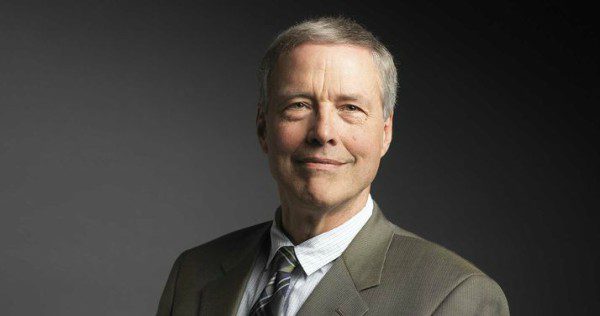

As prominent evangelical leaders gather this week at Wheaton, IL, to discuss how the Trump era “has unleashed [a] ‘grotesque caricature’ of their faith,” historian James Bratt of Calvin College joins us today at the Anxious Bench to weigh in with some thoughts on Christianity and Evangelicalism, and the death (and resurrection) of a movement.

I recently attended a conference at Notre Dame honoring the career of Mark Noll. As one of the most accomplished scholars of American religious history, as well as a person of deep faith, consummate integrity, and easy humor—and genuine humility to top it off—Mark is more than worthy of honor, and the participants made sure he received it, with remarks that were by turn analytic, humorous, and touching. Mark being Mark, however, the program was full of robust scholarship and featured rising younger scholars as well as the old lions.

The panelists attended to American religious history in its various eras as well as in the comparative global perspective at which Mark has been a notable pioneer. Things got most interesting for me in the concluding panel, which riffed off of what is probably Mark’s most famous book, The Scandal of the Evangelical Mind (1994). The scandal, Mark famously opined back then, was that there wasn’t much of one—an evangelical mind, that is. The panelists weighed in on the extent

to which that situation has since been corrected, but in the process veered off into attempts to define just what is, and what is not, “evangelical.”

To me that inevitable but tiresome digression cost an opportunity to think about what might be the bombshell book equivalent to Mark’s Scandal for our own moment. I’d pick addressing the elephant in the room and asking—in the face of consistent polling that shows white “evangelicals” to be supporting Donald Trump at just about the 80% mark by which they favored him in the 2016 presidential election—what future evangelicalism has in the United States. And, more broadly yet fundamentally, what sort of religion white “evangelicalism” might be.

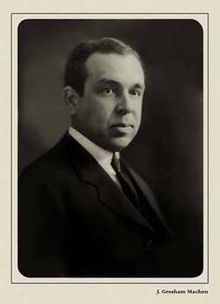

A number of the younger panelists raised this concern during the conference, and a host of commentators religious and secular have bruited the matter ever since Trump descended his hotel’s golden escalator onto the American political scene three years ago. My historian’s input is to suggest that we not just consult current opinion polls or attend to the evangelical leaders who have either advanced or decried the brand’s association with the man. Instead, let’s return to a foundational text from the evangelical past—indeed, the text which helped define the present-day movement’s Fundamentalist parent in the eyes of its devotees and outside observers alike. I mean J. Gresham Machen’s Christianity and Liberalism (1923).

In that book Machen argued that the “orthodox” and “liberal” parties then warring for the future of American Protestantism were not, as the second party claimed, carrying on a family feud within the big tent of Christianity. Rather, he insisted, they represented two entirely different religions. The orthodox side held to the historic, apostolic faith; the liberals were parading a combination of philosophical naturalism and sentimental humanitarianism behind the garments of Christian terminology. Their pose was dishonest and dishonorable, Machen continued, and the sooner they dropped it, the better for all concerned. At least then the real issues could be discussed more intelligently and profitably.

So, my modest proposal. Let the next bombshell book on the subject take a hint from Machen and be entitled Christianity and Evangelicalism. Its author could be more charitable than Machen (one could hardly be less) and treat white evangelicalism as not a totally different religion contrary to Christianity but as a deeply corrupted version of the faith whose name it claims. A totally depraved version, my Calvinist theology would put it: that is, tainted in every part and as a whole and unable to cleanse itself by its own power, but requiring a supernatural redemption via a miraculous intervention, registering as a conversion. That depravity, in turn, opens the question of whence it arose, of what might be the original sin in which it is rooted. Is it misogyny, racism, militarism, imperialism, materialism, xenophobia, collective narcissism, arrogant entitlement, abject fear, self-righteousness, sacred nationalism? Or something deeper yet that unites all of the above? Certainly, these traits are manifest, proudly and without apology, in the Trumpian White House and policy initiatives. And just as certainly, the 80% of white evangelicals who hold fast to Donald Trump have signed on to them with little—well, sometimes, just a little—embarrassment. Just as certainly still, the list and the behavior of the figurehead who embodies them, are all far, very far, from the kingdom of heaven. The results are toxic to the evangelical brand in particular and to the prospects of religion in public life in general.

Yet the picture is more mixed than this. To repeat, evangelicalism counts as a profoundly corrupted Christianity but not simply, or not yet, a non- or anti-Christian religion as Machen characterized Protestant liberalism a century ago. White evangelicals can point to Jesus’ criteria (in Matthew 25) for deciding who are the sheep and who are the goats at the final assay and say that they do indeed attend to the sick, feed the hungry, visit the prisoner, etc. The contradiction, of course, is that these efforts via voluntary charities rub up against public policies that would abandon the sick, depriv

e the hungry of food, and throw more and more people—people of color especially—into prison. The current situation thus exposes more clearly than ever the fateful political ideology that white evangelicals have come more and more to follow over the 20th century. They have followed now it to the point of paying allegiance, seemingly unbreakable allegiance, to the most egregious goat ever to occupy the Oval Office.

The first task of Christianity and Evangelicalism would thus be to explain how and why the latter has come to be a noxious version of the former. A lot of the empirical work toward that end has been done. I suggest adding some historical comparison by way of another classic text, Will Herberg’s Protestant, Catholic, Jew (1955). Besides appearing about halfway between Machen’s book and Noll’s, its analytic frame and treasury of polling data show a socio-cultural corruption of Christianity in the 1950s’ supposedly halcyon days of a great and pious America, only this time among Catholics and the Protestant “mainline” too. How else could a near majority of self-identified “Christians” not be able to name one of the four gospels? How else—this is my particular favorite—could American Christians, when asked to rate the most important event in world history, put Jesus’ life, death, and resurrection in a tie for fourteenth place alongside the invention of the x-ray and the Wright brothers’ flight at Kitty Hawk? Herberg, Jewish himself, was profoundly worried about this gap between professed and operative religion. We are no less, and can find in his portrait of the idols of the tribe that stood between the two some clear culprits explaining the great gap of our day.

The second, and harder, task of Christianity and Evangelicalism, would be to suggest some steps by which the latter could become Christian again. Here, ironically, the attempt by some evangelicals to sanctify Donald Trump might work well if given a quarter turn: he is no Cyrus, a pagan ordained of God to restore Jews to Israel, but Nebuchadnezzar, the pagan invader of Israel ordained of God to punish them for their unfaithfulness, and banishing the best of them from the promised land in the bargain. As intriguing might be the possibility of seeing that pagan’s later fate play out again—that is, to see the proud trumpet of egotistical greatness reduced to crawling around like a beast in the field, eating grass and growing literal instead of just figurative claws (Daniel 4)—one’s relish at the prospect bespeaks an unsanctified longing of its own.

The better role might be to follow after a truly scandalous prophet, Ezekiel; to describe and survey the scattered dry bones of a once favored people; and to ask by what means they might possibly live again. No mistake: this option entails death, exile, and damnation. Perhaps we’re left just there, right with the founder of Christianity. Perhaps this, and only this, is the path to resurrection and redemption.