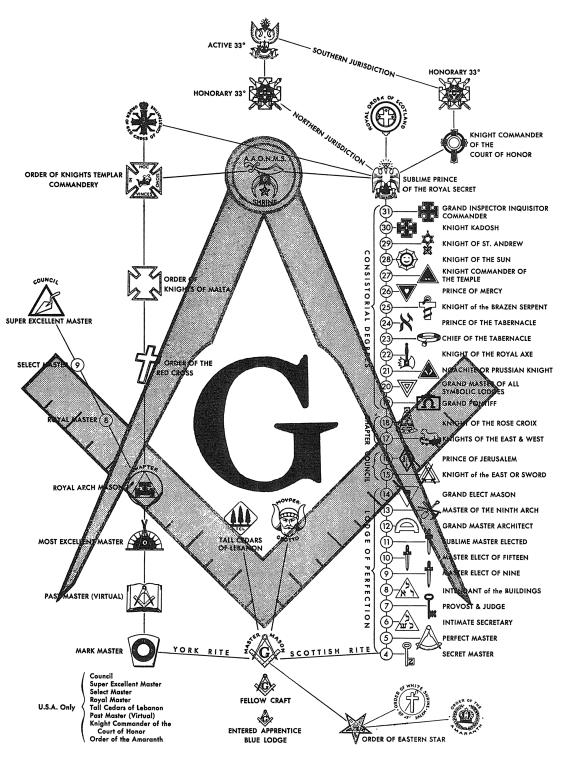

By way of background, Masonry evolved in seventeenth century Britain, emerging from the old world of craft guilds. In 1717, a group of lodges combined to form the Grand Lodge of London and Westminster, which what later became the Premier Grand Lodge of England. During the eighteenth century, the Craft became a popular vogue among elites, who relished its ritual and mythologies, and that appeal extended to aristocrats and even royalty. You couldn’t go far in British towns large or small in the late eighteenth century without running into Masonry, and its political impact was enormous. It was a central organizational force for the emerging professions – for doctors and lawyers, shopkeepers and merchants, and also for military officers. The legal profession was a particular stronghold, and in later years, the police. Protestant clergy were deeply involved. I sometimes describe the Anglican/Episcopal church semi-seriously as “the Masonic Order at prayer,” but other denominations were also highly active. Although it was theoretically open to any monotheist, its core appeal was to a non-sectarian Protestantism.

You absolutely cannot understand the British Empire without Masonry, and that includes the history of all former imperial territories, from Canada and Australia down. Masons were at every level of the government, the bureaucracy, and the armed forces. They sailed the ships, ran the banks and the newspapers, staffed the ranks of commissioned officers, and also ran plenty of the Protestant churches and missions. I suppose you could write the history of Anglo-American missionary endeavors without paying due attention to that Masonic context, but you’d be a fool to try. That was true from the end of the eighteenth century right up to the withdrawal from colonial empire in the 1950s and 1960s.

To get an idealized sense of that world of imperial masonry, read Rudyard Kipling’s Indian stories, and his poems like “The Mother Lodge”. Also, do watch the extravagant 1975 film of Kipling’s The Man Who Would be King, with Sean Connery and Michael Caine, especially the opening sequence in the train.

What about the United States? The Masonic presence among the Founding Fathers is very well known, from George Washington down, and at least nine of 56 signers of the Declaration of Independence were Masons. Masons remained a powerful fact in government and the military well into the mid-twentieth century. Plenty of Presidents have been Masons. But Masons were quite ubiquitous in the expanding empire, as the US conquered its continental territories, and subsequently spread into the Pacific and Caribbean. In 1969, the US even put a Freemason on the Moon, but that is another story.

As in Britain, all the mainline churches were heavily Masonic. You get a great visual sense of this in any small city when you walk through the prosperous old areas where the great churches stood – Presbyterian, Methodist, Congregational, Episcopal and the rest. And usually, right in the middle of those assemblages, you find the Masonic Temple. Episcopal clergy in particular were very likely to be Masons. This religious context is amply illustrated by Washington’s National Cathedral, commissioned in 1893, and built from 1907 onward, during the country’s high imperial age. Mason Theodore Roosevelt presided over the laying of the foundation stone, and most of the key fundraising was the work of Masonic general John Pershing in the 1920s. Masonic groups took a passionate interest in the venture at every stage. As Masonic writers proudly noted, the cathedral was in full view of “Washington Masonic Memorial (Freemasonry’s own national cathedral).”

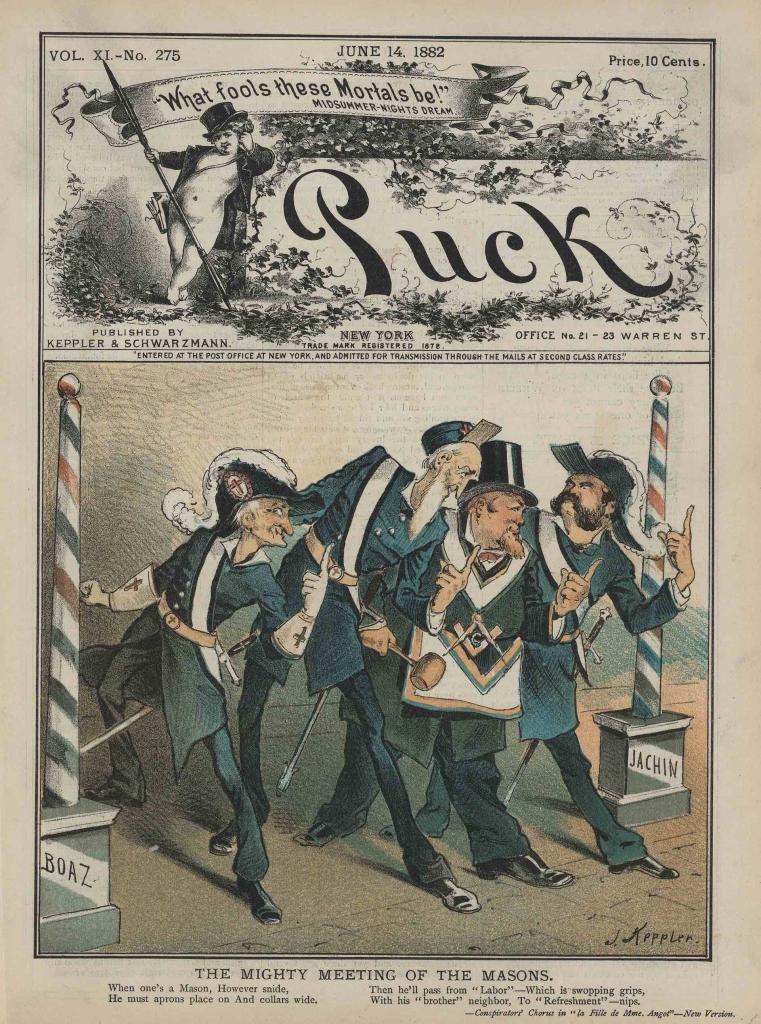

The numbers are impressive. The country had around three million Masons in the mid-1920s, although the Depression years saw some decline. A new boom began in 1948, and membership stood at or above four million from the mid-1950s through the mid-1960s. Not coincidentally, these numbers closely track trends in church membership, and in both cases the post-World War II boom is apparent. So is the subsequent contraction. Do recall that those numbers all refer to men, so we would need to add an appropriate multiplier to work out the total population of Masonic families. Including women and children, would that be around fifteen million or so individuals in 1960?

The expanding imperial frontier that we know as the Wild West was a Masonic West. That was true from the time of John Jacob Astor, the Grand Treasurer of the Grand Lodge, and the key organizer of the fur trade. Both Lewis and Clark were Masons. Later adherents included such legendary figures as Buffalo Bill Cody, Kit Carson, Pat Garrett, and Wild Bill Hickok. Crucial to the economic development of the West were cattlemen like Charles Goodnight and Oliver Loving, whose fictionalized story is the basis of Lonesome Dove. They belonged to a lodge in Weatherford, Texas, and when Loving died, Goodnight famously brought back his body to be buried with full Masonic honors. Freemasonry was the cement that bound together the Santa Fe Ring that was so crucial to the history of New Mexico and the Southwest. Among those who created the Western legend, Tom Mix, Gene Autry, Roy Rogers, and John Wayne were all Masons.

Why were Masons so central? Partly, the ideology fitted perfectly into the world of westward expansion, with its preaching of progress, development and improvement, all in the context of tough masculinity. This rational and inclusive religion of masculine-oriented reason provided a superb template for concepts of Manifest Destiny, the expansion of American power over what they saw as lesser breeds hidebound in their form of primitive effeminate superstition – whether practiced by Native Americans, Hispanic Catholics, or East Asians. But the practical appeal was evident, in a society marked by constant movement and enormous space. Who knew if next year you would be in Colorado or Oregon? But when you got there, you already had in place a network of brothers and supporters, who provided instant community.

By the way – are you interested in gender history? If you want to understand shifting ideas of American masculinity, put Freemasonry front and center in your research.

Never attempt to write Texas history without Freemasonry. All the heroes of the Texas Revolution were Masons – Davy Crockett, William Travis, Jim Bowie, and Sam Houston. So were all the famous Rangers, such as John B. Jones and Jack Hays.

The new Texas Republic created a great Baptist university named for its founder, Judge R. E. B. Baylor. His statue is a famous centerpiece of the campus at Baylor University, where I teach. Judge Baylor himself was a Mason from 1825 until his death in 1874. Most of his successors as heads of the university were likewise Masons, including Texas Governor Pat Neff. My own office is in Pat Neff hall, which was opened in 1938 with a Masonic ceremony to lay the cornerstone. Baylor’s seminary is named for George W. Truett, who was yet another Mason. For many years, the university’s mainstream culture easily integrated Baptist and masonic traditions, and there was no obvious tension between the two components. Both shared principles of self-reliance, independence, fraternity, benevolence, wide-ranging religious toleration, and ideals of Christian manhood.

“Freemasonry is the missing dimension in American evangelical history” (DISCUSS).

I mention one famous Masonic legend, and I stress legend. When the Mexican General Santa Anna was defeated at San Jacinto in 1836, the battle that gave Texas its independence, many of his enemies were anxious to kill him outright. Reputedly, he was saved by giving the Masonic distress signal, which had earlier saved John Wood, and which would carry immense weight with Sam Houston. Trivia point: when Texas founded the university that became Baylor, the original name proposed for the institution was San Jacinto.

I could, as they say, go on forever here, but that same Masonic appeal for aid did not save Joseph Smith when he was executed in 1844. Mormonism had a complex relationship with the masonic craft. They imbibed a lot of anti-Masonic mythology, but at the same time, they appropriated a good deal of Masonic symbolism for their Temple ritual.

The American imperial frontier without Freemasonry? Are you joking? But correct me if I am wrong here: does a single Western film reflect this, or show a Masonic ritual? I can only think of a couple of references offhand. One is a character wearing Masonic symbols in the 1993 movie of Tombstone. Also, in John Sayles’s wonderful movie Lone Star (1996) the evil sheriff played by Kris Kristofferson wears a Masonic ring. But given the many thousands of films in this genre, that is slim pickings. Lone Star actually has a modern Western setting.

American imperial interests often turned further afield, into the Pacific, the Caribbean, and Central America. In many areas, the bulk of the population was Catholic, and was therefore anathema to Masonic ideology. Catholics heartily reciprocated this loathing, holding as they did a range of florid anti-Masonic conspiracy theories. By 1917, a Catholic who joined a Masonic Lodge faced automatic excommunication. In some areas, tension was lessened because local elites themselves were heavily Masonic and anti-clerical, especially in the military: in Mexico, again, think Santa Anna.

Real conflict came in the Philippines, after its conquest by the thoroughly Masonic-officered forces of the US Navy and Army, under the orders of a sequence of Masonic Presidents – McKinley, Teddy Roosevelt, and Taft. The Department of the Pacific in the early years of the Philippine War was headed by Freemason Arthur MacArthur, whose son Douglas MacArthur also became an enthusiastic Mason. The younger MacArthur arrived in the Philippines in 1903.

The Philippine population was heavily Catholic, and deeply restive under the Protestant and Masonic American ruling elite, and the local Masonic allies they coopted to rule the new imperial possession. In 1924, Philadelphia’s Catholic Cardinal Dennis Dougherty protested that

There is a conspiracy to kill Catholicity in the Philippines. Our Government has consistently worked hand in hand with the Y.M.C.A., Bishop Brent and other Protestant organizations. Free Masonry is rampant, open, and hostile to the Catholic Church in those Islands. The Masons have a grip on things there to an extent which is unbelievable if not seen.

Bishop Brent – the missionary bishop of the US Episcopal church – was a frequent target of such complaints. It was in the Philippines especially that imperial Freemasonry ran most directly against the older religious establishment.

More shortly on Masonic themes.

I should explain my own personal interest here. I have never been a Mason, but my father was a very enthusiastic (and senior) adherent. My first published academic article ever, back in 1979 (!) was on Masons. I specifically discussed the overlap between Jacobites and Freemasons in eighteenth century British politics.

SOME SELECT REFERENCES

Steven C. Bullock, Revolutionary Brotherhood: Freemasonry And The Transformation Of The American Social Order, 1730-1840 (University of North Carolina Press, 1996)

William S. Cossen, Making Catholic America: Religious Nationalism in the Gilded Age and Progressive Era (Cornell University Press, 2023)

Lynn Dumenil, Freemasonry and American Culture: 1880-1930 (Princeton University Press, 1984, reprinted 2014)

Kyle A. Grafstrom, Freemasonry in the Wild West (Plumbstone, 2017)

David G. Hackett, That Religion in Which All Men Agree: Freemasonry in American Culture (University of California Press, 2014)

Michael A. Halleran, The Better Angels Of Our Nature: Freemasonry In The American Civil War (University of Alabama Press, 2010)

Jessica L. Harland-Jacobs, Builders of Empire: Freemasons and British Imperialism, 1717-1927 (University of North Carolina 2007)

Peter P. Hinks and Stephen Kantrowitz, eds. All Men Free and Brethren: Essays on the History of African American Freemasonry (Cornell University Press, 2013)

Michael W. Homer, Joseph’s Temples: The Dynamic Relationship between Freemasonry and Mormonism (University of Utah Press, 2014)

Dana W. Logan, Awkward Rituals: Sensations Of Governance In Protestant America (The University of Chicago Press, 2022)

Joy Porter, Native American Freemasonry: Associationalism And Performance In America (University of Nebraska Press, 2011)

I note this important 2023 exhibition at the Scottish Rite Masonic Museum, which tells “the story of American Freemasonry in the Panama Canal Zone during the era of American imperialism in the early twentieth century.”

On a different topic that should be of great interest, do check out this splendid upcoming virtual conference on Evangelicalism and Missions: Studies in the History of the Spread of the Gospel