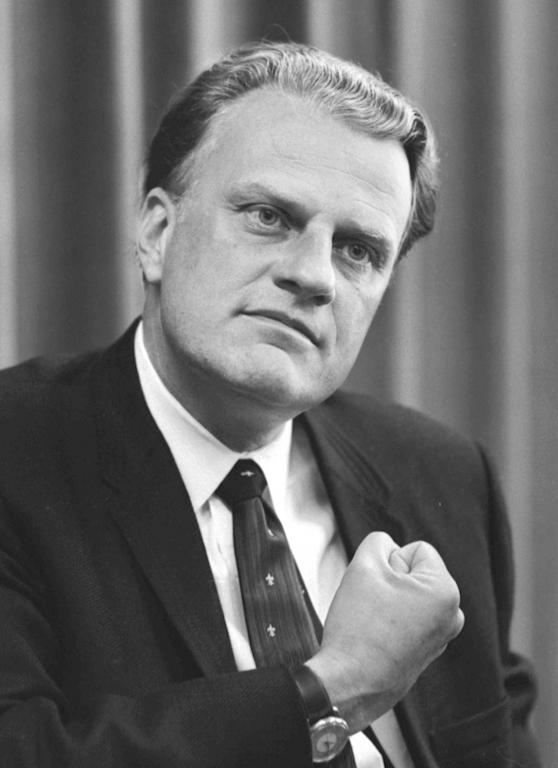

For many decades, it was easy to forget the fiery, apocalyptic Billy Graham. We heard him voicing gentle invitations to experience God’s love at evangelistic meetings. Or we saw him promoting détente with the Soviet Union in the 1980s. Or we cringed, when as an old man, he was used by his son Franklin Graham to fuel right-wing politics.

But these are sanitized Grahams. He also had a fire-breathing apocalyptic side to him. He spoke with tremendous force as a young preacher. In addition to Hope for Each Day: Words of Wisdom and Faith (2002), he wrote Storm Warning: Whether Global Recession, Terrorist Threats, or Devastating Natural Disasters, These Ominous Shadows Must Bring Us Back to the Gospel (1992). Graham also expressed anti-Semitic views to Richard Nixon in the Oval Office. “They’re the ones putting out the pornographic stuff,” he explained to the president. The Jewish “stranglehold has got to be broken or the country’s going down the drain.” In an even more excruciating statement found in just-released tapes, Graham continued, “The Bible talks about two kinds of Jews. One is called the synagogue of Satan.”

This kind of language was not new in 1970s evangelicalism. Certain sectors of fundamentalists had long scapegoated Jews (even as they supported the State of Israel). Nearly all believed that civilization was cracking, that the end of the world was imminent.

And it wasn’t just Graham. His wife Ruth also grew up with the apocalyptic ethos of twentieth-century fundamentalism. One of the best anecdotes in Matt Sutton’s superb book American Apocalypse (2014) features her at a missionary boarding school in Pyongyang, Korea. In 1933 Ruth had written her father, missionary doctor L. Nelson Bell, in China. In the letter she described blurting out to a classmate, “Oh, just think, the end of the world may come soon and then we will be so happy.” Her roommate responded, “Oh you Bell girls . . . surely are stuck on the end of the world.”

As Sutton so aptly puts it, “Both Ruth, who would grow up to marry evangelist Billy Graham, and Nelson, who would become one of the primary architects of modern American evangelicalism, were indeed ‘stuck’ on the end of the world. And they were not alone. In the 1920s and 1930s, American fundamentalists—at home and abroad—felt a new sense of urgency. For generations they had been carefully combing both their Bibles and their daily newspapers for evidence that Jesus’s return to earth was nearing.”

Consider the shocking developments of the times. Mussolini was trying to restore the Roman Empire. Hitler was driving Jews out of Europe. Stalin was institutionalizing state atheism. There was a global economic depression. As Sutton characterized the mood, “The countdown to Armageddon had begun.” To be sure, no single fundamentalist predicted all of these developments. But collectively, fundamentalists had. And besides, Sutton writes, “Global events in the 1930s so closely paralleled their long-held predictions that they spent little time fretting about past prophetic mistakes.”

This continued, of course, in the Cold War. Billy Graham’s career coincided with the first frightening years of anxiety over Soviet aggression, and his fire-breathing sermons implicated all sorts of global movements and events. It was a cultural and political moment that encouraged an embattled, apocalyptic posture.

At a 1947 “Christ for This Crisis” crusade in Charlotte, North Carolina, Graham preached the following sermons: “The End of the World” and “Will God Spare America?” He declared that communism was “Satan’s religion,” a “great anti-Christian movement.” In 1952 Graham mailed the book Communism and Christ to every member of Congress and the presidential cabinet. Communism, it delineated, had its very own trinity: “Marx the Lawgiver, Lenin the Incarnate Truth, Stalin the Guide and Comforter.” At a 1954 crusade in London, Graham distributed calendars that read, “What Hitler’s bombs could not do, socialism with its accompanying evils shortly accomplished.” He later said it was a misprint—that it should have read “secularism—but the text did reflect accurately the evangelist’s dualistic sensibilities.

Graham, according to biographer Steven Miller, was “the quintessential Cold War revivalist. From the very beginning of postwar tensions with the Soviet Union, he linked his evangelism to the destiny of the United States and its leaders.” He was a product of his times. Fundamentalist theology combined with the brutalities and anxieties of World War II and the Cold War, perhaps making it only natural for him to scapegoat Jews in sycophantic conversations with the most powerful man in the world.

As reports surface of California banning the Bible and of this week’s White House dinner for court evangelicals, it appears that fundamentalism and evangelicalism may feature more continuity than discontinuity. History may not repeat itself (Obama is not FDR, and 9/11 is not the Cold War), but it surely rhymes.