Welcome, new year! By the end of 2016 it had become a little too fashionable to express relief that that wretched year was over. But just turning a calendar page is cheap satisfaction, since lots of the trouble we carried in the previous year comes sloshing over into the new.

Among those troubles, the trial of Charleston shooter Dylann Roof stretches on. Just before year’s end, Roof, convicted of killing nine people at Emanuel A.M.E Church in Charleston in June 2015, was ordered to undergo another competency evaluation. Now declared competent for sentencing, with the death penalty at stake, painful recollection of the crimes continues.

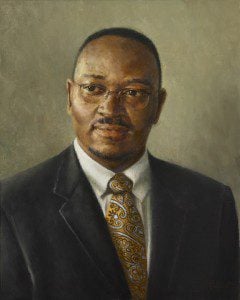

One way of stirring hope within the bleakness of our midwinter may come from reforming the way we look at each other. In the context of the Charleston shootings, alongside the sorrows reprised through the trial, at least one event helped nurture such hope. Last spring the Emanuel Nine Tribute-A Portrait Project sought a way to honor those nine lives lost. Under leadership of artist Lauren Tilden, nine different artists were engaged, each to do one portrait. The portraits were shown at the Principle Gallery Charleston in May and then given to victims’ families. Catherine Prescott, a distinguished painter from Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, painted the pastor, Rev. Clementa C. Pinckney.

In her distinctive portraiture, Prescott insists on a truth that sometimes gets stinted: that a portrait can and should show something of the interior life of the subject in a way that makes possible some real understanding of that person. That assumption, in painting and sculpture for long centuries, traditionally has animated great portraits of saints and sinners alike.

Discussing her work, Prescott presses back against distortions of the genre, distortions abetted variously by art trends, by a social-media milieu that grasps after fleeting snaps, and by infinitely malleable appearances that belie the existence of a real person underneath. Portraits can help us see. As Prescott explained in a July conversation:

I think the most awful feeling is that of being alone, and only Scripture can teach us fully and convincingly that we truly are not alone. But art can be expressive and personal and full of feelings; it can point us to new ways to understand our own longings, and offer us something outside of ourselves. Insofar as it does this well it may be able to help people, the viewers of the work, to know they are not alone. If art is to do this it needs to be the opposite of what social media teaches us. Social media suggests to us that we are left behind, that the world is passing us by, that everyone else is having fun and being brilliant and on the cutting edge, with pictures to prove it, and we have to drum up something new to boost our selfness….In the context of Principle Gallery Charleston’s beautiful hanging of the nine works, the church members and the families seemed to receive that idea, that their loved ones were being not just remembered or even honored but that they were specific, loved individuals and that we were all connected to each other.

Much 2016 handwringing, especially through November but not only then, centered on the difficulty, even seeming impossibility, of recognizing people—fellow citizens, refugees, enemies—as “specific, loved individuals with connections to each other.”

As a New York Times new-year’s editorial opined, we might turn around our bad year by showing “unflinching kindness” for “those who are marginalized and poor and weak.” True, but our efforts to lift others up must start with seeing. Doing this, it seems to me, begins with a gesture like that enacted in the Emanuel Nine portrait project. Thinking in the way Prescott advises, a way that helps us see a face and receive the whole of the person shown therein, is a spiritual discipline worthy of the year that comes after 2016. Really thinking that way when we go about our days—when we see the news or pass a neighbor or go to work or wait in line—may help us stretch hope in this new year, still trailing the troubles of the last.

The Honorable Reverend Clementa C. Pinckney

Oil on Canvas

20 x 16”, 2016

I