When I ask students to read and generate questions about the Gospel of Mark, someone always asks about the beheading of John the Baptist? What sort of mother asks her daughter to ask her father for a prophet’s head?

(I can also count on a question about the fig tree, for which I never have an adequate answer).

According to Mark, John the Baptist criticized Herod Antipas for having married Herodias, his brother Philip’s wife. Just to be clear, the brother had not died. The king had taken his wife, an act obviously forbidden by the Torah. The wife in question wanted John killed, but Herod respected John. In order to silence John and mollify his new wife, he ordered John’s arrest, but liked to chat with him.

When Herod gave a banquet, his daughter (also named Herodias according to Mark) pleased Herod so much with her dancing that he offered to give her whatever she desired. Many readers presume that Herod was as infatuated with the daughter as he had been with the mother. The daughter consulted her mother, who told her to ask for “the head of John the Baptist on a platter.” The king did not want John dead (in fact, it seems he would have preferred to have fulfilled a rather different sort of desire), but he acquiesced. The girl then handed it over to her mother.

In his Antiquities, the historian Josephus confirms the story about the shady marriage, and he adds that Herod Antipas hatched a scheme to divorce his first wife at the same time. Joseph provides a different name for Herodias’s first husband and names their daughter as Salome. Josephus confirms that Herod had John killed, though he provides scant detail.

While Matthew more or less repeats Mark’s story, Luke omits the story of the dancing and decapitation. He merely confirms that John the Baptist rebuked Herod Antipas because of Herodias but merely says that Herod imprisoned John.

Scholars of the New Testament have spent considerable time comparing the accounts in Mark and Matthew with that of Josephus, generally to the discredit of the gospels. Setting questions of historicity aside, the story — in addition to its simple dramatic effect — serves to foreshadow Pilate’s treatment of Jesus, in which a hesitant ruler consigns an innocent prisoner to his death.

As Christians began to seek bones and other relics of martyrs and saints, one relic generated unusual interest and legends. Mark and Matthew report that John’s disciples buried his body, but what did Herodias do with the head? Christians developed a tradition that Joanna, wife of Herod’s steward according to Luke, put it in a jar or vessel of some sort and buried it on the Mount of Olives. However, the burial was just the starting point for many journeys.

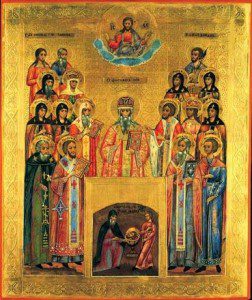

Orthodox Christians commemorate the “first and second finding of the Honorable Head of the Holy Glorious Prophet” on Feb. 24. Here is the narrative from the Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America:

The first finding came to pass during the middle years of the fourth century, through a revelation of the holy Forerunner to two monks, who came to Jerusalem to worship our Saviour’s Tomb. One of them took the venerable head in a clay jar to Emesa in Syria. After his death it went from the hands of one person to another, until it came into the possession of a certain priest-monk named Eustathius, an Arian. Because he ascribed to his own false belief the miracles wrought through the relic of the holy Baptist, he was driven from the cave in which he dwelt, and by dispensation forsook the holy head, which was again made known through a revelation of Saint John, and was found in a water jar, about the year 430, in the days of the Emperor Theodosius the Younger, when Uranius was Bishop of Emesa.

The story continues with the translation (i.e., moving) of the head to Comana in Cappadocia, where it was once again lost:

Because of the vicissitudes of time, the venerable head of the holy Forerunner was lost for a third time and rediscovered in Comana (or Komana) of Cappadocia through a revelation to ‘a certain priest, but it was found not, as before, in a clay jar, but in a silver vessel, and “in a sacred place.” It was taken from Comana to Constantinople and was met with great solemnity by the Emperor, the Patriarch, and the clergy and people.

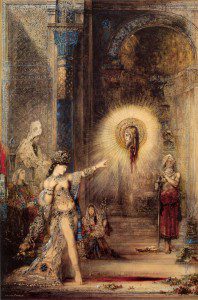

Competing legends abound, as do claims of relics (and, at several churches, entire or partial skulls). As was also the case for the decapitations of Holofernes and Goliath, artists loved the scene. It had violence and sexuality, and banquets make for a lively background. A holy prophet, a lecherous king, and a scheming woman.

Certain biblical stories retain broad cultural currency today: Adam and Eve; Cain and Abel, the Good Samaritan; the Prodigal Son. Others once very well known have become obscure. Judith and the beheading of John the Baptist are both in this category. Even a bit more than a century ago, authors such as Oscar Wilde and Gustave Flaubert made the story of Salome (Christians made the identification via Josephus) and her father famous.

Not every biblical narrative provides a readily digestible spiritual lesson or bright arrow pointing to Jesus Christ. In this case, the foreshadowing of Jesus’s death seems like an appropriate conclusion. But we should also allow scripture to puzzle us, to bother us, and even to entertain us. The Bible contains countless marvelous stories, some of them humorous, some of them grim. The beheading of John the Baptist is one such narrative. Instead of forgetting them, or bothering ourselves unduly about the details of their historicity, we should regard them as the gifts to the church they are and revel in them a bit more.