It was a bright, sunny day in King’s Lynn last week. A faint breeze of sea salt, along with the echoing cries of sea gulls, reminded us that this was a port city. Although hidden at first by the twisting streets, the soaring towers of St. Margaret’s church (now King’s Lynn Minster) soon came into view.

This is what I had come to see. The west facade alone made the trip worth it. 12th century stonework intertwines seamlessly with 13th century Early English and late medieval Gothic styles–check out the fifteenth-century perpendicular Gothic window next to the 12th century reed molding. But neither architecture nor the fantastic Saturday market brimming with strawberry cheesecake and pork pies was the reason for my visit. It was because this was the parish church of Margery Kemp

I have written about Margery Kempe several times. A late medieval woman hailing from King’s Lynn, she was a wealthy sometime business owner married to a long-suffering husband and a mother of fourteen children. But if Margery Kempe had a twitter feed, she would not have highlighted any of these in her handle description. She was simply a “creature” of God, dedicated to piety, serving and praying for the world.

One of the many striking aspects about Margery Kempe’s life is her relationship with her husband. Despite being married and a mother of several children, Margery’s role as wife and mother factored little into Margery’s book. Indeed, to modern readers (especially modern evangelicals who are accustomed to identifying women through their roles as wives and mothers), it is often disturbing how little Margery mentions her family. Margery also exerts significant power in her marriage, probably stemming from her class and wealth combined with the considerable force of her personality. She acts independently from her husband and even leaves her husband and family for long periods as she embarks on pilgrimages throughout England and Europe (all the way to the Holy Land). At one point, Margery Kempe even barters with her husband for sexual freedom–promising to pay his economic debts if he will release her body from the marriage debt (sex). He agrees, although he calls her “not a good wife.”

Lately I have been finishing an article (destined for Fall publication) that highlights one of my favorite medieval sermon stories. It was a very popular sermon story repeated in multiple collections. I know it best from the medieval compendium Jacob’s Well. It is about a married woman who defies her husband. Not surprisingly, every time I read it, I can’t help but think about Margery Kempe.

Here is the sermon story (modernized):

A charitable noble woman dedicated herself to serving lepers. She was married to an aristocratic lord, however, who was less charitably inclined. One day when he was out hunting, a leper stumbled up to their gate begging for hospitality. The woman immediately brought him inside her home. She washed his feet and cared for his wounds with her own hands. When he expressed his exhaustion and asked to be allowed to rest for a while, she immediately agreed. But when the leper asked if he could rest in her own bedchamber, the woman paused. She knew how much her husband detested lepers and that he would be angry if she allowed not only another man but a leprous man to sleep in the conjugal bed. She expressed her fears to the leper, exclaiming that her husband “will slay both you and me” if they were found out. The leper persisted that he needed to rest in her own bed, and the woman graciously acquiesced. She opened up the bedroom door and laid the leper down on her own silken sheets.

This is a significant moment in the story.

Married women in late medieval England, just like this noble lady and even like Margery Kempe, lived under the law of coverture. As Cordelia Beattie describes coverture, it is “the common law doctrine which meant wives were under the guardianship of their husband, had no legal possessions of their own, and could not enter into economic contracts in their own name.” Wives in medieval England were under the authority of their husbands–they legally had to submit.

Yet this noble lady defies her husband. Because she has no legal possessions of her own, she is lending the use of her husband’s belongings to take care of the leper. Because her husband had forbidden her to do this, she (technically) is stealing from him.

So, when the husband comes home early from hunting, we understand why the wife is frightened. She tries desperately to keep her husband from entering their bedchamber. Her behavior, of course, only arouses his suspicions and he finally grows so angry that he breaks down the door.

This is the next most significant moment in the story.

When the husband enters the bedchamber, he does not find the leper sleeping in his bed. He finds only a beautiful, clean room with an empty bed and a sweet fragrance “so sweet as if it were paradise” lingering in the air. The leper had miraculously disappeared, leaving no trace of his presence.

Everyone was confused. The husband, confused to find nothing in the bedroom, complements his wife on her housekeeping skills. The wife, confused to not see the leper sleeping in the bed, breaks down and confesses what she has done. Somewhere in the midst of all this confusion, both husband and wife realize they have witnessed a miracle. Most significantly, the husband realizes that he was wrong in his uncharitable behavior. He converts, on the spot, to the faith of his wife.

For medieval Christians, this story was about faith and salvation (in broad brush terms). The woman had the faith to do what God had called her to do. Not only did God bless her for her steadfastness, rescuing her from the angry husband, but her faith also proved the salvation for both herself and her husband. As the story reads, “she and her lord were saved from death to life, from sin to grace, from dread, from sorrow, and from pain to endless joy.”

For medieval Christians, this story was about faith and salvation (in broad brush terms). The woman had the faith to do what God had called her to do. Not only did God bless her for her steadfastness, rescuing her from the angry husband, but her faith also proved the salvation for both herself and her husband. As the story reads, “she and her lord were saved from death to life, from sin to grace, from dread, from sorrow, and from pain to endless joy.”

But the backdrop to the story is marriage. Specifically, the tension between a married woman’s physical and spiritual obligations. Legally women were subject to the authority of their husbands, but spiritually they were under the authority of God. God trumps marriage. The woman not only went against the wishes of her husband, defying him openly, but she was rewarded for doing so. She was in the right; her husband was in the wrong.

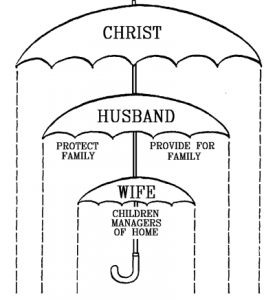

As a Baptist woman once trapped in a complementarian world, I find this fascinating. I remember so many sermons and lessons (some just a scant three years a go, others as far back as 25 or 30 years ago) about the divine family hierarchy–God, husband, wife. Yet, in this medieval sermon, the woman owed allegiance to God over her husband. She didn’t need special permission from her pastor or older woman mentor to allow her to defy her husband. She simp

go, others as far back as 25 or 30 years ago) about the divine family hierarchy–God, husband, wife. Yet, in this medieval sermon, the woman owed allegiance to God over her husband. She didn’t need special permission from her pastor or older woman mentor to allow her to defy her husband. She simp ly decided to obey God rather than her husband, and God approved of her choice. Indeed, one could argue that the angel/leper was intentionally provoking the woman to disobey her husband. He asked for all the things that the husband had forbidden. Was this simply a lesson for the husband? Teaching him to forgo his pride and obey God’s commands to care for those in need? Was it simply a picture of God using the “weak things of this world” to shame the strong? Or was it a more broadly applicable lesson? That God’s ways are not man’s ways (and I intentionally used ‘man’ instead of ‘human’….); that man-made laws (again intentional), especially those emphasizing female subordination, are not always correct; that women, in God’s world, are free?

ly decided to obey God rather than her husband, and God approved of her choice. Indeed, one could argue that the angel/leper was intentionally provoking the woman to disobey her husband. He asked for all the things that the husband had forbidden. Was this simply a lesson for the husband? Teaching him to forgo his pride and obey God’s commands to care for those in need? Was it simply a picture of God using the “weak things of this world” to shame the strong? Or was it a more broadly applicable lesson? That God’s ways are not man’s ways (and I intentionally used ‘man’ instead of ‘human’….); that man-made laws (again intentional), especially those emphasizing female subordination, are not always correct; that women, in God’s world, are free?

Lately, historians have begun to argue that scholars have over focused on the strictures of coverture for medieval women. Yes, coverture was the law and “remained a key feature of the law in northwest Europe”. But it didn’t bind medieval women as absolutely as we once thought. Despite being married and not legally able to stand in court without their husbands, some wives did represent themselves in court and even paid their own fines. Married women, in some places, could be active in their own legal interests without needing to defer to their husbands. Some manorial courts completely ignored laws of coverture, dealing with women as individuals. Margery Kempe is a prime example of a married woman who lived rather free from the bonds of coverture.

Coverture, in other words, was flexible. Apparently, at least for the noble woman in the sermon story, so was submission.

Just something to think about.

(all images, excluding the umbrella, from my recent trip to King’s Lynn and St. Margaret’s)