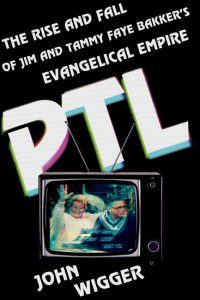

Today I am pleased to welcome John Wigger to The Anxious Bench. John is Professor and Department Chair of History at th e University of Missouri and a former president of the Conference on Faith and History. An American religious and cultural historian, John’s new book PTL: The Rise and Fall of Jim and Tammy Faye Bakker’s Evangelical Empire is forthcoming with Oxford UP.

e University of Missouri and a former president of the Conference on Faith and History. An American religious and cultural historian, John’s new book PTL: The Rise and Fall of Jim and Tammy Faye Bakker’s Evangelical Empire is forthcoming with Oxford UP.

1980s televangelist Jim Bakker is back in the news for his support of Donald Trump. Bakker claims that his backing was key to Trump’s election and in August televangelist Paula White, who has appeared next to Trump at the White House, is scheduled to appear on Bakker’s new television show. But Bakker’s political turn is relatively recent. In the days leading up to the 1980 presidential election, when Bakker was in the process of becoming a television star, he flew on Air Force One with President Carter, visited the White House, and taped an interview with Ronald Reagan, but declined to endorse either candidate. Even now, Bakker’s lack of political grounding is abundantly obvious.

Bakker’s connection with Trump has less to do with politics than with both men’s ability to spot cultural trends and identify what their audiences care about most. Both are entrepreneurs, developers, entertainers, and survivors, with staggering records of accomplishments, failures and comebacks. Both made it big in the 1980s, neither in politics. Indeed, until relatively recently neither showed much interest in politics at all. What has always been more important for Bakker, and it would seem to be the same for Trump in his more recent ventures, is the ability to connect with an audience that more mainstream observers have ign ored, to define a message that many regard as fringe, but that nevertheless appeals to millions.

ored, to define a message that many regard as fringe, but that nevertheless appeals to millions.

Jim and Tammy Bakker made it big in the 1970s and 1980s through innovation. They dropped out of Bible College to get married in 1961 and hit the road as traveling Pentecostal healing evangelists. In 1965 they joined Pat Robertson’s struggling, tiny UHF television station in Portsmouth, Virginia, hired to start a kids show based on a puppet act that was part of their ministry (Tammy was brilliant with those puppets). Bakker’s first breakthrough innovation was the Christian talk show, modeled after the Tonight Show with Johnny Carson, which Bakker and Robertson called the 700 Club. Before that, most Christian television looked like just another church service, while the Tonight Show was the height of cultural cool. As Bakker later told it, he and Tammy would unwind after revival meetings by watching Carson in the trailer they pulled behind their car and wonder why Christians could not do something just as good.

In 1974 Jim and Tammy started the PTL (Praise the Lord or People That Love) network in Charlotte, North Carolina, originally broadcasting out of a former furniture store with half a dozen employees and some makeshift television equipment. PTL’s second innovation under Bakker was the satellite network, launched in 1978, a year before ESPN. PTL got into satellite at just the right time. While the three major networks, CBS, NBC, and ABC, hesitated to commit to the new technology, PTL jumped at the opportunity. As with most innovations, those who got in first had a significant advantage. With satellite, PTL was there from the start.

The satellite network beamed Christian programming into millions of homes twenty-four hours a day, allowing PTL to create its own programming and sell airtime to other ministries. Jim and Tammy’s signature program, originally called the PTL Club, featured two hours of live, unscripted television a day in front of a studio audience, five days a week. What the show lacked in polish, it made up for in spontaneity and unfiltered candor, particularly from Tammy. It was a sort of reality TV before the term was invented. For millions, PTL was more relevant than their local church and Jim and Tammy became part of their extended family. The ministry’s programming was eventually available in forty nations.

The enormous fundraising potential of the satellite network enabled Bakker to initiate a third innovation, creating a Christian Disneyland on the North and South Carolina border. Heritage USA was unlike anything else in America, with a $13 million waterpark and a wide range of lodging and activities, morning to midnight. In 1986 six million people visited Heritage USA and the ministry had revenues of $129 million.

By then the Bakker’s had become proponents of the prosperity gospel, a message that fit the 1980s perfectly. “God wants you to be happy, God wants you to be rich, God wants you to prosper,” Bakker wrote in Eight Keys to Success, published in 1980. Jim and Tammy practiced what they preached. They used PTL money to buy a 10,000-square-foot home near their headquarters in North Carolina, a condo on the Florida coast, and vacation homes in Palm Springs, Palm Desert, and Gatlinburg, Tennessee. They traveled with an entourage, flew first class or chartered jets, bought luxury cars, boats, and expensive clothes, and showed it all off for the world to see. On one occasion, in June 1984, Bakker chartered a Learjet to fly the ninety-three miles from Palm Springs to Santa Ana, California, so that he could buy two vintage Rolls Royces, a 1953 Silver Dawn and a 1939 Phantom III. The next day, back at their vacation home in Palm Desert, Jim, feeling a little sheepish after spending so much on himself, bought Tammy Faye a new Mercedes. They had everything, all the time.

Then it all came crashing down.

On March 19, 1987 Jim Bakker resigned in disgrace from PTL after his December 1980 sexual encounter with Jessica Hahn in a Florida hotel room became public. Hahn told her story to Playboy, accusing Bakker of what amounted to rape, while Bakker claimed that she was a professional who knew “all the tricks of the trade.” In the wake of the Hahn revelation, stories surfaced about Bakker’s involvement in gay relationships and visits to prostitutes, sometimes wearing a blond wig as a disguise.

The scandal was initially about sex, but it soon turned to money, after it was discovered that PTL had paid Hahn and her representatives $265,000 in hush money. When he resigned, Bakker turned the ministry over to fundamentalist preacher Jerry Falwell. He and his team quickly discovered that PTL was $65 million in debt and bleeding money at a rate of $2 million a month. Millions had been illegally syphoned off by senior employees. The ministry filed for bankruptcy that year.

Two years later, in 1989, Bakker went on trial for wire and mail fraud. The trial unfolded in a circus-like atmosphere before US District Judge Robert “Maximum Bob” Potter. A witness collapsed on the stand and Bakker had a psychological breakdown, crawling under his lawyer’s couch as federal marshals came to get him. He was convicted and sentenced to forty-five years in prison, serving nearly five years before his release.

For the Bakkers, the prosperity gospel was more a product of their success than a cause. After the fall, Tammy became an icon in the gay community, the Judy Garland of televangelism. Jim’s new television ministry, located appropriately enough just outside Branson, Missouri, is centered on selling survivalist food and gear to preppers, along with backing right-wing political causes. What Trump and Bakker have in common is not so much politics or even religion, but a desire to be at the center of the next big thing, to find out what people want most and then fashion a message that answers those concerns. In Bakker’s case this goes a long way toward explaining how deep religious devotion can become so entwined with money, sex, and celebrity on a Hollywood scale. It’s a story that transcends politics alone, connecting to a much wider range of human motivations.