It sounds better coming out of Tim Challies than me: “One of the great weaknesses of the contemporary church is its detachment from its own history.” After all, it’s one thing for a history professor at a Christian college to make that claim. It’s another when one of the top 10 Christian bloggers writes it. So I’m grateful to Challies for urging his substantial readership to seek a better grounding in the past:

There are many reasons we ought to teach believers their history. History gives us purpose. History gives us hope. History gives us theological grounding. But as much as anything, history reminds us that we live in the shadow of those who have come before and that those who follow will, in turn, look back to us.

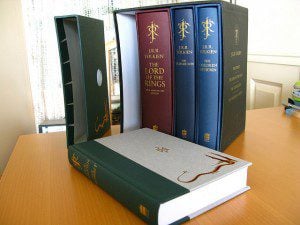

Here he’s been inspired not by reading history, but fantasy: the Lord of the Rings trilogy, whose characters “know they are set within a wider drama that began ages prior and will continue ages hence. They are determined to act in ways that honor their forebears and leave a worthy example for their descendants.” But Challies thinks there’s an application for the historic, not just imagined, past:

We’d do well to learn from their example. We, too, need to set believers within their history. We, too, need to teach them they are small but significant players in a much wider, grander drama. They must always be aware of those who have gone before and always think of those who will follow. They do not stand alone in the story, but always in the shadow of their forebears. What Tolkien did so well is what we do so poorly.

If that’s going to motivate American Christians to set themselves better “within their history,” then I’m all for it.

But it’s not the only benefit of studying history. So, knowing that Challies was not trying to make a comprehensive case for our discipline, I thought I’d take a shot at listing 5 more reasons we ought to teach believers to think historically about their past.

History teaches us how to ask questions

Note that I’m tweaking Challies’ starting point here. Much as I want to turn fellow Christians’ attention back in time, there are many ways of understanding the past — and I’m not sure that the wishful thinking of nostalgia or unthinking clinging to tradition is any better than sheer disinterest. What matters more to me is that Christians learn to think historically about their past.

If that happened, I think the first thing you’d notice is that Christians would be better at asking questions. They’d be less prone to assuming things are as they always have been and instead wonder what happened to cause changes over time. They’d be better at looking beyond first impressions and initial misunderstandings. They might even ask harder questions of those in power — and listen harder for the voices of those without power.

If that happened, I think the first thing you’d notice is that Christians would be better at asking questions. They’d be less prone to assuming things are as they always have been and instead wonder what happened to cause changes over time. They’d be better at looking beyond first impressions and initial misunderstandings. They might even ask harder questions of those in power — and listen harder for the voices of those without power.

History even helps us to ask questions we might think belong to theologians and philosophers: Who am I, and who should I be? What is the good life? What is my responsibility to others? What makes for healthy communities? Maybe even, Why does a good, all-powerful God permit evil and suffering? History can’t always answer those questions — but it prompts us to wrestle with them as they’re embodied in human experience.

Often, history offers safer ground on which to ask some such questions. I go to a church, for example, where clergy and laity very rarely talk out loud about politics. There are good reasons for that, but this reticence does make it harder for us to have necessary conversations. So when I had a chance last month to teach an adult Sunday School class, I suggested “The Church in the Wars of the 20th Century.” That topic inevitably raises essential questions about Christian citizenship (e.g., what allegiance Christians owe to their nation or state?), but in such a way that the risk of disagreement or conflict — or of changing one’s mind — doesn’t feel so daunting.

History teaches us to seek truth – and be comfortable with complexity

Thinking historically not only trains us to ask good questions, but to seek better answers. As historians like Joanne Freeman have been arguing in recent weeks, historical study requires evidence-based investigation, analysis, and evaluation — skills that readily transfer to life in a supposedly “post-truth” world full of “fake news” and “alternative facts.” (And of late, inevitably, “alternative history.”)

7/ And in teaching people to evaluate evidence in search of facts, it trains them to logically analyze & interpret news for themselves.

— Dr. Joanne Freeman (@jbf1755 on lots o’ platforms) (@jbf1755) March 6, 2017

But historical thinking also prepares us for answers that aren’t as cut and dry as we’d prefer. History is full of contradictions and exceptions, loose ends and non-sequiturs. To practice that kind of thinking requires comfort with inconvenient complexities like particularity, dissonance, and paradox.

How could it be otherwise? History is about humans. It’s a science that studies “molecules,” my graduate advisor once put it, “with minds of their own.”

There’s a strong impulse within Christianity to want to believe that truth is actually quite simple. And sometimes it is. But if the essentials of biblical faith are perspicuous, the world as we experience it is rarely so clear. If we don’t train our minds to be comfortable with complex truths, our ears will itch to hear simplistic falsehoods.

History teaches empathy

And make no mistake: deceptive simplicity is all around us. We walk in historical shadows that are shades of gray, but we step into a future that is increasingly presented in black-and-white terms. On issue after issue, there’s pressure not only to pick a side, but to condemn others to the “wrong side of history.”

But at a time when political, cultural, intellectual, demographic, and technological forces are segregating like-minded from like-minded, thinking historically expands the very definition of neighbor, so that it spans time as well as space. History teaches us to listen to those we might want to dismiss as enemies, to remember that those eyewitnesses to the past were fellow human beings whose vanished lives leave behind traces of the divine image they bore. For long moments, history even strands us in “a foreign country” and lets us feel what it’s like to be aliens and strangers.

But at a time when political, cultural, intellectual, demographic, and technological forces are segregating like-minded from like-minded, thinking historically expands the very definition of neighbor, so that it spans time as well as space. History teaches us to listen to those we might want to dismiss as enemies, to remember that those eyewitnesses to the past were fellow human beings whose vanished lives leave behind traces of the divine image they bore. For long moments, history even strands us in “a foreign country” and lets us feel what it’s like to be aliens and strangers.

In short, the discipline of history remains an engine of empathy.

History teaches prudence

But it’s not enough simply to think about our neighbors in time and thereby to feel greater love for others; if we come to love kindness, we must take the next step and also seek to do justice. For as much as I enjoy studying the past for its own sake, I’m also convinced that thinking historically cultivates a certain approach to Christian activism.

I can’t put it better than our Anxious Bench colleague Tal Howard: “We are not, and can never be, in Nietzsche’s felicitous phrase, ‘spoiled idlers in the garden of knowledge’ but are always already participants in ‘life’— a wonderful, tragic, complex, hopeful moral life.” To think historically, therefore, prepares us to live prudently, with a “hesitant seriousness” that encompasses both “the filter of reflection, and yet also the daring courage for definitive resolution.” We neither rush to action, refusing “to acknowledge the full complexity of the past,” nor “[tumble] uselessly into futility, into moral paralysis or jaded amoral sophistication” (“Virtue Ethics and Historical Inquiry,” in Confessing History, pp. 92-93).

History teaches humility

But we do all of this knowing that we do it imperfectly. We do justice and love kindness, but we also walk humbly with God. To do otherwise would be to deny one of our faith’s many paradoxes: that the saints remain sinners. After all, if history is a story of divine redemption, it’s because it’s also a story of human depravity. Our chapter of it will be no different.

Tolkien’s heroes may be “determined to act in ways that honor their forebears and leave a worthy example for their descendants,” but I’m glad Challies acknowledges that determination doesn’t always lead to success: “They speak and live as if every word of the mouth and every tap of the hammer will honor or dishonor those who have gone before and shame or bless those who will follow.”

Challies wants to exhort us to live honorably and so bless our descendants. May it be so! But we also need to carry a different weight of history: the awareness that some of what we do now will shame — or baffle or enrage — the Christians who follow us. How do we know? Because some of what our Christian forebears did ought to shame — and baffle and enrage — us, their descendants. We walk in that shadow of the past, and in the process, we cast our own shadow into the future.

So study history and so learn to ask questions, seek (complicated) answers, feel empathy, and act prudently. But do all these things in humility, by the grace of the One whose power is made perfect in our weakness.