Nicholas Pruitt teaches in the Department of History at Eastern Nazarene College. He’s also a newly minted Ph.D. from Baylor University. Last month, I heard Nick give a talk at the American Society of Church History. At the time, I was feeling rather depressed about the fact that throughout the course of American history, native-born Protestants frequently have embraced anti-immigrant positions. Nick’s talk raised my spirits, because he discussed the fact that many mainline Protestants in the first half of the twentieth century went to great lengths to oppose racism and welcome immigrants. Here is a guest post from Nick that discusses some of that history.

St. Augustine articulated in the City of God the idea that fifth-century Christians were citizens of both heaven and earth, and this distinction has served as a fit description of Christian loyalties ever since. This dual-citizenship has never remained static as each generation and community of believers reinterprets their spiritual and earthly commitments, and Christians have never separated these loyalties entirely. It should come as no surprise then that the topic of immigration, ever since the rise of nation-states, has brought front and center Christianity’s relationship to church and state. As citizens of the Kingdom of God, should Christians offer compassion and aid to the “stranger,” or are immigrants “foreigners” who pose a national challenge?

St. Augustine articulated in the City of God the idea that fifth-century Christians were citizens of both heaven and earth, and this distinction has served as a fit description of Christian loyalties ever since. This dual-citizenship has never remained static as each generation and community of believers reinterprets their spiritual and earthly commitments, and Christians have never separated these loyalties entirely. It should come as no surprise then that the topic of immigration, ever since the rise of nation-states, has brought front and center Christianity’s relationship to church and state. As citizens of the Kingdom of God, should Christians offer compassion and aid to the “stranger,” or are immigrants “foreigners” who pose a national challenge?

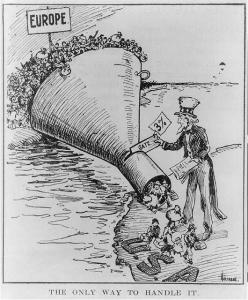

The policy and rhetoric of the current U.S. administration has enflamed public discourse on immigration over the last year, as immigrants and refugees of various nationalities and ages have become pawns in the hands of politicians. In the midst of these current debates, Christians are searching for answers. Historians point out that restriction and anti-immigrant views are nothing new to America, and that white Protestants acted upon nativist convictions during the nineteenth century as they encountered immigrants who arrived having brought their Catholic faith with them. (I’m currently typing just ten miles from the site where certain Massachusetts residents in 1834 burned a Catholic convent to the ground on account of nativist, anti-Catholic suspicions.) This narrative usually concludes with the legislation passed in 1924 that implemented immigrant quotas that greatly reduced immigration from eastern and southern Europe and excluded Japanese entirely.

As a graduate student studying American history, I chose to write my dissertation on the ways that white Protestants responded to U.S. immigration policy and ethnic communities after 1924, ending my research with the 1965 legislation signed by Lyndon B. Johnson that overturned previous restriction. What I discovered is a history of varied responses that offers manifold options for twenty-first century Christians grappling with the charged political debates and grave needs of immigrants and refugees. Understanding how earlier generations came to terms with these issues will go a long way in helping today’s church respond.

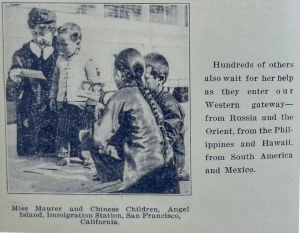

You can pick nearly any component of the current immigration debate and find precedents in twentieth century American history. Wondering how to relate to the discussion over Dreamers and undocumented immigrants? Turn to the Kerr-Coolidge Bill considered in 1936, which the Federal Council of Churches believed would “humanize our immigration laws, and especially avoid unnecessary breaking up of families of immigrants of good character.” Considering ministering to local immigrants in your community? You will find tomes of material on denominational home mission efforts throughout the century to assist, “Americanize,” and share the Gospel with the “foreigner.” Concerned about how to approach the Syrian refugee crisis? Ample precedent can be found in resettlement efforts sponsored by multiple Protestant denominations after World War II and during the Cold War. Such initiatives aided mostly Protestant refugees fleeing war-torn Europe, but there were some instances when American Protestants helped resettle Catholic, Jewish, Orthodox, and even Muslim refugees. While these examples are fairly progressive, they must not, however, be considered the full story. Many Protestants still continued to grapple with national concerns and what consequences immigrants and refugees might pose for American culture. One Methodist bishop purportedly announced in 1926, “I am one hundred per cent Anglo-Saxon. America is a Protestant nation and always will remain so. . . . We never will surrender our priceless American heritage to the hands of the foreigners who trample on our flag.”

You can pick nearly any component of the current immigration debate and find precedents in twentieth century American history. Wondering how to relate to the discussion over Dreamers and undocumented immigrants? Turn to the Kerr-Coolidge Bill considered in 1936, which the Federal Council of Churches believed would “humanize our immigration laws, and especially avoid unnecessary breaking up of families of immigrants of good character.” Considering ministering to local immigrants in your community? You will find tomes of material on denominational home mission efforts throughout the century to assist, “Americanize,” and share the Gospel with the “foreigner.” Concerned about how to approach the Syrian refugee crisis? Ample precedent can be found in resettlement efforts sponsored by multiple Protestant denominations after World War II and during the Cold War. Such initiatives aided mostly Protestant refugees fleeing war-torn Europe, but there were some instances when American Protestants helped resettle Catholic, Jewish, Orthodox, and even Muslim refugees. While these examples are fairly progressive, they must not, however, be considered the full story. Many Protestants still continued to grapple with national concerns and what consequences immigrants and refugees might pose for American culture. One Methodist bishop purportedly announced in 1926, “I am one hundred per cent Anglo-Saxon. America is a Protestant nation and always will remain so. . . . We never will surrender our priceless American heritage to the hands of the foreigners who trample on our flag.”

To demonstrate the complexity, and yet opportunity, embedded in such history, I turn to a case study – the Protestant response to the Immigration Act of 1924. This legislation, a revision of policy already put in place in 1921, enforced restrictive quotas that, while reducing overall immigration, still favored northern Europeans who had already settled in the United States before 1890.  These groups, such as the British, Irish, Germans, and Scandinavians, either spoke English or were often practicing Protestants. Most historians point out that culturally dominant Protestants embraced the legislation as an attempt to curb annual immigration and preserve a national identity premised on Anglo-Saxon ideals. While this assessment gets much right, the history is not that simple. Many Protestant leaders found the 1924 law less than satisfactory. At issue for some Christians was the legislation’s exclusion of Japanese immigrants. Religious critics noted the challenges such a policy would create for foreign missions in Japan. Others turned to a more theological basis and argued that it discredited the notion of the “brotherhood of man,” a principle in vogue among social gospel thinkers at the turn of the century that stressed a common humanity before God, regardless of race or creed. Drawing from this ideal, some religious figures then challenged the law because of the injustice and discrimination it committed in singling out Japanese immigrants (in addition to Chinese exclusion already in place since 1882). Even Southern Baptists, often reticent to broach political matters through denominational channels, criticized the legislation on the basis that it perpetuated the “inhuman treatment, and injustice inflicted upon an innocent people.” Several ecumenical leaders also had grave concerns over whether such a policy would upset a delicate international order just six years after World War I and at a time when Japan was aggressively expanding its control over East Asia.

These groups, such as the British, Irish, Germans, and Scandinavians, either spoke English or were often practicing Protestants. Most historians point out that culturally dominant Protestants embraced the legislation as an attempt to curb annual immigration and preserve a national identity premised on Anglo-Saxon ideals. While this assessment gets much right, the history is not that simple. Many Protestant leaders found the 1924 law less than satisfactory. At issue for some Christians was the legislation’s exclusion of Japanese immigrants. Religious critics noted the challenges such a policy would create for foreign missions in Japan. Others turned to a more theological basis and argued that it discredited the notion of the “brotherhood of man,” a principle in vogue among social gospel thinkers at the turn of the century that stressed a common humanity before God, regardless of race or creed. Drawing from this ideal, some religious figures then challenged the law because of the injustice and discrimination it committed in singling out Japanese immigrants (in addition to Chinese exclusion already in place since 1882). Even Southern Baptists, often reticent to broach political matters through denominational channels, criticized the legislation on the basis that it perpetuated the “inhuman treatment, and injustice inflicted upon an innocent people.” Several ecumenical leaders also had grave concerns over whether such a policy would upset a delicate international order just six years after World War I and at a time when Japan was aggressively expanding its control over East Asia.

What is demonstrably absent, however, in these critical appraisals of the Immigration Act of 1924 is that the law also discriminated against people from southern and eastern Europe. While their concerns over Japanese exclusion represented a more prophetic position amidst strong anti-Asian, nativist currents, many Protestants still accepted the common argument that Catholic and Jewish immigrants streaming in at unprecedented rates from Italy and eastern Europe threatened American culture and society. As did most other Americans at the time, Protestants had little faith in America’s ability to absorb so many immigrants who spoke different languages, practiced other faiths, and were often poor. Many Christians who opposed Asian exclusion simply wanted to apply the same restrictive quotas to Japanese and Chinese immigrants. While the outright exclusion of certain nationalities was unjust, immigration still posed a national threat that called for restriction.

Many Protestants in the United States today remain apprehensive over immigration and the diversity it brings. There is a perpetual fear that the nation’s identity is under siege and the “American way of life” must be protected. Over the course of the nation’s history, American Protestants have often reflected broader cultural trends as they cycled through episodes of fear over the immigration of Catholics, anarchists, socialists, communists, and more recently Muslims. The Christian church has much to offer current discussions and debates over immigration. As members of a global community of believers both multiracial and multicultural, Christians are capable of offering valuable insight. But as American Christians address the needs of immigrants and refugees and consider policy proposals, they must also critically assess their relationship to culture at large. Are they a greater reflection of an earthly kingdom, or the Kingdom of God? In so doing, they must not forget that beyond policy debates and bickering TV pundits are immigrants and refugees needing assistance as they look for opportunities and flee circumstances unimaginable to most Americans.