Melissa Borja, assistant professor in American Culture at the University of Michigan, returns today to the Anxious Bench.

This week the Supreme Court ruled in a 5-4 decision to uphold President Trump’s travel ban, on the grounds that it was within the President’s power to restrict immigration in the interest of national security. The decision met harsh condemnation and protest. Most notably, Justice Sonia Sotomayor offered a fiery dissent. Beginning by saying that “the United States of America is a nation built upon the promise of religious liberty,” she criticized the Supreme Court’s decision for failing to “safeguard that fundamental principle.” Listing numerous instances in which Mr. Trump had discussed his plans to “create a Muslim registry or ban Muslim immigration,” Justice Sotomayor declared that the travel ban was “motivated by hostility and animus toward the Muslim faith” and was “an exclusionary policy of sweeping proportion” that “was rooted in dangerous stereotypes about, inter alia, a particular group’s supposed inability to assimilate and desire to harm the United States.”

She was not alone in her condemnation of the decision. Farhana Khera of Muslim Advocates decried the Trump administration’s “anti-Muslim agenda” and compared the ruling to slavery, segregation, and Japanese incarceration. The Baptist Joint Committee for Religious Liberty announced that it was “deeply disappointed by the Supreme Court’s refusal to repudiate policy rooted in animus against Muslims.” And in cities across the nation, thousands of protesters took to the street to voice both their anger at the Supreme Court decision and their support of Muslim Americans.

Given the composition of the Supreme Court, the dec ision was perhaps not a surprise, nor was the impassioned response to it. What did seem surprising was the degree to which Americans seemed genuinely shocked by the realization that religious animus thrives in the United States today. Religious animus, it became clear to many people yesterday, is not merely embraced by a few bigoted people, but enacted it our government’s laws and policies. This is a difficult truth for Americans to confront, but an important one. Religious hatred has a long and shameful history in this country. Like racism, religious hatred is in America’s DNA.

Moreover, religious animus has always been a central feature of our nation’s immigration politics. Historians have tended to explain the rise of anti-immigrant movements and the development of restrictionist and exclusionist policies by emphasizing a few common themes—in particular, racial resentment, economic anxiety, and national security. However, the Trump travel ban illuminates the need for religion to be at the center of our understanding of American nativism. Religious animus has been a powerful force behind nativist movements and exclusionist immigration measures throughout American history, and just as we cannot understand anti-immigrant movements without engaging in race, we also cannot understand anti-immigrant movements without engaging in religion.

Irish Catholics and Antebellum Nativism

In the antebellum period, for example, the first major anti-immigrant movement targeted Irish immigrants. Nativists depicted the Irish immigrants as animal-like, poor, drunken, corrupt, and ill-suited to democracy. In particular, nativists considered the Irish dangerous because of their Catholicism. As Samuel Morse argued in 1835, the growing number of foreign-born Catholics threatened to place Americans “into the hands of foreign powers.” As he explained, “Popery is opposed in its very nature to Democratic Republicanism; and it is, therefore, as a political system, as well as religious, opposed to civil and religious liberty, and consequently to our form of government.”

This religious animus found political expression through the Know-Nothing Party, which in 1856 embraced a platform that was not only anti-immigrant, but also explicitly anti-Catholic. In addition to “More stringent & effective Emigration Laws,” the Know-Nothing Party called for “Hostility to all Papal influences, when brought to bear against the Republic” and “The amplest protection to Protestant Interests.”

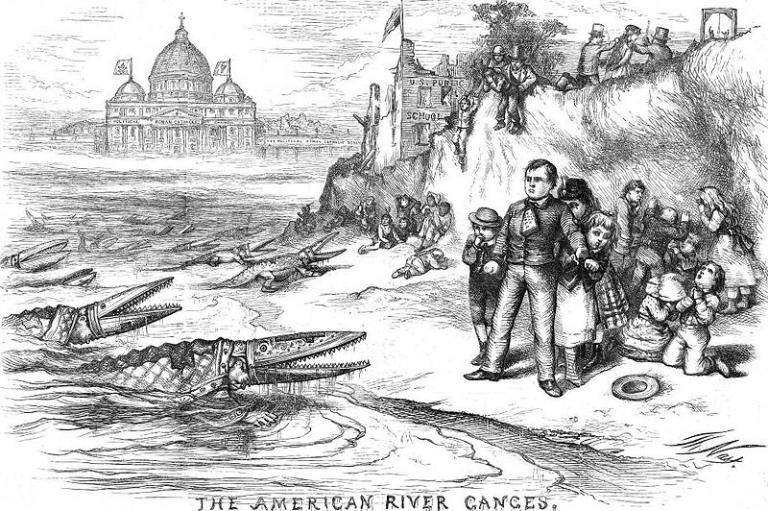

The anti-Catholic dimensions of nineteenth century nativism also found expression in popular culture. In “The American River Ganges,” Thomas Nast famously depicted Catholic clergy as a horde of alligator-like monsters invading American shores, while a Bible-wielding Protestant man attempted to protect the women and children. (President Trump’s rhetoric of immigrants as animals that are infesting the United States clearly has historical precedence.)

Chinese Heathens and the Push for Asian Exclusion

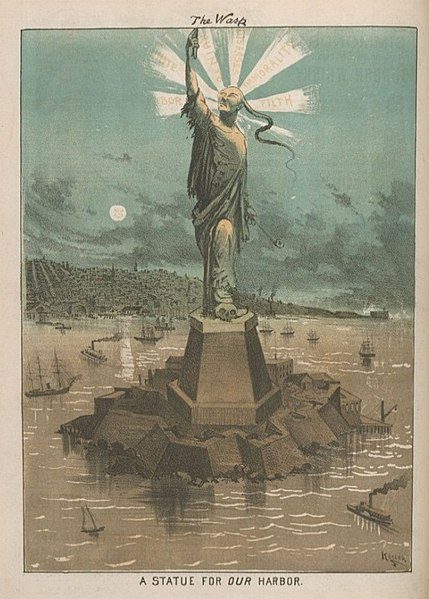

Religious animus shaped immigration policy in the second half of the nineteenth century, particularly during the push for Chinese Exclusion. Supporters of Exclusion argued that Chinese people were slave-like “coolies” who posed a threat to free white labor and were incapable of assimilating into American society. But here, too, religious difference was central to the construction of Chinese people as undesirable migrants. Exclusionists emphasized that Chinese people were vice-ridden “heathens” who endangered America’s white Protestant majority and its morality. As the historian Beth Lew-Williams explained in her new book on Chinese Exclusion, “the term ‘heathen’ was both a racial and religious marker, connoting the pagan, wild, uncivilized, and savage.” The idea that Chinese people were pagan and savage found vivid representation in the political cartoons of the era, particularly in George Keller’s 1881 drawing, “A Statue for Our Harbor.” In it, Keller rendered the Statue of Liberty as a foreboding caricature of a Chinese man, dressed in tattered clothing and illuminated by a halo inscribed with the economic, social, health, and moral threats that exclusionists believed that Chinese people posed to American civilization: “RUIN TO WHITE LABOR,” DISEASES,” “FILTH,” and “IMMORALITY.”

After Chinese Exclusion was enacted and the “Chinese question” appeared settled, American nativists who continued to fear the “Yellow Peril” shifted their focus to immigrants from Japan. At this stage, too, religious hostility continued animate the push for exclusion. As the Asiatic Exclusion League argued in 1911,

These Asiatic immigrants are an unmitigated nuisance in every community in which they have settled…their ways are not as our ways and their gods are not as our God, and never will be. They bring with them a degraded civilization and a debased religion of their own ages older, and to their minds far superior to ours. We look to the future with hope for improvement and strive to uplift our people; they look to the past, believing that perfection was attained by their ancestors centuries before our civilization began and before Jesus brought us the divine message from the Father. They profane this Christian land by erecting here among us their pagan shrines, set up their idols and practice their shocking heathen religious ceremonies…

Racial Nativism, Religious Nativism, and the Johnson-Reed Act

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, the toxic combination of religious hostility and racial animus put many other immigrant groups in the crosshairs of nativists. For example, the Ku Klux Klan, reinvigorated after World War I, targeted their hatred toward not only African Americans and immigrants, but also Catholics and Jews. The intersection of race and religion even shaped the legal reasoning of the period—most notably, in United States v. Baghat Singh Thind. In this 1923 case, the Supreme Court unanimously decided that an Indian-born man was racially ineligible to become a naturalized citizen because he was not “white,” but a member of “Hindu stock.” To be clear, Thind was actually Sikh, not Hindu, but the confused overlap of racial and religious categories indicate that both operated to settle the status of South Asian immigrants as outsiders who were unwelcome and excluded from the American nation.

During this period, racial anxiety moved to the front and center of American nativism. As the historian John Higham explained, “Racial science increasingly intermingled with racial nationalism,” and this new “race-thinking,” which drew from questionable natural and social science, undergirded arguments in favor of more restrictive immigration laws. The most notorious expression of this new racial nativism was in Madison Grant’s 1916 book, The Passing of the Great Race. In it, Grant warned that the “inferior” racial stock of Southern and Eastern Europe could overcome the Nordic race, which he considered to be “the white man par excellence” and the foundation of the American population. For this reason, Grant argued for limits on the immigration of “the weak, the broken, and the mentally crippled of all races drawn from the lowest stratum of the Mediterranean basin and the Balkans, together with hordes of the wretched, submerged populations of the Polish Ghettos.” The culmination of the racial nativism of this era was the 1924 Johnson-Reed Act, which excluded people who were racially ineligible for citizenship (namely, Asians) and also created discriminatory national origins quotas that privileged immigrants from Northern and Western Europe and drastically restricted immigrants from Southern and Eastern Europe.

The arguments that legislators marshalled in support of the Johnson-Reed Act may not have addressed religion as directly and explicitly as in previous moments in nativist history. On its face, Johnson-Reed Act was religiously neutral and based the admission of immigrants on other categories—specifically, race and national origin. In reality, though, the Johnson-Reed Act came to function as a powerful instrument of religious exclusion. It assigned more generous quotas to countries with sizable Protestant populations at the same time that it substantially reduced the number of people who could immigrate from predominantly Catholic, Jewish, and Orthodox countries. In addition, because it excluded any immigrants who were racially ineligible for citizenship, it prevented the arrival of religious groups that had primarily non-white adherents, such as Hindus, Buddhists, Sikhs, and Muslims. It was only after the 1965 Hart-Celler Act, which ended the racist national origins quotas created by the Johnson-Reed Act, that the immigrant population became more racially and religiously diverse. To be sure, the majority of post-1965 immigrants have been Christian. However, there is no doubt that the end of the national origins quotas inaugurated what Diana Eck has described as “a new religious America,” which is “the world’s most religiously diverse nation.”

Religious Hostility and Nativism in the 21st Century

As these examples demonstrate, the desire for religious exclusion, not simply ethnic and racial exclusion, has long been at the center of nativist movements throughout American history. Understanding this fact matters, and not simply for the sake of historical accuracy. More fundamentally, Americans cannot adequately address the present problem of religious hatred without first understanding its entrenched roots and its entwinement with ethnic and racial hatred. Unfortunately, religious hatred has been something of a blind spot for Americans. Perhaps because religious freedom is enshrined in our laws, honored in our national culture, and celebrated in our founding myths, we are inclined to believe that American religious life is defined by tolerance and pluralism. The truth is more complicated and much darker than that, though, and if anything is clear from yesterday’s ruling, it is that Americans need to acknowledge that religious hatred has profoundly shaped who we are as a nation, just as racism has.

Confronting our nation’s history of religious hostility means acknowledging our wrongs, but also—to end on a more hopeful note—finding examples from our past that can help us find a way forward. According to Beth Lew-Williams, American Christians saw Chinese people as idol-worshipping heathens, but Protestant missionaries “advanced the most inclusive vision for Chinese migrants” and some of the most vocal opponents of Chinese Exclusion. In fact, the racial nativist Madison Grant criticized Christianity, as he considered its humanitarian care for the weak to be an obstacle to his vision of a racially pure Nordic nation.

And yet white Protestants today—in particular, lay white evangelicals—are not standing in forceful opposition to contemporary nativism. As the sociologist Janelle Wong recently discovered, white evangelicals are much more conservative on immigration issues compared to their black, Latino, and Asian American counterparts. Importantly, these white evangelicals also feel embattled: half of the white evangelicals who responded to her survey reported experiencing greater levels of discrimination than they believe Muslim Americans face. Given this level of racial and religious resentment, it is perhaps no surprise that 80% percent of white evangelicals voted for Donald Trump in 2016 and that they continue to be consistent supporters of even the most controversial immigration measures of the Trump administration. But a look to the past reveals that there are other political possibilities, and white evangelicals today could choose to follow the example of their Christian predecessors who responded to changing religious and racial demographics with generosity, inclusion, and compassion. Will white evangelicals eventually counter the virulent anti-immigrant politics of our current moment, or will they opt instead to go down the well-trod path of religious and racial nativism? If they choose the latter, they would be continuing a well-established, and ugly, American tradition.