Empires affect religions and religious life in many ways, often unintentional, and the American empire was no different from its counterparts.

I have described how, on occasion, metropolitan populations are influenced by the religions of subject peoples, and actually adopt them. But a quite different response was also possible, namely that ruling groups are appalled and disgusted by what they encounter on the frontiers of empire, and that reaction affects their attitude to quite separate kinds of religious behavior. Stereotypes formed on those frontiers come home, often with grim consequences. In the nineteenth century, the British were alarmed by the concept of homicidal “thugs” in India, and that idea became a familiar part of the language of prejudice with which elites viewed the lower classes and, later, other races. Moral panics about domestic violent crime in Britain itself (committed by lower class White people) focused on the nightmarish figure of the “thug.” In modern times, Bill Buford did a notable book about British football violence called Among the Thugs: The Experience, and the Seduction, of Crowd Violence (1990). If you watch the classic 1939 film Gunga Din, you see how that horrible image of thuggee shaped Western views of “Oriental” faiths, including Islam as much as Hinduism. That film had an enormous cultural influence, which shows up in many later productions, including Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom. Of course, it is hotly debated whether anything like thuggee ever existed as a historical reality.

What the British empire did with thuggee, the American empire did with “Voodoo.”

From early national times, Americans had been deeply interested in Caribbean expansion, and in the early twentieth century, the growing empire expanded its power with occupations of Cuba, Haiti, Nicaragua, and the Dominican Republic. The country formally acquired Puerto Rico and the US Virgin Islands. All these encounters had their consequences, but in religious and cultural terms, the prolonged military occupation of Haiti (1915-1930) was very significant. As white Americans observed the country’s authentic and deep-rooted Voodoo/Vodou, they struggled to comprehend it, and the extremely hostile picture they formed could not fail to affect visions of Black culture and religion in the homeland.

American stereotypes of Voodoo predated the imperial occupation. In 1884, a study of Hayti; or, The Black Republic portrayed the Voodoo religion in terms of human sacrifice and rampant cannibalism. In 1908, the Metropolitan Magazine reminded American readers of the Haitian horrors, especially the idea of the ritual sacrifice of a young child, known as the “goat without horns.” But such ideas became very widespread during the occupation of the 1920s, and they achieved canonical status with William Seabrook’s The Magic Island (1929), which set the tone for all later writings on Voodoo. He introduced the mass American audience to such technical terms as the houmfort (mystery house, or temple), and his book brought the word “zombie” into the English language.

Seabrook quoted extensively from Voodoo rituals, describing ceremonies which are not only bloody, but also involve a powerful sexuality, with elements of perversion and bestiality: Haitians were presented as a “blood-maddened, sex-maddened, god- maddened” people. The book stresses themes of fear, death and bloodshed, of death curses, zombies and animal sacrifice. Racist theorists of the era – and there were plenty of those – regularly argued that this was simply the natural form of African primitivism and fanaticism, whenever the restraining hand of White rule was removed.

Images of voodoo pervaded American popular culture., and naturally, the emphasis was always on the savage, primitive, and bloodthirsty. Zombies became a recurring element in horror films like White Zombie (1932) and its many B-film imitators, all of which drew ultimately from Seabrook. There was also the more serious treatment in Val Lewton’s brooding and atmospheric 1943 film I Walked with a Zombie.

These tropes ran riot in the remarkable pre-Code film, Black Moon (1934), which is notable today for the starring role of Fay Wray. A young White woman returns to the Caribbean island of “St Christopher” where her parents had been killed in a Voodoo ritual, and she herself is gradually drawn in to an obsession with the cult and its rituals, to the point of agreeing to sacrifice her daughter. Although the island is fictitious, the fact that the Natives speak French Creole means that it must be meant to be Haiti. The film depicts the rituals in some detail. Her husband’s attempt to rescue her persuades the Natives to massacre all White people on the island. Ultimately, the husband himself kills Juanita to save their daughter. The film’s advertising poster proclaimed “Love battling against the sorcery of the jungle!”

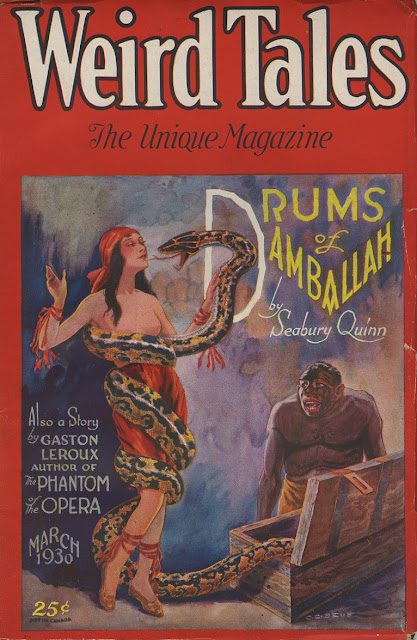

The legendary pulp magazine Weird Tales had lots of Voodoo-related material. It featured stories by the excellent supernatural author Henry S. Whitehead, an Episcopal cleric who bore the splendid title of the Archdeacon of the Virgin Islands from 1921 to 1929: he was friendly with H. P. Lovecraft. In 1930, Weird Tales published the story “Drums of Damballah” by Seabury Quinn, one of its most popular authors. The story depicts a lethal and very widespread Voodoo cult operating in New Jersey, where it seeks to sacrifice a young White girl as a “goat without horns.”

That focus on Haitian-style Voodoo encouraged American writers to impose that vision on the country’s own domestic Hoodoo, with its (very different) African-derived magical practices. Even Zora Neale Hurston describes her elaborate initiation at the hands of several New Orleans Hoodoo doctors, in ceremonies which involved the sacrifice of sheep and chickens. At times, she seems to confirm the reality of the organized Voodoo myth, speaking of “rites that vie with those of Haiti … deeds that keep alive the powers of Africa.” In Mules and Men, published in 1935 at the height of the demonization of Voodoo, she declares that Hoodoo “or Voodoo, as pronounced by the whites, is burning with a flame in America, with all the intensity of a suppressed religion. It has its thousands of secret adherents … It is not the accepted theology of the Nation, and so believers conceal their faith.”

On the other hand, she stresses the individual work of spells and conjures in Hoodoo, and mocks the “Voodoo ritualistic orgies of Broadway and popular fiction … drum-beating and dancing.” Her ambiguity reflects the mixed feelings felt by educated Black Americans towards the Voodoo mythologies. In 1938, her Tell My Horse offered a study of African-derived beliefs in Haiti and Jamaica. Though intended as a celebration of African culture, the book encouraged the idea that Black Americans were likely to be involved in savage rites.

This fascination with supposed Black primitivism and jungle savagery had real world consequences. By way of content, the interwar years witnessed an upsurge of Black religious experimentation in the US, usually in radical and sectarian forms, sometimes marked by racial nationalism and separatism. This was the age of Garveyism, of Black Islam, the Moorish Science Temple and the Nation of Islam, of Black Jews, and of popular messianic movements like those of Father Divine and Sweet Daddy Grace. All, to varying degrees, were now interpreted through the lens of Voodoo, however bizarre such a juxtaposition might sound.

The Nation of Islam (NOI) attracted deep suspicion, and it may actually have been involved in clandestine killings. Between 1932 and 1934. Detroit’s Black clergy launched a fierce attack on the “fanatical teachings and barbarous practices” of the Muslim cult, and urged police to combat “the sinister influences of Voodooism [sic].” A less suitable parallel could scarcely be imagined, given that Voodoo and Islam are located at opposite ends of the religious spectrum in terms of their attitude to divinity, and the nature of religious practice. Still, in the thought-world of the time, any autonomous Black religion was assumed to be Voodoo-related, with all that implied about primitive violence, human sacrifice, and orgiastic sexuality.

The Detroit Free Press used the term Voodoo in virtually all its stories about the NOI movement in these years, with headlines like “Negro Leaders Open Fight to Break Voodooism’s Grip,” and references to a “Voodoo Altar Slaying.” Police intervention drove Black Muslim activities underground and resulted in the arrest of founder Wallace Fard. By 1933, the Detroit Free Press could declare that “Voodoo’s Reign Here is Broken.” Fard’s successor, Elijah Muhammad, was himself arrested in 1934 for “contributing to the delinquency of a child, and Voodooism.” When in 1937, the prestigious American Journal of Sociology published a scholarly account of Black Muslim origins in Detroit, it did so under the bizarre title of “The Voodoo Cult Among Negro Migrants in Detroit,” discussing “The Nation of Islam, usually known as the Voodoo cult.”

The insistence on seeing black religion as forms of Voodoo extended beyond the Muslims. When a group of white Columbia University students attended one of Father Divine’s services, they anticipated “an evening’s entertainment consonant with popular ideas of African fetish or Haitian Voodoo worship.”

What happens in the empire does not stay in the empire.

I discussed these issues at some length in my book Mystics and Messiahs: Cults and New Religions in American History (New York: Oxford University Press, 2000), from which many of the references here are taken. See now Danielle N. Boaz’s rewarding book, Voodoo: The History of a Racial Slur (Oxford University Press, 2023).

I reserve for a footnote a nice self-mocking reference to White American attitudes on these matters. In the classic Busby Berkeley dance/musical Flying Down to Rio (1933), Fred and Ginger find their plane forced down on a Caribbean island, which turns out to be Haiti. They are very nervous to see Black faces peering at them through the jungle edge, and are naturally terrified of what might happen. One of the local men then introduces himself in impeccable upper crust British English and explains that the young men all work at the local country club, and today is the caddies’ golf tournament. The speaker is played by Clarence Muse, a theatrical star of the Harlem Renaissance.