Let me put the past to the side for a week and think instead of the future. Imagine that it’s the year 2118, and evangelicalism is a thriving religious movement.

However unlikely it may seem to you now, imagine that evangelicalism in one hundred years is doing as well as it ever has, by whatever quantitative or qualitative measure you prefer. Now, imagine that some future historian — perhaps some future Anxious Bench blogger — is looking back a century to the Trump era, trying to figure out what happened: How, she asks herself, did evangelicalism experience revival, rather than succumbing to the crisis that so many of its observers and participants described in 2018?

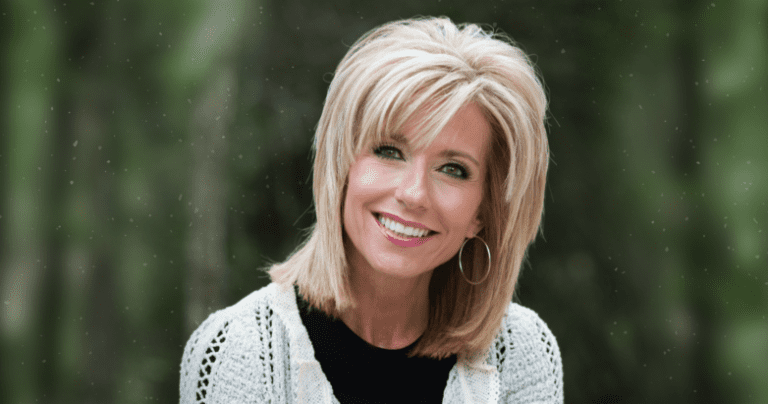

I imagine my early 22nd century counterpart poring over digital archives when she stumbles across a blog post dated May 3, 2018. She perks up as she reads words written by a woman named Beth Moore, as an open “Letter to My Brothers”:

I came face to face with one of the most demoralizing realizations of my adult life: Scripture was not the reason for the colossal disregard and disrespect of women among many of these men. It was only the excuse. Sin was the reason. Ungodliness.

This is where I cry foul and not for my own sake. Most of my life is behind me. I do so for sake of my gender, for the sake of our sisters in Christ and for the sake of other female leaders who will be faced with similar challenges. I do so for the sake of my brothers because Christlikeness is at stake and many of you are in positions to foster Christlikeness in your sons and in the men under your influence. The dignity with which Christ treated women in the Gospels is fiercely beautiful and it was not conditional upon their understanding their place.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pF1yI194s6E

I don’t think I paid Beth Moore anything like the attention she deserved until October 2016, when she featured prominently in Kate Bowler’s address to the Conference on Faith and History — on “women in megaministry” who had achieved significant influence despite serving in conservative Protestant contexts that expected women not to preach or teach men.

https://twitter.com/cgehrz/status/789835194043883520

In her open letter, Moore related some of her challenges in pursuing this kind of ministry in an evangelical and Southern Baptist context: learning to show “constant pronounced deference” to men… weathering insults and charges of heresy from men… her disillusioning encounter with a respected male theologian who “looked me up and down, smiled approvingly and said, ‘You are better looking than __________.’ He didn’t leave it blank. He filled it in with the name of another woman Bible teacher.” Through it all, Moore “accepted the peculiarities accompanying female leadership in a conservative Christian world, because I chose to believe that, whether or not some of the actions and attitudes seemed godly to me, they were rooted in deep convictions based on passages from 1 Timothy 2 and 1 Corinthians 14.”

But in the same month as Bowler’s plenary address, Moore says that she experienced her realization that it was sin, not Scripture, that accounted for such treatment of women. In October 2016, she recalls in last week’s open letter, there “surfaced attitudes among some key Christian leaders that smacked of misogyny, objectification and astonishing disesteem of women and it spread like wildfire. It was just the beginning.”

She doesn’t specify just what happened, but I suspect that she has in mind the response of some male evangelical leaders to the Access Hollywood tapes. Even after Donald Trump was caught bragging about sexually abusing women, prominent evangelicals like Franklin Graham, Robert Jeffress, and Tony Perkins refused to back off their support for the Republican candidate. (Also urging votes for Trump that fall was another man lurking in the background of Moore’s letter: Paige Patterson, the embattled president of Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary.)

A few weeks later, Buzzfeed ran a profile of several of the women from Bowler’s talk. Reporter Anne Helen Peterson noted that “[s]everal of the most visible and influential of these New Christian Women… have openly criticized Trump…. And they’ve watched, in dismay, as male leaders have continued to endorse him.” Having already suggested earlier in the fall that evangelical leadership should look more like the demographics of a movement that is 55% female, I now wrote at my blog that “to a certain extent, that change in leadership is already happening — until now, mostly beyond the notice of evangelical men like me.”

That was November 7, 2016.

The following day, Donald Trump pulled out a narrow victory over Hillary Clinton, thanks in no small part to the support of over 80% of those white evangelicals who voted.

So I’ve been especially interested to see how these evangelical women would respond to the Age of Trump. Like Beth (Barr), I was fascinated to see (Beth) Moore’s Twitter thread this past March, when she repented “of ways I’ve been complicit in & contributed to misogyny & sexism in the church by my cowardly and inordinate deference to male leaders in order to survive rather than simply, appropriately respecting them as my brothers.” (And then “of being complicit in & contributing to racism & white supremacy in the church by profiting off a system that was unjust to people of color” — but that’s another post.)

Now, Moore’s open letter doesn’t mention Donald Trump, who certainly seems like the epicenter of the earthquake threatening the present witness and future viability of evangelicalism. Unlike conservative commentator David French, who wrote his own open letter on the same day, she didn’t call out fellow evangelicals who continue to support Trump despite gathering evidence of his misogyny, infidelity, and dishonesty. “I’m sorry,” wrote French, “but you cannot compartmentalize this behavior, declare that it’s ‘just politics,’ and take solace that you’re a good spouse or parent, that you serve in your church and volunteer for mission trips, or that you’re relatively charitable and kind in other contexts. It’s sin, and it’s sin that is collapsing the Evangelical moral witness.”

Moore addressed none of this, directly. Yet her open letter is vastly more important than French’s: both in its own right and as it may embolden other women to speak in the months and years to come.

It’s not that French was wrong. He’s absolutely right to warn that “there are now millions — millions — of our fellow citizens who despise us not because we follow Christ (the kind of persecution we expect) but because all too many fellow believers have torched their credibility and exposed immense hypocrisy through fear, faithlessness, and ambition.” But I don’t think that his open letter can change those evangelical hearts and minds that had long since been conditioned to accept female deference to a certain kind of male authority. As Kristin wrote for Religion & Politics in January 2017,

white evangelical support for Trump can be seen as the culmination of a decades-long embrace of militant masculinity, a masculinity that has enshrined patriarchal authority, condoned a callous display of power at home and abroad, and functioned as a linchpin in the political and social worldviews of conservative white evangelicals. In the end, many evangelicals did not vote for Trump despite their beliefs, but because of them.

“Soon enough,” concludes French, “the ‘need’ to defend Trump will pass. He’ll be gone from the American scene. Then, you’ll stand in the wreckage of your own reputation and ask yourself, ‘Was it worth it?'” But a true revival of evangelicalism will only happen if evangelicals realize that the wreckage was of their own making, and only partially connected to partisan politics.

For there are countless other ruins already smoldering in churches, seminaries, and families where evangelical men took advantage of their power. Some abused women, or covered up the abuse of women. Others stifled the voices of women, questioned their callings, or ridiculed their aspirations.

Moore admits in her letter that the disrespect and humiliation she endured “may seem fairly benign in light of recent scandals of sexual abuse and assault coming to light but the attitudes are growing from the same dangerously malignant root. Many women have experienced horrific abuses within the power structures of our Christian world. Being any part of shaping misogynistic attitudes, whether or not they result in criminal behaviors, is sinful and harmful and produces terrible fruit.”

So she closes by asking that her brothers in Christ “would simply have no tolerance for misogyny and dismissiveness toward women in your spheres of influence. I’m asking for your deliberate and clearly conveyed influence toward the imitation of Christ in His attitude and actions toward women.”

That’s a good first step — and perhaps one that will cause many evangelical men to rethink their own behavior towards women… and what they’re willing to condone in the conduct and rhetoric of their religious and political leaders.

But Moore also asks that evangelical men recognize “some of the skewed attitudes many of your sisters encounter. Many churches quick to teach submission are often slow to point out that women were also among the followers of Christ (Luke 8), that the first recorded word out of His resurrected mouth was ‘woman’ (John 20:15) and that same woman was the first evangelist.”

Mary Magdalene proceeded to bear witness to the hope of the resurrection — to men who proceeded to lock their doors in fear (John 20:18-19). Again and again throughout church history, women have been called upon to announce good news: often in the midst of sorrow and suffering, to be evangelists.

This time may men have ears to hear voices like Beth Moore’s. For in the end, that’s precisely what evangelicalism needs most: to be evangelized.