I love the story of an underdog. I find myself drawn to histories and narratives of folks who were disadvantaged but made good anyway. I’m not sure if it is particular to U.S. culture, or if it is connected to the mythologies scholars have noticed transcend geography, but it does seem that many of us enjoy the heroic narrative of the little guy (usually an actual male) making good and coming out triumphant over their enemies or obstacles. We associate victims and virtue.

It’s even tempting to teach history this way. To look out for those who overcome, who had few advantages and still succeeded. We might tell our national histories this way, focusing on the way political or military leaders rallied the people to overthrow the oppressor and break through into the glory of our current state, after surmounting some certain difficulties along the way. I find myself tempted to teach about the Reformation in this way as well—oppressed religious groups being persecuted and then finally rising above their circumstances to create new thriving churches of their own. It works for civil rights movements, scientific endeavor, individual narratives, travel/immigration history, etc.

This allows us to have heroes—but very often heroes who were also victims of other people or circumstances at some point in their lives. And often we conflate the status of victimhood with virtue. Frequently it appears that very identification of a person or people as oppressed directly confers virtue on the underdog or victim. Those seen as oppressing are automatically the bad guys and the victims the good guys.

There are good reasons for feeling this way. Often power does result in domination, with the de-humanizing and evil effects that the ability to control and coerce contains. And as a Christian, I see Jesus as being on the side of the weak and oppressed. I tell my students that when we look for God in history, this is where God will be—with the “least of these.”

However, increasingly scholars are also studying what it means to associate virtue with victimhood. It has effects both personally and socially. It may mean that young people look to take on identities that they connect with the underdog, those who are martyred by the larger society in some way, because those identities appear to be “better” than recognizing one’s connection with the systems of power.

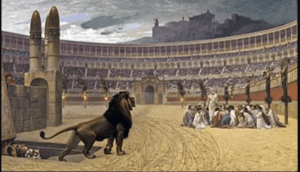

As Christians, we have a long history of allying ourselves with the martyrs, seeing them as the quintessential Jesus followers. It is disturbing sometimes to my devout Christian students, to find that early Christians in the Roman Empire might not have been as unrelentingly persecuted as the stories they grew up with would have predicted. The picture of a strong and unrepentant Christian facing a lion in a colosseum in the second century is a powerful metaphor for how Christians consistently saw themselves.

In fact, when Christianity became too “easy” and the majority religion of the empire, the stories of martyrs and the reading/telling of saints’ lives who suffered for their faith became an important element of Christian devotion. They needed to be reminded of how following Jesus meant suffering and not being on the side of the powerful—though most of the powerful in the Mediterranean world were in fact Christian by the fifth century. Eventually, those who wanted to suffer for Jesus formed communities that separated from the world and took vows that would ensure they suffered—monks and nuns were the result of people deciding that when everyone is a nominal Christian, “real” Christians need to find ways to follow the path of Jesus outside of societal norms.

But does suffering itself ensure virtue?

This connection can have multiple problems. First, it can prevent people from seeing the ways that even the oppressed have the opportunity to dominate others in their turn. If I think of myself as the one being attacked by others, I may revel in that, and not notice my own petty tyrannies. Second, feeling victimized can prevent me from acting in ways that promote my own agency. I see this occasionally with my students, who feel overwhelmed by their disadvantages and therefore unable to move forward in any way. The stories of the little guy making good are often intended to counter this lethargy and discouragement. “Pull yourself up by your bootstraps!” “Look at how this group just organized and overcame and were successful by working hard enough!” My young and beleaguered students need these stories.

But for some of us who are older, such stories feel trite. We feel exhausted and discouraged by how hard it is to overcome and triumph. The old hero narratives don’t seem to apply to us. Perhaps we know we aren’t that virtuous even if we are harassed and our best efforts fail in the face of power structures. Being a victim or a martyr doesn’t seems to apply to us, but also we don’t recognize ourselves in the face of dominion. Or maybe we want to claim the virtue that comes with being the underdog just because it feels like we will never overcome. We need more complicated histories, accounts of those who had complex lives, in which they exerted their tiny bits of agency in the corner of the world they were in, even while they lived in webs of control and social structures they couldn’t radically change.

For Christians in the United States today, being told that we are the problem, that we have been the oppressors, feels like a slap in the face. If we aren’t the victims of power, can we have any virtue? We are tempted to look at the ways in which it feels like society is coming after Christians, is attacking them in public, to point out ways in which Hollywood or social influencers or higher education are condemning us as the villains of history. The seduction of calling on our status as victims is understandable. We have a long history of wanting to be on the side of the martyred, not the powerful.

But in fact, the line between those two sides runs down the center of all of us. We have the ability to be tyrants with those in our sphere, even as we are in fact small cogs in the political, economic, and social structures of our world. We do in fact need stories of those who have overcome anyway, but we need to re-think what that “overcoming” might look like. It might not mean “winning” in the traditional political or economic definitions. And the fact of victimhood does not confer automatic virtue. Jesus is with us when we feel oppressed, but he nudges us to think about when we are lording it over others.

For all of us wanting ways to think about biblical ways of navigating our space in the webs of power, I commend the Sermon on the Mount, and especially this reminder that we all have spaces where we have advantages as well as handicaps. History is best when it shows us people who with all their moral frailty had to live in the in between: “If someone strikes you on the right cheek, turn to them the other also. . . Give to the one who asks you, and do not turn away from the one who wants to borrow from you. . . Love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you. . . God sends the sun to rise on the evil and on the good.”