We’re gearing up to start another academic year at Bethel University, where one of my favorite courses is a first-year general education offering called Christianity and Western Culture, or CWC. A one-semester historical sprint from ancient Greece through the Enlightenment that folds in philosophy, theology, and a bit of political science and art history, CWC is taken by something like 70% of students at Bethel. (The rest fulfill the requirement as part of a multi-semester Great Books program.) While I’ve got my reservations about “Western civ,” CWC is a great opportunity to make the case for the value of history to a cross-section of young evangelical Christians, and to help them ask of themselves the course’s timeless recurring questions: Who am I, and who should I be? Who I am in relation to others? How do Christians relate to culture? And how do I answer these questions?

But as valuable as it is for students, I know that teaching CWC for fifteen years has also done wonders for my own intellectual and spiritual development. Among other benefits, it’s helped fill in some of the significant holes in my own knowledge of the Christian story — at least in part of the world. For example, as I edited our primary source reading packet last week, I realized that CWC has introduced me to several important women whose stories fell through the cracks of my undergraduate or graduate education, to say nothing of the little I’d learned of church history in church itself.

Gender is an increasingly important theme in a course whose narrative starts with Sophocles’ character Antigone insisting that nothing the misogynistic tyrant Creon “proclaimed strong enough to let a mortal override the gods and their unwritten and unchanging laws” and ends with Mary Wollstonecraft vindicating women’s rights: “Would men but generously snap our chains, and be content with rational fellowship, instead of slavish obedience, they would find us more observant daughters, more affectionate sisters, more faithful wives, more reasonable mothers—in a word, better citizens.” To end the course this year, we’re dedicating a closing week and final essay to the experience of women in the modern age.

So let me introduce you to seven women in the great cloud of witnesses I’ll reflect on when CWC opens on Monday morning. It’s not an exhaustive list. (For example, I left out the poet Christine de Pizan, a favorite figure from my Late Middle Ages lecture, since Beth introduced her earlier this year.) But it is an inspiring one.

Perpetua and Felicitas (d. 203)

To introduce students the Roman persecution of Christians, we have them read a unique martyrdom account, attributed to a young North African woman named Perpetua, who died in Carthage alongside a slave named Felicitas (who gave birth to her daughter while in prison) and other companions. If truly written by Perpetua, it’s a rare extant source authored by an early Christian woman. In any event, it’s a powerful account of faithfulness, as Perpetua stands up not only to the local imperial magistrate, but to her imperious father. The patriarchy of the West — and of Western Christianity — silences the vast majority of women from the era we cover, so it’s especially powerful to hear the voice of a young woman telling a man with enormous power over her that she “cannot be called anything else, except what I am, a Christian.” (A statement that she says enraged him to the point of wanting “to tear out my eyes.”)

Learn more: Two fine articles in Christian History Magazine put Perpetua in a larger context: Elesha Coffman’s “Faith of Our Mothers” (which surveys the role of women in the Early Church) and Edwin Woodruff Tait’s “The Hunger Games and the Love Feast.”

Hildegard of Bingen (1098-1179)

A Benedictine abbess, writer, and composer, Hildegard has been much in the news in recent years. In 2009 she was the subject of a movie by the great German director Margarethe von Trotta.

Then three years later, Pope Benedict XVI named her a Doctor of the Church, just the fourth woman to join a list dominated by male theologians like Augustine and Thomas Aquinas. (Another such Doctor also appears in our reading packet: the 16th century Catholic reformer Teresa of Ávila.) “This great woman,” wrote Benedict of his fellow German, “truly stands out crystal clear against the horizon of history for her holiness of life and the originality of her teaching. And, as with every authentic human and theological experience, her authority reaches far beyond the confines of a single epoch or society; despite the distance of time and culture, her thought has proven to be of lasting relevance.”

We include Hildegard primarily to help students understand the importance of mysticism in medieval Christianity, as they read her account of ecstatic visions that “inflamed my whole heart and my whole breast, not like a burning but like a warming flame, as the sun warms anything its rays touch.” But she also illustrates how monasticism created space for women not only to hold positions of leadership, but to exert wider influence in medieval society. “Beware,” one of her most famous letters warned Emperor Frederick Barbarossa during one of his conflicts with Rome, “that the almighty King does not lay you low because of the blindness of your eyes, which fail to see correctly how to hold the rod of proper governance in your hand. See to it that you do not act in such a way that you lose the grace of God.”

Learn more: There are many studies of Hildegard. From a Benedictine publishing house up the freeway from Bethel, pick up a copy of Anne King-Lenzmeier, Hildegard of Bingen: An Integrated Vision.

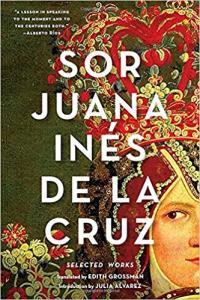

Sor Juana Inés (1651-1695) and Johanna Eleonora Petersen (1644-1724)

Two more recent additions to our reader come from 17th century Europe, where Juana Inés de la Cruz and Johanna Eleonora Petersen occupied opposing sides of the religious divide left over from the Reformation. An incredibly well-read Spanish nun of the 17th century, Sor Juana raised the hackles of her local bishop, who insisted that she sell her library. “God has favored me with a great love of the truth,” she replied, “ever since the first light of reason struck me, my inclination toward letters has been so strong and powerful that neither the reprimands of others – I have had many – nor my own reflections – I have engaged in more than a few – have sufficed to make me abandon this natural impulse that God placed in me.” Like Christine de Pizan, she appealed to biblical and historical examples of God working through women of faith.

Two more recent additions to our reader come from 17th century Europe, where Juana Inés de la Cruz and Johanna Eleonora Petersen occupied opposing sides of the religious divide left over from the Reformation. An incredibly well-read Spanish nun of the 17th century, Sor Juana raised the hackles of her local bishop, who insisted that she sell her library. “God has favored me with a great love of the truth,” she replied, “ever since the first light of reason struck me, my inclination toward letters has been so strong and powerful that neither the reprimands of others – I have had many – nor my own reflections – I have engaged in more than a few – have sufficed to make me abandon this natural impulse that God placed in me.” Like Christine de Pizan, she appealed to biblical and historical examples of God working through women of faith.

Then from my own religious tradition, we include Petersen alongside Philipp Jakob Spener as leaders of German Pietism. The founder of a conventicle that eventually became too radical in theology for Spener and other “churchly” Pietists, Petersen wrote some fifteen books, taught Bible and Greek to young girls, and even preached on occasion. “Some may be doubtful that this kind of writing should be produced by me since I am a woman,” she acknowledged in a 1696 commentary on Revelation. “But I also know that in Christ Jesus, in the distribution of grace and the Spirit, there is neither male nor female, Galatians 3:28, and that the grace and gift of God must not be quenched or suppressed. So while I know how to govern myself with proper submission in the Church of God, I also know that I must not hide the gift I received from God under a bushel [Matt 5:15] but use it to His honor and to the benefit of my neighbor.”

Learn more: Petersen’s spiritual autobiography has been translated into English by Barbara Becker-Cantarino, and Norton recently published Edith Grossman’s translation of some of Sor Juana’s works.

Sarah Grimké (1792-1893) and Sojourner Truth (1797-1883)

Bethel’s curriculum limits CWC’s responsibility to the period ending in 1800, but we always conclude by nudging into 19th century American history. This year, students will read from two abolitionists of deep Christian faith. Raised on a plantation in South Carolina, Sarah Moore Grimké became a Quaker after moving north, and was influenced by the anti-slavery writings of John Woolman. “That such a state of society should exist in a Christian nation,” Grimké wrote to the Boston abolitionist Mary Parker in 1838, “claiming to be the most enlightened upon earth, without calling forth any particular attention to its existence, though ever before our eyes and in our families, is a moral phenomenon at once unaccountable and disgraceful.”

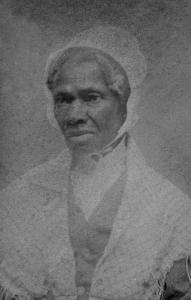

Born into slavery as the property of a Dutch-speaking family in New York, Sojourner Truth won her freedom and changed her name after becoming a Methodist in 1843. Despite playing a key role in winning the emancipation of enslaved African Americans, Truth lamented in 1867 that

There is a great stir about colored men getting their rights, but not a word about the colored women; and if colored men get their rights, and not colored women theirs, you see the colored men will be masters over the women, and it will be just as bad as it was before. So I am for keeping the thing going while things are stirring; because if we wait till it is still, it will take a great while to get it going again.

Learn more: On the intersection of women’s rights and the abolitionist movement, see Beth Salerno’s Sister Societies and Anna Speicher’s The Religious World of Antislavery Women.