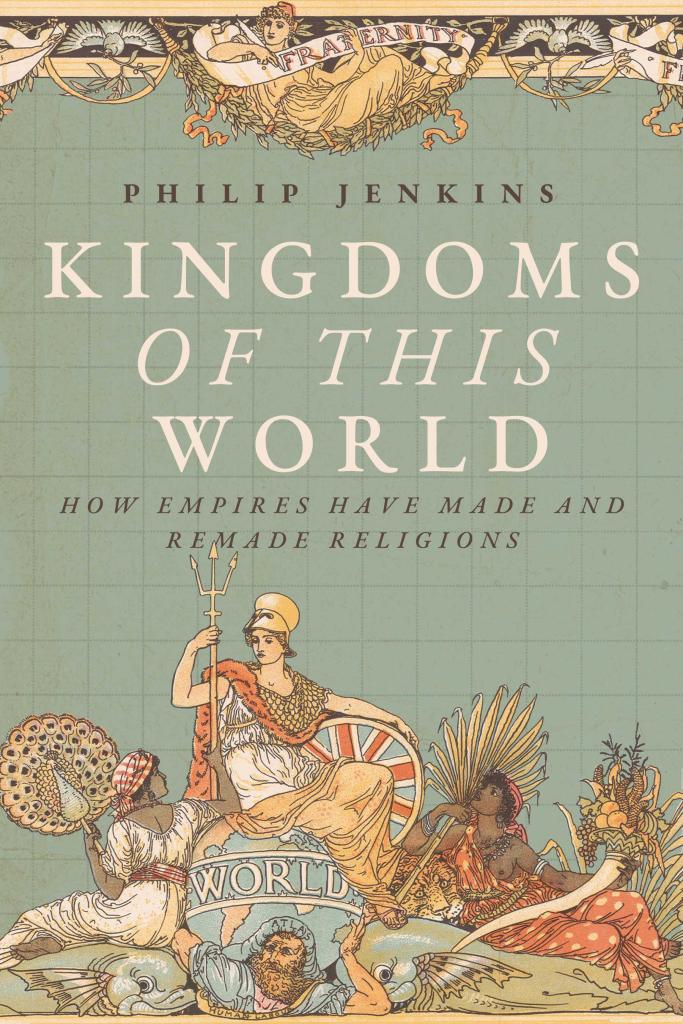

My last post explored how America’s imperial expansion reshaped its attitude to other religions, which were commonly viewed according to some grim racial stereotypes. Specifically I looked at how visions of Voodoo affected views of Black Americans, and that stereotype extended to Black variants of Islam. In fact, there is a lot more to say about those imperially-formed visions of Islam.

The American encounter with Islam must be seen in the larger context of the European imperial project, which for much of its history involved the subjection of Muslims. When the British arrived in India, most of the subcontinent was subject to Islamic states and empires. Russian expansion to the south and east was usually at the expense of Muslim neighbors, and the French plunged into North Africa. The decline of Islamic political power accelerated sharply from the 1850s onward, with the British suppression of the Indian Mutiny and the termination of the Mughal dynasty. Meanwhile, Persia came under the shared hegemony of Britain and Russia. Europeans progressively absorbed Ottoman lands, as Westerners (including Americans) pushed to establish Christian missions and schools throughout Islamic territories.

At the start of the twentieth century, the vast majority of the 240 million Muslims worldwide lived under European rule. The British Empire was what Sir John Seeley termed “the greatest Mussulman Power in the world,” with some seventy-five million Muslims in the Indian sub-continent, in addition to twenty-five million more in Africa and the rest of Asia. By 1914 the Dutch East Indies was home to perhaps forty million Muslims. Russians, French and Spanish all ruled large Muslim populations.

Many of the pivotal episodes in the military history of the European empires involved confrontation with Muslim forces. Muslim forces often rebelled against the empires, and Europeans duly interpreted such resistance as signs of unreasonable fanaticism. At the start of the twentieth century, the British and other nations were locked in a vicious and prolonged war against the Somali Muslim leader they knew contemptuously as the Mad Mullah, whose alleged madness consisted of his not wishing to succumb to imperial rule. For the US, joining the club of imperial states meant coming to share their experience of viewing Muslims as deadly enemies, to whom were attached all the familiar stigmas of fanaticism and obsessive violence.

Conflicts with Islamic powers were nothing new for Americans, as the first military efforts of the newly created nation were directed against the so-called Barbary states of North Africa. But wars renewed at the end of the nineteenth century, and so did religious hostility. Surprisingly to even Americans who know something of history, that religious angle was very prominent in the Philippine War, and especially the several years of brutal counter-insurgency that followed the defeat of Spain in 1898. The great majority of the country’s people are of course Catholic, but sizable Muslim populations thrive in southern regions such as Mindanao.

American forces counter-insurgency operations here reached a horrifying climax in 1906 with the savage massacre of (at least) hundreds of Moro people at Bud Dajo, Jolo. That chilling episode is now the subject of Kim A. Wagner’s powerful book Massacre In The Clouds: An American Atrocity And The Erasure Of History (PublicAffairs, 2024). As the title suggests, the book is as much about the national failure to recall such things as about the massacre itself.

The great majority of the dead were Muslim, and of course, in American eyes, they had thoroughly deserved their fate. I quote from Adam Hochschild’s review of Wagner in the TLS (paywalled):

One theme that runs through Wagner’s book is how contemptuous the Americans were of the Moros’ faith. A newspaper headline spoke of “Mad Moros Killed”; [Major General Leonard] Wood himself called them “pirates and highwaymen”. An American machine-gunner at the crater wrote home about “the delusion that the Filipinos and Moros are actually human beings”. They were seen as “fanatics” who were, in a phrase picked up from British descriptions of Malays, “running amok”. “Civilization has to be shot into them”, wrote an American captain. A colonel declared that he had “decided that perhaps the best way to impress the lesson of lawfulness upon the natives was … by burying their bodies with a hog”.

I have posted in the past about Edgar Lee Masters’s wonderful poetry collection, The Spoon River Anthology (1915), which tells the social history of the era in the form of vignettes of the residents of a small Midwestern town. Harry Williams was a young man who joined the forces when he heard a patriotic preacher declare that

“The honor of the flag must be upheld,” he said,

“Whether it be assailed by a barbarous tribe of Tagalogs

Or the greatest power in Europe.”

Harry predictably meets his end, shot near Manila by those “barbarous Tagalogs.”

As so often in the high imperial era, ruling nations freely shared stereotypes. For Americans as for the British, Muslims who resisted were “mad,” “barbarous,” and tended to “run amok.” Not, of course, that Americans needed too much assistance in forming such ideas. By this point, they had over two centuries of Indian Wars behind them at home, and the Wounded Knee massacre of 1890 was a very recent memory. In White American eyes, that episode grew out of the “fanaticism” of the Ghost Dance movement. In reality, Haitians and Moros and Lakota shared very little in terms of their religious beliefs and practices. But in the eyes of the conquerors, they all merged into one common pattern of the primitive, bloody and fanatical, and almost indistinguishably so.

For Americans as for Europeans, the imperial experience profoundly shaped views of the religions of the peoples they tried to subjugate.